ELIZABETH R. CURRY POETRY CONTEST WINNERS

Winner:

Lucian C. Mattison for “Yet”

Runner-Up:

Mary Liza Hartong for “Ruby Slippery”

FICTION

Fever

Bim Angst

Jimmy’s Playroom

Jenny McBride

The Dilemma

Karen Fayeth

Now You See Me

Haylie Smart

Putting Mom Back Together Again

Theresa Taylor

A Foregone Conclusion

Jonah Smith-Bartlett

POETRY

Casting Light

F. Patrick Stehno

Feeling as Alone as the One Finger I Showed Him

Robert Rice

A Thousand Wildfires

Sierra Windham

I Have Not Forgotten

Bleuzette La Feir

Oil on Linen

Benjamin Nardolilli

3 AM

Susan Flynn

Two Voices: A Few Small Nips

Carolyn Kreiter-Foronda

My Last Husband

Jodi Adamson

For all the other dances, I was perfect

Judith Arcana

Fifteen

Kristen Jackson

On Seeing, Too Close

Mary Catherine Harper

The Van Gogh Collection

Paula Brancato

Aphorisms for a New Science

John Urban

Genealogy Homework

Sharon Kennedy-Nolle

Freedom

Holly Day

Summer Simplicity

Judith Grissmer

How to Sample a Sound Bite

Frank C. Modica

About Fireflies

Susan Flynn

CREATIVE NONFICTION

smaller

Zinnia Smith

For Each Pilgrim Two Tales

Darren DeFrain

39 Things People With Anxiety Want You to Know

Michael William Palmer

Swarming

Shilo Niziolek

(Nonna, 2016)

Amanda Salvia

Queens of Slippery Rock

Anna Swartwout

Brenna Waugaman

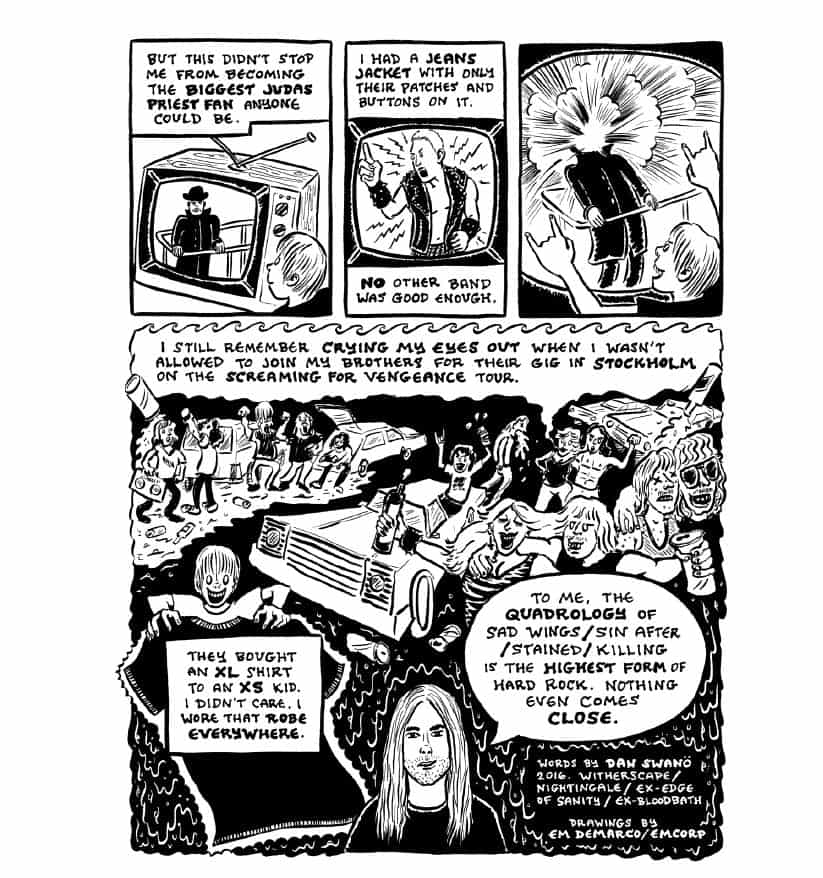

TEXT & IMAGE

One Day in the Late ‘70s

Em DeMarco

ELIZABETH R. CURRY POETRY CONTEST WINNERS

Winner

Lucian C. Mattison

Yet

After Mohamad

You lived happily. The rocket

struck the wall like a hammer of lilies.

Colored cloth tied to the barrels

of rifles fluttered as if waking the wind

to itself. Night shelling was a game

of hide-and-go-seek in the movie theater

basement, and the next day, they

mourned the found with pictures of

their unfound faces, a parade of opposition

colors, more banners and songs

to buoy the air. Many left, you

among them, to live absent

of conditioned fear, a parallel life.

Makdissi continued to follow Hamra,

demonstrations ushered the trucks

of soldiers—emptied and filled like beer

glasses on the bar. Nationalist of the present

tense, blinded augur, you wish

for nothing more than the chance

to draw lines around happiness

again: bouquet of childhood, petals

like ticker tape, wind carrying you

like prayers to a neighbor’s window.

Runner-Up

Mary Liza Hartong

Ruby Slippery

The scarecrow wants a brain.

The tin man wants a heart.

The witch just wants a pair of shoes

which, if you ask me, only proves

that women are not frivolous

but learn to want less from the start.

POETRY

Michelle Kubilis

Kampala

there is no place to hold hands but in bed

please forgive me for that

for valentines day you wanted lions

uganda beckoned a business trip

at check in we said our company

demanded we save money each day we

pulled back both covers lounging

please just let us hold hands wed know

if amin did that to his bishop

can you imagine what theyd do to fag

Sierra Windham

I Thought I Found a Home in You

Your honeysuckle tongue

has all the backlash

of a whip, and I’ve been trying

to hold your hand

but your words leave

welts on my skin.

I settled for silence

but all that remained

were the fumes

from your pretty cherub

mouth; (toxic)

you watched

as my body rotted

from the inside out

and buried me

beneath the floorboards of our

broken house

(you are so toxic).

You said you wanted a home

but my feet were cold

before I even crossed the threshold.

Eric Pankey

To Formulate a Definition

How often we are drawn together

By a single act of carelessness

The false positive or double negative

Understood as its opposite

We smear ourselves with ash

To make of the self a void

But instead of disappearing

We leave footprints behind

On the kitchen’s slate floor

The coastline cliffs collapse

Loose threads of rain

Unravel from a cloud sampler

But what is the proximate cause

We learn to discern patterns

And predict the vernal equinox

We hold a curve of willow charcoal

And make a hesitant first mark

Then write a treatise on the nature of things

FICTION

Haylie Smart

Now You See Me

“What is it?” Mr. Snell said. He rose from behind his desk and peered down at the piece of paper through his wire-rimmed glasses. “It’s a note,” Ms. Reece said. “I just found it on her keyboard. What do you think it means?” Mr. Snell sighed. “I’m not sure, but I’ll give her family a call and see if they have an idea of where she’s at or if it has anything to do with what happened.” Ms. Reece frowned, a deep wrinkle of concern creasing her forehead. “Just go and sub her classes today until we get this figured out,” Mr. Snell said, dropping the paper on his desk. Ms. Reece shook her head and placed trembling, wrinkled fingers over her mouth. “I just can’t believe it. Why would someone do something like this?” Rubbing a hand over his defeated and exhausted face, Mr. Snell shrugged and read the letter again: Now you see me.

TWO DAYS EARLIER

Diane seethed when she read the group email, her red nails drumming on the desk. This was the last straw. We missed the birthday luncheon last month because of state testing, and other things, so how about we get together tomorrow during our plan period to celebrate the remaining birthdays and Laura’s going away for maternity leave? What sounds good to eat? —Molly

“‘And other things’ my ass,” Diane groaned. She reached for a dark curl near her cheek and twirled it around her index finger until taunt, a nervous habit she couldn’t break.

Since the beginning of the school year, every month the English and Special Ed. departments gathered together for a birthday luncheon. They were meant to celebrate the birthdays for that month. If there was a month that did not have any birthdays, then it was decided to celebrate June birthdays, since school was not in session. And on the next “no-birthdays month” they would celebrate July.

There were no April birthdays, so Diane was next having the only July birthday, but other things had kept them from getting together. There were two May birthdays, so now Diane would be grouped in with Brittany and Emma. To make it worse, they were also celebrating Laura’s maternity leave.

Diane didn’t believe in coincidences.

It was always up to the birthday person what kind of food they would eat at the luncheon and Diane fumed when Ashlee replied, It better be Mexican. Ashlee, with her brisk stride and nose always pointed up as if she were a coonhound in hot pursuit, had already celebrated her birthday in November, and somehow still managed to get away with whatever she wanted. It was then decided, of course: Mexican.

A sour taste rose in Diane’s mouth as she replied through gritted teeth, I’ll bring mango salsa.

Later that night as Diane diced tomatoes, onions, peppers, and mangoes she wondered why she went to the luncheons in the first place. She could easily make an excuse for why she couldn’t make it: a parent-teacher conference, preparation for the next day’s lesson, or research for future lesson plan ideas.

But she never did.

Maybe because she still had a sliver of hope. But the truth was they didn’t care if she was there or not. Diane’s mind drifted back over the last nine months as the new teacher at Winston Hughes Middle School. It was Diane’s first year teaching and ironically, she ended up at the same middle school she’d attended fourteen years earlier. Everything was different. Beige walls were now covered with brightly colored murals depicting quotes about respect and the joys of school life, famous writers and scientists, and, of course, the school mascot: zebras. In other areas of the school, vibrant mosaic artwork stretched down the halls from floor to ceiling. Millions of small broken pieces of glass and stone created the most beautiful scenery. This display of intricate creativity sparked a fire inside Diane. She was already passionate about learning and couldn’t wait to pass on that same joy to her students. Knowing teaching was her calling, she bounded in with her red lips glowing and short, dark curls bouncing. She believed in growing where she was planted. But the one thing that was most different from the school she remembered were the teachers. Or maybe they were exactly the same, but she was blinded by her insignificant and selfish thirteen-year-old problems. As Diane rushed to and from the teachers’ workroom in preparation for the first day, the other teachers didn’t have the same bounce in their step as she did. Shuffling along, with a soft swish, swish of their dragging feet, their eyes were glassy and distant. Not making eye contact when passing each other in the hall, Diane chalked it up to the disappointment of summer being over and having to start a new routine. But as the months went on, the dreary-eyed stares continued. Their pasty skin, disheveled clothes, and messy hair blended in with their drab and disorganized classrooms. Diane, with her satin blouses and pencil skirts, stood out like a throbbing, red thumb. Even the cheerleading coach, with her bleached hair chopped at the chin, wore a permanent frown to match her dead brown eyes. Her name was Joy. Maybe they thought the mural paintings and mosaic artwork would trick parents into believing this was a school that cared. A school that could make a difference. Diane decided it was where teachers went to die. The hospice of schools. But, nonetheless, Diane would make the best of it, as she always did. She couldn’t have known though she was in for a rude awakening. From day one, Diane was rejected by her department, for reasons she would never learn. The first day of school had just ended and the halls were cleared, except for broken pencils, gum wrappers, and crumpled notebook paper that always decorated the tiled floor. She heard an approaching group of voices outside her classroom door. “We’re going to try that new Cajun restaurant in town tonight. It’s got great reviews on Yelp.” Diane recognized the voice. It was Luc, the sexy history teacher down the hall. If there was anyone who didn’t belong in the school, it was him. With his bright sapphire eyes and cheery attitude, it was a mystery the other teachers hadn’t leeched it out of him in his three years there. He wasn’t married, and the disappointment among the single teachers spread like the plague when they found out he was in a serious relationship. Diane, wanting to fit in like any new teacher, joined the group of seven or so in the hall to contribute to the meaningless conversation. “Oh, you’ll love it,” Emma gushed. A round woman, she was married with three kids, but every time Luc passed her classroom she beamed at him like a puppy staring expectantly at a tennis ball. This perplexed Diane because the woman was notoriously known as an “unsmiley” person. “John and I went last week. You have to try the spicy gumbo.” There was a moment of silence as Luc smiled at this comment. Diane jumped in.

“Where is this place at? I love Cajun fo—” “So tell us Luc, when are you going to pop the question?” Molly interrupted, snuffing out Diane’s two cents. As the head of the English department, Molly reminded Diane of a sloth. Not only was she glacially slow, but she wore a thin, creepy grin at all times. No one glanced at Diane. Just then, the group of people shifted their bodies into a loose circle, facing their backs outward. They all met each other’s gazes and continued their conversation with an unsettling ease. They had done this before. Diane was not naive. She was the outsider and not welcomed. She retreated to her classroom and gathered her purse and lunchbox and left. Never known to be a quitter, Diane attempted to join the hallway conversations day after day, before and after school, but each time ended with the same blatant rejection. During lunch, she joined the English teachers in Molly’s classroom, the only place they ever ate lunch, and took her place among them. “Did you have Andrew Slicks last year, Brittany?” Emma asked. “That kid doesn’t have a clue. We’re doing a research project over the 1960s, and when I gave them a list of different topics they could use, he asked why 9/11 wasn’t on the list.” All the women burst into laughter. “I tell you, these kids are getting dumber every year,” Brittany agreed. The women paused to take bites of their lunches. This was Diane’s chance.

“I understand if he got the decade off, but he wasn’t even in the right century.” Diane laughed at her joke, hoping to evoke more laughter from the women. Ashlee coughed into her chubby hand, Emma stared at her cell phone, and Mary read an email on her computer. Right then, Laura waddled in with her lunch tray, looking seven months pregnant though she was only four months along. Her bright red curly hair bobbed along with each shuffle. “I swear the boys are fighting today. They’ve just been kicking at each other all morning.” The women laughed again and started sharing similar pregnancy stories. Am I fucking invisible? Diane thought. If I stood and screamed, would they even look up? Without finishing her lunch, she threw it away and left the room in silence. This became their norm. Every day, they sat scattered in Molly’s classroom eating their lunches and talking about school politics, Laura’s growing belly, their friends’ Facebook posts, or stories about their students’ stupidity. Not wanting to be known as the teacher who eats alone in her classroom, Diane sat at the edge of the group, eating in silence, and just listened. She had made several attempts to join in the conversations, but with each disregard to her contribution, Diane grew more and more silent. She wasn’t sure when she quit talking altogether. The worst part about all of it was Emma was Diane’s mentor, the veteran teacher who was to offer guidance and help with lessons to a new teacher. Diane remembered the first time she wandered into Emma’s classroom. She was in need of advice on how to effectively deliver that day’s lesson that had been assigned to her. Startled, Emma looked up from her cell phone and looked at Diane with curious eyes, as if she were seeing her for the first time. A stranger who had somehow become lost in a school and was in need of assistance on how to find their way out. When it registered what Diane was asking, her brown eyes dimmed and she dismissively waved a hand. “I don’t care. Do what you want,” she said before looking back at her phone. Do what she wanted? Diane was a brand new teacher. She didn’t know what she wanted to do. She didn’t even know what she needed to do. Confused, Diane retreated to her classroom and hoped Google would answer her question. It was a Tuesday morning in late February, before school started, when Diane realized she was staring at a Skittles wrapper on her classroom floor. She wasn’t even thinking of anything. Just sitting there and staring. Waiting for the bell to ring. The understanding slapped her rigid. She had become those bleary-eyed teachers waiting for death. This knowledge devastated her to the center of her being. All she had ever dreamed of was suddenly a toxic wasteland. Diane cupped her face in her hands and wept. She racked her brain for anything she might have possibly done to deserve such cold and unwelcoming coworkers. They were quite different. She was much younger than them, slimmer, unmarried, and without children. Did they see her as a threat? Beneath them? Had all the teachers once been like her, but years of neglect turned them into bitter old hags?

Diane decided then she would make it until the end of the school year and look for another job. She would not die there. But then the email came. Her birthday was intentionally skipped. By grouping hers in with the others and a maternity farewell party, it would be ignored entirely. That was it. She wouldn’t stand by idly any longer. After slicing up all the vegetables and mangoes and adding spices, lime juice, and a little sugar, she knew what the last ingredient needed to be. Whistling “Tiptoe Through the Tulips,” a tune her mother taught her, she mixed in a large amount of thallium powder into the salsa. The key ingredient in rat poisoning, “The Poisoner’s Poison” was tasteless and odorless. She had asked a friend where to buy some, making up a story about having a mice problem. The best aspect of thallium is that it killed slowly. Beginning with vomiting, nausea, and diarrhea, it then progressed into nervous system damage, loss of reflexes, convulsions, and eventually death. It’s possible it would appear they were just sick and couldn’t recover. Satisfied with her work, she covered the salsa and placed it into the fridge. “I will not die there,” Diane hissed.

As Diane took her seat at the far end of the table in Molly’s room, she watched the women pile food onto their plates at the buffet table and seat themselves. Diane had been first to make her plate because she needed to appear to eat and then excuse herself early. She’d make up a story, telling them she had to call a parent about their child’s missing assignments. Having no appetite, Diane took small bites of Spanish rice and chips and queso. “Mmm, this mango salsa is awesome. Who made it?” Samantha asked, a Special Ed. teacher who only came around at the luncheons. All the women mumbled they didn’t know, but agreed it was homemade. Diane watched them cram their faces with silent satisfaction and after she felt content with the amount they were eating, she excused herself and retreated to her classroom. No one looked up. After scribbling a note on a piece of notebook paper, Diane grabbed her purse and a few personal items, stuffing them into a large Target plastic bag. She laid the note on her keyboard and breezed out of the school. With her head held high and red lips curled into a sneer, Diane’s black high heels clicked on the ground all the way to her car.

Jonah Smith-Bartlett

A Foregone Conclusion

My father insisted that I attend Saint Joseph’s College in Rensselaer, Indiana because it was once the school of Gil Hodges, his third-favorite ballplayer of all time and his absolute favorite first baseman.

By my sophomore year, I surrendered to the fact that I would not become a close friend to a future Hall of Fame Gold Glover, but instead a favorite project of the priests that roamed the campus like rabid squirrels, ready to bite the underclassmen with a stinging shot of holiness. “Clarence Richards!” they would call out to me, breaking prayerful silence or psalmic utterances, hoping, I assumed, that this would be the day of penitence for the boy of academic mediocrity but alcoholic exceptionalism. I was just as amazed as they were, if not more, when I noticed exactly how fast my short legs could take me.

For those men who had dedicated themselves to lives of celibacy, I was frankly surprised and somewhat disappointed at how soon, certainly by my junior year, they had deemed me a lost cause for Saint Jude. The exception was wiry Father Anthony, who daily left a new volume of rigid theology outside my dormitory door. The most memorable of these— that is, the one that I recall now, twenty-two years later— was The Precious Blood: The Price of Our Salvation by Frederick William Faber. Within this thick book, Father Anthony underlined a number of paragraphs with light pencil marks. An example of Faber’s work (and I can’t imagine that this Frederick William Faber was a joy to be around in any social setting) was:

Alas! We have felt the weightiness of sin, and know that there is nothing like it. Life has brought many sorrows to us, and many fears. Our hearts have ached a thousand times. Tears have flowed. Sleep has fled. Food has been nauseous to us, even when our weakness craved for it. But never have we felt anything like the dead weight of a mortal sin. Later I would learn that Faber wasn’t wholly isolated by his theological rigidity. He did occasionally speak quite plainly. “Every moment of resistance to temptation,” he wrote, “is a victory.” By the beginning of senior year, almost all students at Saint Joseph’s had resigned themselves to the idea that free will, had it ever existed at all, was now certainly over. Their character (and the content of this character would determine the content of their future) was cemented in the choices of the previous three years. The boys with the wire-rimmed glasses and briefcases who fancied themselves the head of the student body politic were on their way to city halls and state legislatures. The philosophy majors, many of whom were poetry minors, were off to compose the elegies of young hopes of financial success. The artists would starve by passion, and the writers by the lack of the right word. And the education and the business majors who had thus far managed to avoid much ambition at all would do just fine. Those who lacked a vision for their future as graduation loomed large (and I was in this repellant bunch) twiddled thumbs, loosened belts, said things like, “Smoke ’em if you got ’em,” and “See you in the Funnies,” and wrapped pillows around their heads so as not to hear the noise of the alarm clock at their bedside. Saint Joseph’s, now including even Father Anthony, was ready to get rid of me. Yet, despite full academic satiation, I found myself hungry. My stomach grumbled even after a large meal and my mind raced late into the night, causing a sleeplessness that made my whole body ache throughout the next day. I was sore because, really unbeknownst to me, I had been straining since I first stepped foot onto that campus. I felt like an old horse still forced to pull a carriage—some unjust treachery soon to break me in two. I couldn’t explain it until I remembered Frederick William Faber’s tamer words: “Every moment of resistance to temptation is a victory.” I had resisted for nearly four years. What it was that I resisted wasn’t immediately clear. By temptation, I figured, Frederick William Faber meant vice, if not outright sin, and I had successfully indulged in my fair share of vices. The summation of my years at Saint Joseph’s was one temptation after the next, a series of trials down paths of gluttony and lust. These were only two of the seven deadly sins. To me, the ratio was rather admirable. In this game I was hitting .285, just slightly above the lifetime .270 batting average of the great Gil Hodges.

“Brother Clarence!” Nicholas Galloway called to me from the porch of the apartment that he shared with two farmer boys from just a few miles up the road. His hair was slicked back with Vaseline and he wore a short-sleeved button-down shirt with a thin, light-blue tie. His reputation on campus was unrivaled in its undergraduate magnitude, but the esteem awarded to that reputation shifted dramatically depending on the narrator. For those who spoke highly of Nicholas Galloway, they would note that he had a fine taste in expensive bourbon, excavated well-buried humor from tragic global news stories, and played violin. Those who spoke ill of him would note with disgust his indiscriminate licentiousness. Nicholas was glad to have this be the topic of dining hall conversation. How much they cared made him laugh. “Hi, Nicholas,” I said with some formality. We shared a couple classes. I knew the reputation well, but not the boy. “I was watching you walk this way,” he said. “Thought you would be headed home, but you came this way and here you are. You looked like your head was in the clouds. What were you thinking about?” I was thinking about a hunger, a sleeplessness, and a strain. None of these was I any more willing to share with him than with Father Anthony. “Graduation is just two months away,” I said. For seniors, this was the most innocuous of conversations. We held in common that sense of impending fear, even more than the usual commentary on the weather. “And the great wide world out there,” Galloway said. “Any idea what you are going to do when you are set loose out there?”

“No. What about you?” “No,” he said, running his fingers down the thin blue tie, trying to rid it of wrinkles that were never there. “But I’ve found that the worry does very little good. Well, actually, no good at all. So I’ve given up on worry, not that that stranglehold wasn’t a hell of a hard thing to wrestle away. It’s been instilled in me by a couple of hard-nosed parents who wouldn’t let me near the busy streets until I was well past ten years old. Well, I don’t know what’s going to happen, and neither do you. When you accept that, this warm feeling grows in your gut. It’s hot chocolate on Christmas morning before any of the presents are opened. Or when the bell would ring after gym class. Do you know what I mean?” “Sure,” I said. “The great escape.” “No, not escape,” Nicholas Galloway said. “Liberation.” I spent many nights in his bed. For a week I crawled through his window, worried about what the farmer boys would think. Nicholas encouraged me to take even the smallest dose of bravery and I began to use the front door. He laughed at my anxiety, what I considered to be a brave dive into the deep unknown. Nicholas conjured up memories, earlier realizations. That boy whose assigned seat I always stole in a middle school history class. I called it a practical joke. In some ways it was, I suppose, though I was the mark. A friend’s older brother who boasted by using his broad shoulders and thick arms to lift cinder blocks above his head. A swimming coach. A movie star. A Language Arts teacher who tried again and again to explain the profound need of Odysseus to make his way home. Why home, I thought, when adventure was abounding outside those cavernous Greek walls where Penelope wept? This seemed to be it. The hunger beginning, at least, to be satisfied. I must admit that I was surprised when the whole world didn’t shift. There was nothing dramatic. It was just as if I had been looking at a simple multiple choice question for my entire life, and during one of those nights with that strange bedfellow, I finally realized that the answer was “all of the above.” I awkwardly searched his manhood for my own. That’s what it was at the end of the day. I figured him to be my biographer, revealing to me short but poignant chapters that I never knew were there. I fumbled to read them when he turned off the small lamp on the nightstand. I find it trite now, but up until the point when I fell into the world of Nicholas Galloway, I hadn’t known pleasure, just contentment. My bodily pain now, or most of it at least, was a result of immature ecstasy. And best of all, he played the violin for me. Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto.

Then, drunk on whatever concoction this was, I asked him, “Do you love me?” “No,” Nicholas Galloway said. “Not yet.” And that word—yet—could have offered hope. Though I didn’t tie myself to it. I wasn’t bound to it. What would be the purpose? It was the opposite of liberation. So instead, certainly doomed by that word, I threw the rope above those vowels and hung myself. We walked the stage, took the diploma, and shook the hands of unfamiliar administrators. Pomp and Circumstance and we were gone.

I sat in the dentist’s office and pondered my choices. Home and Garden. The New Yorker. Popular Mechanics. For years the door of the bistro that I managed was thoroughly stuck. It took all the power I had in both arms to open it up and get a whiff of what had been voted online as the best tomato soup in town. A new and overly enthusiastic employee took oil to the hinges. That morning I pulled again with all my might. The door, now good and loose, swung widely and caught me directly in the face. I chipped a top right incisor. Now here I was waiting for a Dr. Prescott, D.D.S., who was on the ninetieth minute of his hour lunch break.

Knowing nothing about growing tomatoes and caring little for a three-page debate on the best domestically made riding lawnmowers, I opted for The New Yorker. A cartoon of President Obama made the cover, running in the direction of the White House and away from a stampede of red, zealous Republican elephants. I skimmed through the black-and-white cartoons inside the magazine—talking dogs in offices, alligators at an airport gate, and an elderly couple siting at a breakfast table and arguing over a newspaper headline. Something about Medicare. Frankly, I didn’t understand a single one. One article after another written for the Sunday brunch mimosa-sipping elites. There was nothing that interested me enough to distract me from the pain of the chipped tooth. I ran my tongue across it. It was sharp enough to not try that again, a blade protecting the vulnerable nerve. Then, nearly putting the magazine down to instead close my eyes and nap until the young assistant behind the desk awoke me, I stumbled across a short story. “A Coward and a Quiet Boy” by one Mr. Nicholas Galloway.

And here some excerpts: “The most remarkable quality about Stephen was the weakness in his wrists. He couldn’t pull himself up to who he ought to be. He couldn’t lower himself down to who he actually was.” It became very clear, and I suppose that I appreciated the most minor favor of a pseudonym, that I was Stephen. “For the third night in a row, I awoke to find him, this time dressed in a thoroughly wrinkled olive-green suit, crawling through my window. He tumbled onto the floor and tried to gather together his dignity before whispering my name. ‘Nicky!’” I never once called him “Nicky.” “Stephen saw a glowing dot on the horizon, and when squinting, he realized that ever-so-slowly it drew closer. It could have been the bourbon that he took from my desk drawer that persuaded him of a grand illusion. This was the judgement of God on its way. None of his studies had prepared for him the inevitable end. None of his whispers, those few whispers of truth, protected him. The priests didn’t know who he became when he loosened his belt. Neither did his parents. Neither did his professors, his classmates, or that small handful of misfit friends. He had confessed only to me and refused to confess to Him. Well, He knew what happened when those spring nights swallowed Stephen up with their steadfast intention to induce sweat by one way or another. He knew.” The conclusion came when Nicky left Stephen to endure his unsympathetic self-affliction. Nicky moved east, and Stephen, in that allusion to tragedy, limped westward. Very precise adjectives and verbs generous to the author, if not authentic, made Nicholas Galloway’s choice in that final paragraph to be inarguably valiant. The author Nicholas Galloway, stated a short, italicized paragraph not long after Stephen’s betrayal, was an author-in-residence at Collins College in the Berkshires.

I drove toward the Green Mountains in a Jeep that was new to the Avis car rental lot. Two days before I chipped my tooth on the door of the bistro, my Ford Taurus had blown a gasket near my favorite record store and was now locked up until further notice at Hal’s Auto Shop. Inside the Jeep I felt bold (as opposed to the Taurus, where I felt safe) and rolled down the driver’s side window to smell all the potent scents of farmland. Soon I found myself twenty-four miles above the speed limit with a radio station playing the anarchic chords of the MC5. Collins College was only an hour further north. My anger felt playful in a strange way, in the same manner, I assumed, as it would set upon a fueled-up boxer in his corner just before the bell rings.

The student behind the welcome desk in the main hall of Collins College was thick in body, hair, and odor, and wore a dark-gray knit cap. It wasn’t hard to imagine him working down at the docks in a Baltimore or even a Gulfport, Mississippi. I approached with some hesitancy only to find him as friendly as he could possibly be. His name was Benjamin, he was from Bangor, Maine, and he was an American History major. I hadn’t inquired about any of these and realized, I suppose, that the long hours at the Collins College welcome desk (situated, Benjamin mentioned as well, at the further point on campus from the Student Center) might make any mighty longshoreman ready for kind companionship. I saw to use his kind and certainly loquacious nature to my advantage. With no hesitancy or ask for identification, he personally walked me up two sets of stairs and down two hallways until we both stood outside the office door of Professor Galloway. His task completed, Benjamin gave me a hearty pat on the back and returned to his lonely, ground-level watchtower. Nicholas did not recognize me when he answered the door, but due to what I assume was a sense of faint familiarity, he invited me inside. A young, long-legged woman sat on a leather couch to the right of his desk. Her blonde hair fit her well, despite being cut with a sure vision but no real plan of execution. She offered a wide smile. It was warm as well. She was a beauty. Not a leading lady of the silver screen, to be truthful, but one with a real shot at modeling blouses in a JC Penny catalog.

“Have a seat,” Nicholas said with such earnestness that I refrained from clocking him immediately. “So, I suppose I might have missed it, so please remind me. Could you give me your name again?” “I never gave it,” I said. I was tempted to say “Stephen.” “Oh,” Nicholas said, turning to the woman on the couch who then smiled at him as widely and warmly as she smiled at me. “Well then, might I impose upon you my own introduction? My name is Nicholas Galloway.” “I know,” I replied, trying to summon up a smile of my own. Given the circumstances I would settle for sardonic.

“I’m a fan.” “Oh,” Nicholas said with surprise. It felt good to know that this surprised him. “Welcome then! How can I help?” I had a hundred answers to this question and not just the ones that I had concocted in the Jeep as I passed one tiny New England clapboard town after another. They ranged back decades and they haunted me even now. I realized in that tiny professorial office, more times than I would have liked to admit. How could he help? It seemed like the answer was, in every possible way. And although he hadn’t helped, although he had abandoned me to a long, lonely, and wicked road of self-discovery, although he had revealed a naked chapter of that self-discovery (and a chapter, mind you, better left in the past) in The New Yorker that I found at the office of Dr. Prescott, D.D.S., as I looked across that desk to faint familiarity beneath fatty cheeks and thinning hair, I couldn’t help but feel after all of this a fond affection for the man. “Hi, I’m Jennifer Galloway.” I hadn’t time to answer before the wife stood from the couch and took my hand in both of hers. The tall, blonde, smiling, finally satisfying wife. “And I’m sorry. I didn’t catch your name.” “Clarence Richards,” I said.

Very kindly Nicholas asked if I wanted a cup of coffee, obliged me the final contents of a low sugar bowl, and invited me to stay a while. I took him up on both offers. He was very apologetic when he said that he had a dinner with some trustees in just a half hour. He rolled his eyes when he mentioned the trustees and Jennifer half-covered a giggle with her hand. Just the dull duties, he explained, that came with the job of a writer in residence. He asked where I was from and with no desire to be truthful I answered with an obtuse “down South.” That seemed to satisfy him and no follow-up questions came. He asked if I read a couple writers who had been especially influential upon him, and when I responded that I had not, he didn’t seem particularly disappointed. He said, now chewing on the end of a pen, that his favorite protagonist was still small-town America and his favorite antagonist was the foil of conformity to an outdated American dream. He noted, and here is the obvious, that occasionally what reviewers refer to as a “slice of life” was occasionally a slice of his own life. He sprinkled autobiography. He rubbed his cheeks in amusement and feigned embarrassment. “I think I have a few copies of my latest novel left,” he said. Then he pulled a book called A Long Winter at Wendell’s Farm from a stack beneath his desk and signed it: “Dear Clarence, Here’s something for a slow summer weekend. Yours, Nicholas Galloway.” I thanked him and he thanked me as well. So as not to be left out, Jennifer thanked no one in particular. She blushed, which I found charming, and I left. As I left, I felt the air turn to a mild irritation. They would be spending the night with the trustees when they should be spending it together.

Nicholas Galloway did not remember me. Not long after I had last seen that boy who played violin for me in no clothing at all, we both became men. And at some point when he became a man, no longer hiding behind any facade of either wit or depravity, he forgot me. His elusiveness in my life drew me closer in bludgeoning longing to him than I had ever been when we slept side by side. I deeply desired to know myself in whatever way he once knew me. Yet I became useful in a way that I would never have wanted, but have come to accept, as one must accept things when there is no one to blame. With the whole of me fading, the smallest bit lasted. And nameless to him he called me a plot, a theme, a conflict, and finally, thanks be to God, a conclusion.

Zinnia Smith

smaller

The restaurant has colored Christmas lights terraced across the windows. The booths line along the two walls, meeting in the corner. Brown plastic looks like leather. Each window is covered with shades, making long horizontal lines of streetlight and shadow. We sit down at the table and the waiter brings us three waters, but my mother asks for bottled. My parents say they’re going to have the buffet. I ask for an order of eggplant. “You want the buffet, too?” I ask for the eggplant. “You don’t want the buffet?” No, thank you, and I ask again for the eggplant. “No, you should go look at the buffet.” This time I point to the menu and ask again. “No, I think you will like the buffet. Go ahead and look.” My finger still points to the broad white menu, mouth – ing the word eggplant, and the waiter gestures to the buffet, half-facing me now. “You will like the buffet. Anything else to drink?” he asks my parents. Eventually, he turns to me and asks what I want. “A Heineken,” I say. “Good.”

You should smile more,

This is similar but not the same as the time an old man sat next to me on the bus. Leaving the restaurant in Cambridge, I took the 77 night bus down Mass. Ave. I liked to sit next to the window, leaving the aisle seat open, just so I could watch the sidewalk and the car blinkers. When it was my stop, he refused to stand up. He shook his head and pointed down as if he had a bad leg, the one he used to walk to the back of the bus and sit next to me. Some others might know this grimy experience of close – ness between strangers while wearing a dress: my bare legs straddling his knees as my body rubs against his. I saw it happen to a friend this New Year’s Eve. An old man just walked up behind her and humped her butt. You know, it’s not the same, but it’s also like the time my college professor said in front of the class that my white dress looked see-through. “That’s your intention, isn’t it?” he stated in front of the room.

You know, it’s not the same, but when I raise my hand in graduate school, I hear in response: “Good girl.” You know, it’s not the same, but at a party, a guy loudly cursed me for not having sex with him the weekend before. You know, it’s not the same, but the man sitting behind me on the train leaned forward between the seats and whispered, “Suck my dick.”

I don’t want to be any smaller. I’m tired of being smaller. I’m tired of trimming and smoothing. After I decided that I was done being smaller, my hips grew out. My white dress once fell loosely over my waist the spring I didn’t eat carbs or cheese, and I ran at least three miles, six days a week. All that running made me tired, so now the dress fits tighter than it used to, and regardless of whether or not it still fits, I don’t feel comfortable in it anymore. How could I? I didn’t even feel comfortable when I didn’t eat carbs or cheese, and I ran at least three miles, six days a week. Those were the days I lived on a college campus. I didn’t understand how important appearances were there, not until I left, and I realized one of the main things I learned is how to behave like an obedient feminist.

On the subject of cars,

I drive around the Hamptons in the month of June, leaving work in the evening and heading west, past the fork. In the evening, the sky is pink and violet where it meets the trees, blue and cool. The same radio ad plays every drive to and from work: “Honey, I’m ready to take my top off,” the sultry voice says. “Oh yeah?” he replies. The ad is for BMW convertibles.

On the subject of sandwiches,

I see my college friends and I marvel at how small they are. Flat hips and little arms. We’re still competing to be the prettiest girl at the party, and trust me, none of us will openly admit to this because we all like to pride ourselves on our independence and feminist thought.

(But my ass is looking good these days.)

For the record, the most liberating thing I did in 2016 was not the day I voted for a female president. It was eating a sandwich. A full sandwich made from two slices of bread, sharp cheddar cheese, sliced turkey, and extra Dijon mustard.

The White Dress:

I thought I would wear that white dress today. After shifting around my closet, moving plastic boxes of packed winter clothing, wondering perhaps if it was buried beneath the heavy wool, I remember. I got rid of that dress in a trash bag.

Light feminism, not unlike Diet Pepsi. I have female friends who didn’t vote in the presidential election. Maybe this is more a reflection of our privilege associated to race. Meaning: it’s safer to be a white woman than a woman of color in this country. Maybe this is more a reflection of our privilege associated to gender-identification. Meaning it’s safer to be a cisgender woman than a transgender woman. Maybe this is: they just don’t care about politics. Maybe this is: they didn’t have the time to make it to the polls? Maybe this is: they’re secure enough in their financial position, it really doesn’t matter, this way or that? Maybe this is: the ineffective cause-and-effect of the suffrage? Maybe this is ________?

Maybe we weren’t really meant to vote at all.

My hips grew wider and my voice got louder. In my disappointment, I’ve grown angry. Now I’m “that bitch.” A friend once described this readjustment in the world by experiencing a group of liberal-minded friends she was workshopping with: “Oh great,” they would say when she opened her mouth. “Here’s ________ with her ‘feminist talk’ again.” Is it too much to ask to quit it with the air quotes? Is it too much to ask to have people stop projecting emotions onto my body? Is it too much to ask to be treated like a human?

The British suffragists chose to wear three colors: purple for dignity, green for hope, and white for “purity in public and private life.” The Congressional Union for Woman suffrage in America, 1913, declared: “White, the emblem of purity, symbolizes the quality of our purpose.” When, July 9th, 1978, they marched for the Equal Rights Amendment that never passed, all the women wore white.

We strive for our feminism every day. My white dress is not the same as yours. But with my eyes, I see you. But with my ears, I hear you, sister. I will be quiet for you, to know you better. We ensure the rights of white women are the equal rights for women of color are the equal rights for transwomen are the equal rights of disabled women, free from persecution of religion, and this is when we become free. The very same day we wake up in the morning, and sit down to write and write about the beginning sun settling across the floor over the little lump of sand piled by the door, such a quiet thing.

My thoughts on being a woman writer:

“Politics is a dirty word”:

You know, it’s not the same, but it’s sort of like how Donald Trump said: “Grab them by the pussy.” Remember that everybody? Grab. Them. By. The. Pussy. That one time President Donald Trump said: “Grab them by the pussy.” Are. You. Fucking. Kidding. Me. America.

“You know,” my therapist says to me as he places his hands in his lap. “Words are funny things. Have you ever written to yourself?”

I ask him what he means.

“Writing to yourself,” he elaborates, “like a letter. You could find it very helpful in training how to talk to yourself. The tone of voice that you use. You’re a writer. Haven’t you thought about how words sound?”

Have I thought about how words sound?

“Like . . . words can vary quite a lot,” he raises his palms upwards now. “Words can either feel like…oh, I don’t know…. Let’s say, they can feel like you’re naked on a cloud with Brad Pitt. Or words can feel like you’re being molested by Donald Trump.”

In regard to academia,

I’m struggling, you see. I’m wary of my arrogance, but I’m wary of self-censorship. Am I a fumbling pedantic? Am I really so tortured? Or am I just a woman in America. Better to speak softly. Better to simply wonder. Better to write personally. “Like this section here about your breakup, this part here about your boyfriend, we would like to hear more about that.”

I keep getting in trouble, and I’m losing my friends.

“I don’t think it matters what we read,” they said from across the table. “It matters more what all of them read.” They wave their hand around in the air, encompassing all the people outside the small square classroom who might be affected by the sexism of a 1950s Italian novel.

“I think you think it’s a bigger deal than it actually is,” they say.

Has a man ever been critiqued for the simple act of writing idea-driven essays? For fashioning rapidly a jeremiad? Does it even matter? I don’t see how I’m not in these thoughts; I don’t see how my active thoughts cannot be—

maybe I’m just dumb,

better to be smaller.

The part about the breakup:

“This kind of outrage doesn’t harm anyone except the self . . . Breakups thrill on a pitch of outrage . . . It was the moment I stood on the sidewalk next to the ferry and the boy from New York shook my shoulders good-bye, mustered a brief “I love you.”—That was the moment to realize outrage might reside for an extension of time. And it did, and then it didn’t.”

I was drunk and lying across a fold-out table under a white party tent. He asked me if he could, and I said no, and he did it anyway. I pushed him away, but still slept with him after, because I thought I still loved him, and so I overlooked certain things . . . and so, how the whole thing really ended: me pulling out a tampon in the back of his car.

It makes me think about all the times I didn’t want to, but I did it anyway, because something told me I was responsible for it, something confusing love and commitment and care, and something confusing womanhood, and I didn’t have any friends to hold my hand while horizontal, or mothers whispering in my ear be safe. And the breakup never really ended, because I still have to remember how the I man I loved didn’t listen to me when I said “No,” how a man who loved me could still violate me, across that wavering line of intimacy and trust, because it was pleasurable to him.

It didn’t end at a ferry station, not really. So I remind myself that the story people tell is not often the true story, if a true story is defined as a complete story.

All I’m saying is that I want the authority to write nonfiction like Borges writes Fiction:

The other one, the one called Zinnia, is the one that things happen to. I walk through the world, and notice things that I’m not sure she sees. Although, at times, I sense a numbness about her eyes, a dozy glaucoma. She says lovely things as we pass the pink and white shivering cherry blossoms on the promenade. Where I feel like I’m taking up too much space along the cross-streets of the city, 46th between 7th and 8th, she physically cannot exist in too much space. She speaks about the future and the past with such ease, they manifest themselves into the expression of the present, and amongst friends, amongst the ingenuous chatter of dinner parties, she quotes writers and thinkers like incandescent music notes: “everything about her was warm and soft and scented; even the stains of her grief became her as raindrops do the beaten rose.” She crawls into bed with dry hair, and takes her showers in the morning, and sips her tea sitting by the sliding glass doors facing the garden, she, looking longingly at the patio furniture for the warmer morning air. Oh, she knows how to walk the length of a tightrope while balancing a toothpick on the tip of her chin and from 300 feet above as she glides like water across the line. On our walks through the city, the bend in the path hugs the sooty river, and we pass the time in stilted conversation that is deceptively imaginative, until I close the door of solitude behind me and face my empty living room with the armchair and tarnished standing lamp with no substantial thoughts to suffice that voracious space. But you see, can’t you? You must know that I notice the cherry blossoms, too. I notice how the sun rises. I notice the thin crooked neck of the Virgo, the stainless demure. I’m more aware on the street of which way the eyeballs switch, watching. Yes, I admit that as I wash the burned chicken fat from the bottom of the pot, my mind resurrects the past into present emotions so that loves lost are loves needed and dreams dreamt are goals broken, and this makes my mind at times move languidly like a Lazarus. At 75 Main in Southampton, over white napkins and dinner plates of black-pepper tuna, I quoted the writers like she does; I quoted the thinkers like she does. But my words were more like ice cubes falling into an empty glass. I do not not have the same reverence in the classroom as Zinnia does, not the same respect or appreciation, but I know the reason for this, because I can see when no one else can how she bites her tongue. In our shared mind, I hear what she is really thinking, and I hear all her arrogance, her intelligence, her anger. Sometimes on a return trip along the LIRR, I see her sitting in a seat next to the window, her forehead tilted against the black glass watching the world smear past in futurist assault, and she will look up and see me and wave. I sit next to her. Her mascara has smudged like the artist’s charcoal, and so I know she is tired, and so in relief, I know our conversation will be true, because what is being if not truth? (And this is why Zinnia is not.) During these short train trips, the whole world starts to swim together, but under me still simmers the sweetest desire to be more like her—to be more lovely and kind. I smell the scent of the Moroccanoil that lingers in the raptures of her wavy hair, as if it, a scent, knows that it is a delicate thing and wishes for the strength to stay to her person. But being so near, only I know the chill rising off her forearm.

And I do think if maybe people listened more closely then we, Zinnia and I, would be happier for it.

Appendix:

[An Article Online]

“Help! My Boyfriend Secretly Taped Me While He Was Away to See if I’d Leave the House. Is it OK for me to be mad?”

[Overheard at a Starbucks]

Conversation 1:

“What’s your favorite subject in school?”

“Physics.”

“Really?”

“Yea.”

“Really? Wow. Huh. Wow.” . . .

Conversation 2:

“What’s your favorite thing to do outside of school?”

“Snowboarding.”

“Really?”

“Yea.”

“You know how to do that?” . . .

[My boss addressing a freelancer’s late assignments, at work]

“She probably has pregnancy brain . . . I’m not saying that to be sexist. It’s a real thing.”

[Over the phone, 8:30am, at work]

“Are you okay? You sound upset.”

[4:45pm, unscheduled review meeting]

“We hired you because you were supposed to be smart.”

[In conversation with my Grandfather]

Grandpa: “So . . . Zinn, how’s school?”

Me: “Good, I’m thinking about my thesis advisor . . .”

Grandpa: Hm.

Me: “I’ll be teaching a university course in creative writing . . .”

Grandpa: Hm. Me: “I taught The Second Coming last week.”

Grandpa: .

Me: .

Grandpa: “

How’s your brother?”

Shilo Niziolek

Swarming

There are hundreds of birds in the towering cedarwood two houses over. I can hear their ceaseless chatter; they are so busy making plans. I can’t identify birds by their sounds, and most I can’t even identify by their looks. The only birds I know by look are the crows, pigeons, blue jays, ducks, geese, swans, robins, seagulls, and blue herons, which are my favorite of all the birds, so stately on their tall, thin legs. More of the twittering birds fly in every few minutes. It is a miracle the tree can hold all their weight. I wonder if I knew their names if they’d come to me when I’d call. I want to say, come sit in my tree silly birds. It is me you came for. But I do not call, and they do not come.

I had that hollow feeling earlier again. I took a shower and was exhausted by it, as if I had just run a 5k race. I wanted to cry, but that is nothing new. Or if it is new, it is only about four months old. Again, this is probably just another case of me lying to myself. I think I have been crying since I turned seventeen. Maybe when I turn twenty-eight it will stop. A good ten-year run. I came outside to be rid of the feeling, and even though the dog shit hasn’t been picked up in at least two months because Andy’s jaw was broken by someone he called a friend, and I have been so sick and tired that I run out of energy almost as soon as I stand, it is still nice to sit out here. All it takes is the ability to tune out my sense of smell. Then I can hear the birds; I can watch the dogs grapple with each other and do zoomies around the yard. The wind can lift the long grass jutting out in clumps from the recent rains that I wish would come back. It is easy to forget how much I need nature when I am stuck in my own misery loop repeating things I don’t need to rehear.

Suddenly the birds become silent. I look up and they all flush out of the tree at the same time. The dogs feel the overbearing silence too, and they are trying to fill it with barking. I want to cry more than ever now.

Someone in the distance is sweeping something. I don’t trust people who use brooms to sweep their driveways and the streets in front of their houses. One day I watched a man sweep all the yellow leaves off the street in front of his house, and then he proceeded to do the same thing in front of his neighbor’s houses on both sides. If I was the neighbor I’d be mad. Leave my leaves alone, I’d think. As soon as the man went back in there was a gust of wind and a couple leaves trickled into his clear pristine black tar, and I laughed out loud, as if I’m not always trying to stave off death and the death of my loved ones.

A couple days ago I went out to my mom’s house, so Andy could work on her car. We went into her craft room, so she could show me something. She told me the weird vibrations she has been having in her feet for the last year have now traveled to her calves. She said she feels it all the time. She said, “I haven’t told dad yet. But it is MS, I know it is. I can feel it in my body.” And I believe her. Nobody knows their own body better than a woman. It is the same way I knew, all summer long, that something wasn’t right in my stomach, that the center of my abdomen was in some sort of deep, wounded pain. And I was right. When it comes to our bodies, we are almost always right.

I got the diagnosis the other night while we were at a hockey game. The entire time, while young men were brawling on the rink below me, the continual deep ache under my ribcage persisted. Just as I was thinking how I couldn’t do this much longer, how I must have a diagnosis soon or I will split in half, I got the email. You have a small intestine bacterial overgrowth. The email read. And right there, surrounded by strangers my eyes welled with tears. Answers. I had wanted answers so badly. I knew. We always know. That is how I know my mom knows what is happening in her body.

She is in Ireland now, for her fiftieth birthday. Ever since I was a little girl I have known that my mom has wanted to go to Ireland. I am so happy that she finally made it there, and at the same time I am worried sick about her. Each time a picture is loaded by her or my dad I can see it there, the ashen skin, the bags under her eyes that haven’t left since she got really sick about four years ago and discovered that her thyroid had devoured itself, as if it were a lemon scone or jelly donut. I can’t really believe that she is fifty. Or that I am twenty-eight. I mean twenty-seven. Or that my eldest sister is thirty and my littlest brother twenty-five. The dogs keep aging too. Roxy, our almost nine-year-old dog, has three more lumps that have cropped up that we have to get removed and tested for cancer. She already had three removed last winter when she had knee replacement surgery. Two of them were cancerous.

The outside world is breaking right now, as it does over and over again throughout all of history, ever. I should be an active advocate of society. I am a woman. I am part Native American and part Jewish and a whole lot of other white races. I should be out there fighting the good fight. But I don’t have it in me. So many people would call that a privilege. I’ve seen the posts about it on Facebook, how if I am able to not be out there fighting it’s because I have the privilege to not need to. And it hurts, like a deep mortal wound. If things continue as they are, I will lose everything. I will lose my health insurance. I will lose the ability to get my one remaining tube tied so that I will not die from my next ectopic pregnancy. But I just don’t have the energy to fight. Is that privilege, to be so sick that a shower makes me tired? It sure doesn’t feel like it. I waiver in between dropping out of school constantly though I love school, and though it is the only thing that is helping me pay the bills now. But getting to class can be so hard. Sometimes it is hard enough to get off the couch.

I was reading up on my new condition. Apparently, I am suffering from malnutrition, because the bacteria overgrowth prevents all the minerals, nutrients, and vitamins I am putting in my body through food and supplements from actually getting into my bloodstream. The treatment for this whole thing takes four months, and if that doesn’t get it all, another four months. I wanted to ask if I would be sick during treatment. Sicker, I guess, is the correct terminology, but my tongue froze in my mouth.

The sun keeps shining, but I am waiting on the rain. I need to be cleansed more than ever, though inside I feel like the ice storm from last winter: lavender bush frozen in place, sheets of ice on everything, crackling under foot, icicles dripping from the benches and trees.

The birds have not come back. Will they ever? The next time I have sex it will probably be June. Andy is learning how to expect so little from me. But that’s the difference between us, I always want more than what the world has to give me. There is a crow outside calling out a lonesome call. Maybe one day I will sprout wings and fly above the land, only to wish that I was a salmon swimming upriver to the sea.

Amanda Salvia

(Nonna, 2016)

On the front door of my grandmother’s apartment is a small sign that says SHALOM in English and in Hebrew—the greeting used by Jewish people, a salutation that means peace and wholeness. The plaque is simple, white ceramic with hand-painted red and yellow flowers along the edges. Just below is a beautiful tapestry depicting a Russian church; the cupola is made of golden yellow silk, offset by scarlet velveteen. Stiff brown ropes are stitched into the tapestry to represent trees in this landscape. It’s a favorite among her neighbors in the senior apartment complex she’s lived in for almost thirty years. Her hallway is a row of divorcées (like herself) and widows, and a group of them have coffee every Wednesday morning in the lobby in front of my grandmother’s door.

My grandmother is neither Jewish nor Russian, but a four-foot-nine Italian woman we call Nonna, and right now, she wants neither the Shalom plaque nor the tapestry, neither peace nor beauty.

“They mean nothing to me,” she says, hardly glancing at them before she snaps around and walks away in disdain. “You take them.”

So I do.

As soon as her last child moved out, Nonna got a passport. Using money from some smart investments, she spent her fifties and sixties travelling—to Turkey, Croatia, Israel, Moscow, Punta Cana, Egypt. She never took photos because she thought nobody cared to see them, saying, “If I ever try to show people pictures of buildings I’ve seen, take me out and shoot me.”

Instead, she bought art.

Every wall of her home is covered with paintings, photographs, and tapestries; her tabletops are crowded with figurines, sculptures, and pottery. In her tight, cramped script, she has written on the back of every piece the country and year in which she bought it. Together, these pieces make up a timeline of the last twenty years.

Soon, she is moving to a smaller apartment, and I am helping her decide what to take. So far, we have packed a framed doily—a wedding gift crocheted by her mother—that had hung in her hallway and an ornamental wooden birdcage the size of a toddler that had sat in the corner of her living room, holding her extra yarn. Then we unpack the doily because she decided it was ugly, and then we repack it because she says it’s her favorite keepsake.

These moments seem normal now.

The electronic clock in her kitchen is one giveaway of her Alzheimer’s—it blinks the date, the time, and the day of the week. The way it takes up an entire corner of her counter means she cannot miss looking at it. A second tell is that she cannot remember why she has to move. How can we explain?

“Because last month, you got lost on the walk to your friend Terri’s apartment on the fourth floor.”

“Because you called Lucia four times on Halloween to ask what kind of food you should bring to Christmas.”

“Because we don’t know if you’re eating when you’re here by yourself.”

Finally, we sigh deeply and lie to her: “They’re raising the rent, Nonna. You can’t afford this apartment anymore.”

A third tell is that she doesn’t want any of her art.

“Amanda,” she says, picking up a large stained-glass vase that she got when she returned to her native Forlì del Sannio, Italy, in 1994. It was only the third time she’d been back to visit her cousins since she’d immigrated at age five; her mother had packed up her and her two-year old sister, and the three of them boarded a boat to Ellis Island where her father awaited them. The vase is nearly the size of a globe, and delicate, with pastel green, amber, and pink glass color blocks. She never put flowers in it, but sometimes lit a candle behind it so the light was thrown through the sheer panels, watercolor projections flickering on the top of the coffee table where it always sits. The vase has been the lodestone of the apartment ever since she convinced the customs officers to let her cradle it in her arms, rather than store it with her luggage, during the flight back to Pennsylvania, “Take this. I don’t know what it’s here for.”

I wrap it up carefully and place it in a box, knowing she’ll ask about it again in an hour. I put the plaque (Israel, 1992) and the tapestry (Moscow, 1999) in the box too, to be taken to her new apartment, so she might have some sense of normalcy. Perhaps she could even forget she’d moved at all.

Nonna avoided tourist spots purposefully—“I want to see how people live,” she used to say, “not how other people vacation.” She always opted to see the real experiences of real people. Growing up, she watched her father and mother struggle as poor immigrants in northern Pennsylvania—he worked in a paper factory and she raised their daughters— and watched them make a life for themselves that was simple and ordinary and, by the nature of their immigration, miraculous. She valued daily life.

This is how she met her friend Ana, a woman she connected with in Punta Cana in 1995. Ana was stringing necklaces with small shells while crouched at a milk crate. Her inventory was spread out in front of her when Nonna approached. Nonna spoke little Spanish, and Ana, little English, so they relied on gestures. This story is a family relic itself, and I have heard Nonna tell it so often over the years that, even now, I can see her recreating it. Their broken conversation went something like this:

Jewelry? Ana waved to her display.

My nonna must have nodded, looking carefully at Ana’s merchandise, fingering the shells. She had chosen one to buy when she saw the long string of cloth beads around Ana’s neck. The colors were bright—textured fabric of golden yellow, teal, and red fixed into balls and strung along a thin cord of burgundy. Motioning toward it, Nonna pointed, I like that one.

Ana smiled and accepted the compliment. She was about to take Nonna’s money for the shell necklace when Nonna pointed again, and then held out the money in her hand, asking if she could buy the colorful beads.

Ana, surprised, shook her head, waving her palm over the necklaces on the crate, No, these are for sale, moving once again to sell the shell necklace.

But Nonna was insistent. Pointing to Ana’s neck and smiling, she admired the necklace Ana wore. Nonna moved her hands to mimic sewing to ask, You made it, too? Ana understood, touched the necklace and nodded, no longer defensive, smiling.

Nonna sat down and pulled a gold bracelet off of her own wrist, pointing to a tiny word etched inside the cuff, Italia. She held it out to Ana, who hesitated before taking it. Nonna nodded her encouragement, so Ana examined the bracelet and slipped it on her wrist, holding her arm out to admire the way the sun made the gold shine.

Nonna pointed from the necklace to the bracelet, and to Ana. Exchange? After a moment, Ana pulled the necklace from her neck and handed it to Nonna, and the two women spent the afternoon sitting behind the milk crate, “talking” and selling Ana’s wares.

Nonna took down Ana’s address and, back home in Pennsylvania, mailed her a thank you card with a picture of her wearing the necklace; she received a full letter back, in Spanish, with a photo of Ana’s daughter wearing the bracelet. For ten years, the two women exchanged cards and pictures every Christmas.

Now, Ana’s necklace is sitting on top of a bag of old clothing and worn shoes, to be taken to Goodwill. Its colors have faded and the fabric is fraying in where it meets the suede, worn thin and sagging under twenty years of touch. I pick it out of the bag and put it in a box. I am over-packing, the plaque, the tapestry, the vase, even the necklace. Her new apartment is half the size of this one and very few of these pieces will fit, but she has spent decades collecting treasures and I cannot bear her to lose them. Even if she cannot remember why, she valued these things, these stories. I value hers.

“Amanda, what is this?” Her voice is high, and flustered, so I drop mine to balance us:

“It’s a mosaic, Nonna. You bought it in Greece.”

I hold on, white-knuckled, to balance, and to these trinkets, because this is my last hope.

These mosaics and paintings and sculptures and photographs and pottery make up her last twenty years, and I have a childlike fantasy that I cannot admit out loud: that these remnants of her life amassed in her new place will force her to remember the rest, like they are puzzle pieces and having them all together will yield a picture of the rich life she’s forgetting.

I cannot help it; I miss the grandmother that her belongings tell me she used to be.

“Oh Madonna, Amanda,” she says like a curse, reverting back to her native Italian. English couldn’t quite convey her frustration. “Why do I have to move?”

I leave the room so I don’t have to explain why I am crying.

Her den is more lived-in than the rest of the apartment— it’s where she’s always sat at night, knitting and watching QVC with her credit card until she fell asleep in the recliner. (One of these late nights a couple of years ago led her to send me a package of 40 granola bars, which I received in an unmarked box with no return address. When I nervously called around asking who had sent them, and why, she told me she’d done it because “the man on TV was very handsome.”) She doesn’t do much ordering anymore.

There’s very little art in the den—just a couple of small figurines of women holding baskets on their hips (Croa tia, 2001) and some painted coasters she bought in Egypt (1997). Mostly, there are photographs.

Every surface is covered with framed pictures of her children and grandchildren growing up. I recognize my parents’ wedding; my dad, smiling and with a full head of hair, is dancing with her, and she is caught mid-laugh because his tie clip is snagging her purple dress.

There is a snapshot of my two-year old nephew, my brother’s son, propped against the other frames. She has written “My Leo—Matthew’s child” on the back for when she can’t remember who he is; her dementia had already begun by the time he was born. I am sad for him, that he will not know Nonna when she could know him too. As I am slipping the picture into a frame, I remember her smiling as she watched him run across the yard before turning to my aunt and asking, “Lucia, whose baby is that?”

I box up all the pictures, taking particular care with the photo taken at my uncle’s wedding six years ago. In it, she is seated on a bench outside in the sun, and all five of her children are standing around her, smiling. Circumstance and Italian stubbornness, a reaction to her bad divorce, have made it difficult to gather all of them together; it’s the only photo of them that’d been taken in decades. She looks beautiful and serene, in control and happy.

In every country, Nonna bought a cross; they hang on her bedroom wall in rows, the very last thing she sees before she goes to sleep each night. She raised her children Catholic, keeping with her Italian heritage, but stopped attending church after her marriage broke up. On her bedside table is a well-worn Bible with several pages dog-eared.

I’m thinking I shouldn’t be looking at the crosses; they’re on display, but only in her bedroom, and their religious significance feels like an immensely private part of her. I wonder what she thinks when she sees them, why she chose the ones she chose, and how personal the decisions must have been. My chest aches when it occurs that she probably doesn’t know now.

“Take them,” she startles me. I turn around, and she is staring at the wall of crosses. Her hands are clasped in front of her waist, and suddenly, I see her wrinkles, her thin grey hair, and her stooped shoulders in a way that never made her look old before. She is beautiful and calm, but lost and unhappy—in a moment of near-clarity, she seems to accept that she cannot remember. “I don’t even know where I bought them.”

I do as she asks, and as I lift each one off the wall, I am overcome by the colossal weight of all of the things I’d packed. These are measures of a life fully lived, of my grandmother—the immigrant woman who raised five children, who helped send her younger sister to college, who came to her granddaughters’ every dance recital. Who still made time to travel the world.

My hands are cupped around these memories, yet the failure of her recollection means they cannot be touched. Her story, erased. I pack to preserve what I can, but it will never be enough.

I pick a cross for my brother, a green stone with rough squares chiseled in. Nonna has written “Dominica, 1998” on the back in her spiky cursive. My sister, an atheist, gets a metal one with smiling people painted on it, which I hope she takes to be a celebration of humanity more than God (Mexico, 2003).

For myself, I take a small one that is just the size of my hand. The cross itself is brass, but around it are small pieces of colored glass, their sharp edges rounded out; deep ocean blue and bright orange and rich magenta, golden yellow and emerald green all strung along a fading copper wire that is twisted around and around the brass.

There is no place, no date, on the back of this cross, and I’m glad. The ambiguity is comforting; the knowing that I will never know which country it was made in. She doesn’t know either, and for a second I feel close to her in a way I haven’t for a long time.

“That’s a good one,” she says, touching my fingers that are closed around the beaded cross, “I always liked that one.” For a moment, we are still.

I wonder what goes through her head, if she is remembering buying the cross, or trying to. She chose these things because they once felt right to her, they suited her taste, they filled a hole she chose to seal with beauty. Whether she knows it or not—and more often, lately, she doesn’t—these things make up my nonna.

After a moment that seems suspended out of time, with her hand on mine, she breaks the silence. “Amanda,” she asks, “Why do I have all this stuff?”

I slip my cross into my bag with the others and begin pulling the rest down off the wall, wanting to say, “Because you experienced the world, Nonna.” Instead, I pretend not to hear.

TEXT & IMAGE

Em DeMarco

One Day in the Late ‘70s

CONTRIBUTORS

Questions and Answers

In addition to providing a biography, our contributors answered the following;

1. What literary character would you like to bring to life?

2. Where would you haunt if you were a ghost?

3. If you joined the circus, what would be your act?

4. What animal other than sharks should have their own week?

5. Eliminate one thing from your daily schedule without penalty or disapprobation. What would it be?

6. If you had a warning label, what would be yours?

7. You’re a new edition to a crayon box; what’s your color and crayon name?

8. Best thing to buy for a dollar?

We hope that you enjoyed their answers as much as we did!

Dr. Jodi Adamson, when not reading, writing, sewing, designing costumes, playing with her puppy, and watching too much Forensics Files, is a retail pharmacist who dispenses happy pills and shoots customers with assorted vaccines.

- Eloise but only if we were twins and both living in the Plaza.

- Pet store-plenty of animals to play with for eternity.

- Fortune teller.

- Dolphins. Very interesting mammals.

- Easy. My day job.

- Proceed with caution—wandering mind!

- My color is the color of the ocean as the sun sparkles down on it, and my name would be sea dawn aquamarine.

- One time I bought a mini banana split. Delicious!

Bim Angst’s writing in multiple genres has been recognized with a number of awards, including a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. “Fever” is from a linked collection of stories set in the 20th Century’s immigrant-populated mining communities of Pennsylvania’s anthracite coal regions. Angst lives in Saint Clair, PA.

- My guess is that a gigantic white whale cruises the deep somewhere, and I would love to see the great scarred beast.

- There are a few beautiful mountain streams in Pennsylvania I’d be content to hang around forever. Visit and we’ll talk.

- I’d be the lady with the voluminous skirts and scarlet lipstick who caresses and reads palms in a tent off the midway.

- Dogs. And hyenas, who aren’t dogs, but close enough.

- My good girl wants to answer, but my controlling crone does as she likes and doesn’t care what others think, unless she’s unkind.

- May bite like a spider. Or maybe, Will turn away if bored.

- I would love to be a grass green or deep turquoise but would probably be an azo orange named egg yolk.

- A two-pack of ballpoint pens. Pleasing, portable, practical: Fidget, doodle, chomp, draw, tap, write, scratch, point, probe . . .

Judith Arcana writes poems, stories, essays, and books, and she hosts a poetry show on KBOO in Oregon. Her newest book, from Flowstone Press, is Announcements from the Planetarium—poems examining memory, considering the nature of wisdom, and reflecting on the experience of aging into new consciousness. Visit juditharcana.com.

- Maude, from the novel & movie Harold and Maude by Colin Higgins.

- The graveyard where my mother and all of my grandparents are buried (hoping to meet their ghosts).

- Reading poems & stories to clowns who respond dramatically for the audience; I’d wear a gown of gold sequins & silver glitter.

- Bears.

- I would eliminate the evening backup (to an external drive) of all work done on the computer during the day.

- Unlikely to Seek Your Approval.

- The crayon, very dark blue, is called Deep Blue Sea.

- One frosting shot at Cupcake Jones in Portland, Oregon.

Bert Barry is the Program Director at Saint Louis University. He earned a B.A. degree in German and a M.A. degree in English from Washington University. He also earned a Ph.D. in English from Saint Louis University. He is devoted to the lyric poem, in all its countless variations.

- No doubt about it, Gandalf the wizard.

- Pennsylvania Station in New York—I am a train lover.

- Anything but a trapeze artist.

- Gorillas—our closest relatives.

- Meetings!

- “Do not ask a question unless you want an answer.”

- Sea blue/Beryl.

- Hot tea—at least in a few places.

Robert Beveridge makes noise (xterminal.bandcamp.com) and writes poetry just outside Cleveland, OH. Recent/upcoming appearances in The Literary Yard, Big Windows, and Locust, among others.

- The scientist who created the shapeshifting technology in Wendy Walker’s The Secret Service.

- Area 51. Mess with their heads a little.

- I’d be the IT guy. I’m always the IT guy. I can’t even be in the audience, much less in the ring.