TABLE OF CONTENTS

Issue 14

BOGGS / CURRY POETRY CONTEST WINNERS

Winner:

Peter Patapis for “I Ash My Body“

Runner-Up:

Tim Barzditis for “I wouldn’t live there if you paid me“

FICTION

The Path to Freedom

Courtney L. Novak

Sarah’s Baby

Anne Hosansky

Grief

Glen Weissenberger

The Doll

Vivian Lawry

Dinner and a Movie

Kerry Jones

Karma

Joan Presley

Broom Jumping

Mark Ali

Kamikaze, 1945

Burton Shulman

Aye Calypso, the Places You’ve Been To

Shelby M. Koches

POETRY

Witches Reminisce

Susan Johnson

Reverse Poem

Samantha Madway

Decree

Cindy King

rams

Laine Chmielewski

692 MPH

Garth Pavell

Empty Orison

Linda L. Dennis

Brothers Chosen

King Grossman

Please Come Off-Book

Kevin Kantor

Pinnacle Peak and the Star That Live There

Lisa Compo

Phone Call

AE Hines

Orbit // Obit

John Sibley Williams

Elegy for the Unknown

Dawn Morrow

Photograph

Serena Eve Richardson

Ass Backwards Live Free or Die

Gerard Sarnat

Meadows Unit

Lisa Compo

A Twist of History

Lynn Hoggard

The Craftsman

Ed Krizek

See Me

Donna James

Now that we’re dead, tell me where we lived

Vy Anh Tran

Houseboat in the Desert

Mary Ann Dimand

Out of Mind

Ruth A. Gooley

All Mine?

Eleanore Lee

Curious Debris

Susan Johnson

Counterturn in the Bear Pit

Lynn Hoggard

No Longer for our Amusement

John Grey

Objet d’Art

Alan Elyshevitz

Chekhov’s Gun

John Sibley Williams

At Dolphinaris

Meisha Rosenberg

Ritual for a Hummingbird

Linda Neal

Snake In the Woodpile

John Grey

Call It Dancing

Christine Terp Madsen

If someone asks, this is where I’ll be

Tim Barzditis

Blues

Brian James Lewis

The Wound in the Self Through Which We Exit

Victoria Anderson

Lionheart

Dawn Morrow

First Apartment

Suzanne O’Connell

Across the Park

Mark Belair

From Somewhere at the Bottom

Betsy Martin

Captivity

Dick Bentley

Contemplating the Toothache

Brad G. Garber

North Country

Charles Elin

Proposal: Purchase This Citizen a Bourbon

Gerard Sarnat

Compass

Mark Belair

Garden

Albert Wells Pettibone III

I GO TO SEE A PLAY ABOUT COMPETITIVE AIR GUITAR (REAL PLAY, REAL THING) AND WIND UP FEELING SEA SICK

Kevin Kantor

New Hampshire Lakeside (Lake Winnipessaukee)

Ed Krizek

The Bullet

John Grey

Beautiful Retribution

Brad G. Garber

Rewrites

Kevin Kantor

Carrying Coffins

Denzel Xavier Scott

Heart with Prickly Wings

Linda Neal

If They Come For Me

Dana Robbins

CREATIVE NONFICTION

Destined to Teach

Ronna L. Edelstein

Familial Paper Trail

Danielle McDermott

Dancing Reflections

Connie Flachs

A Roar Deferred

Carolyn Sherman

When in Rome

Paul Sohar

No Child’s Play

Ariella Neulander

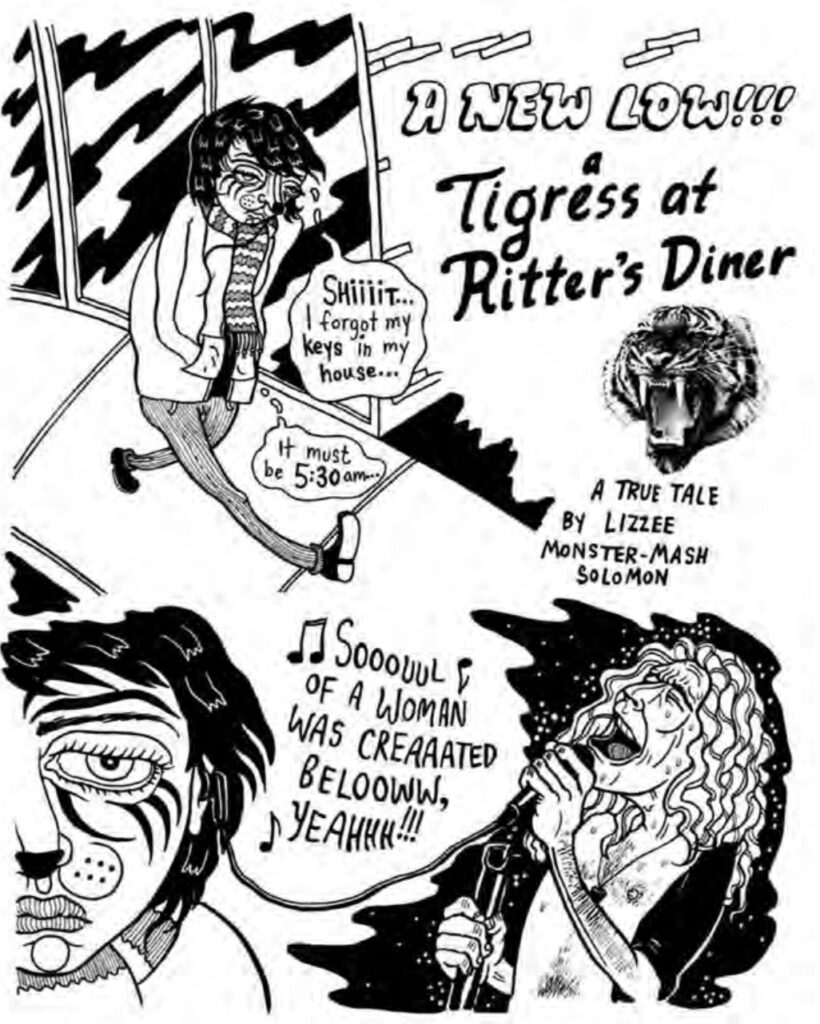

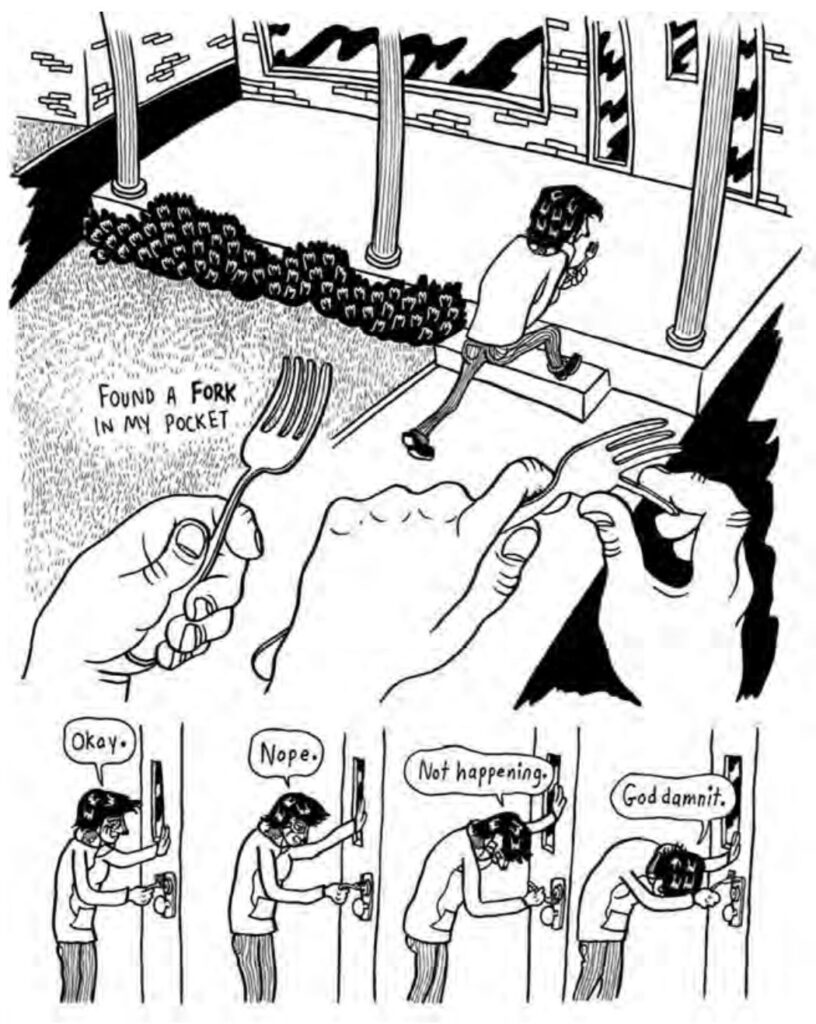

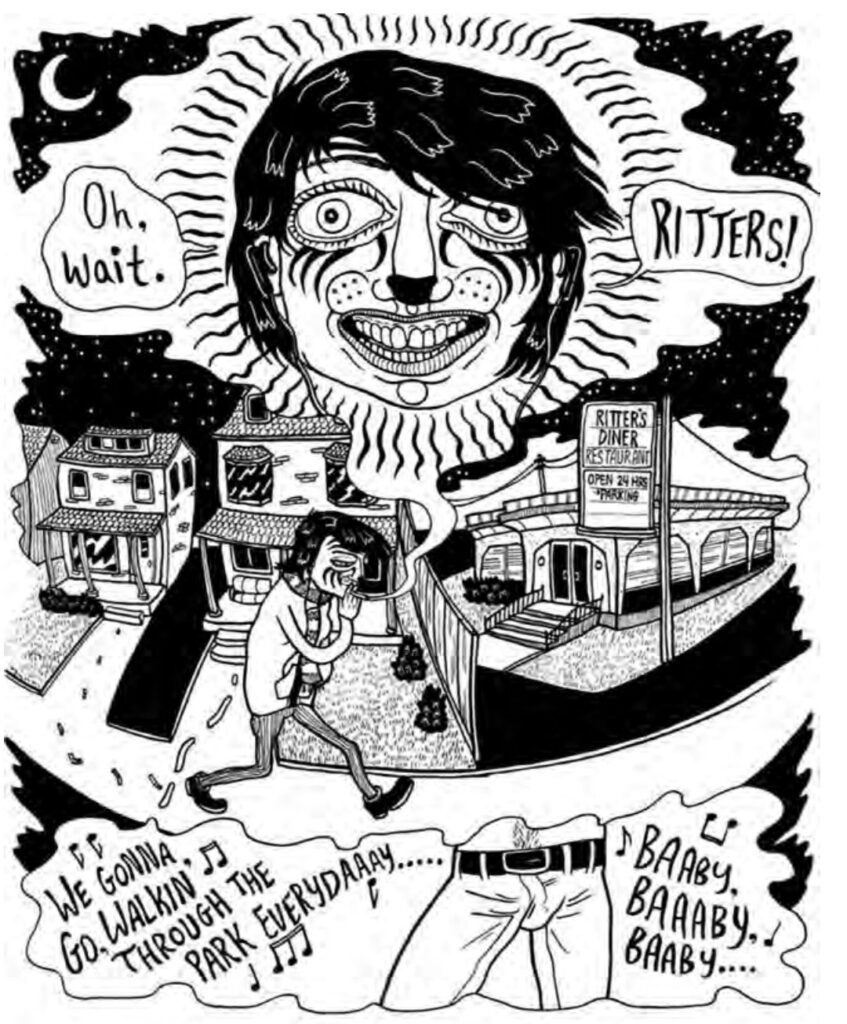

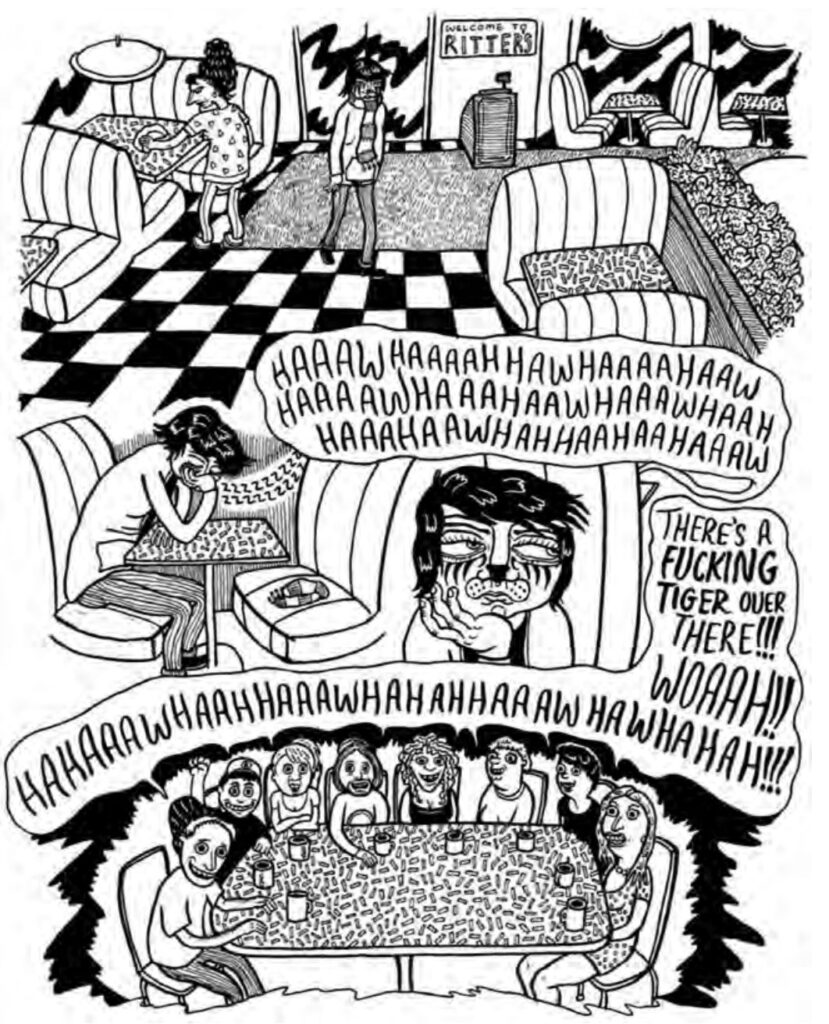

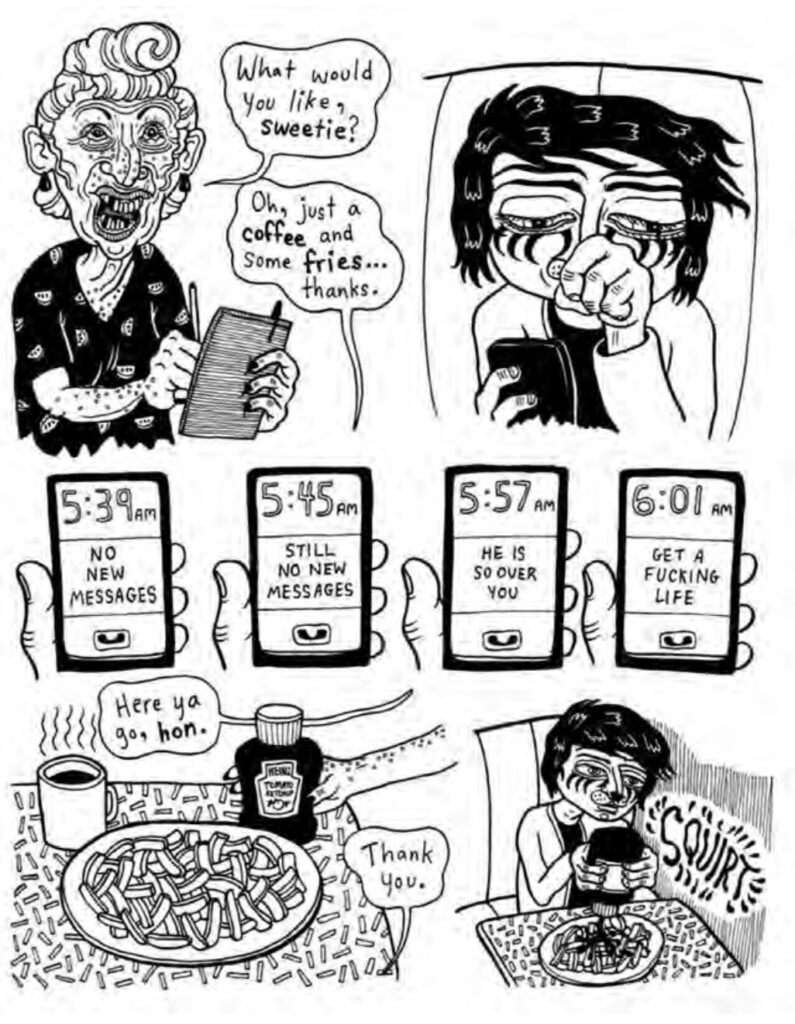

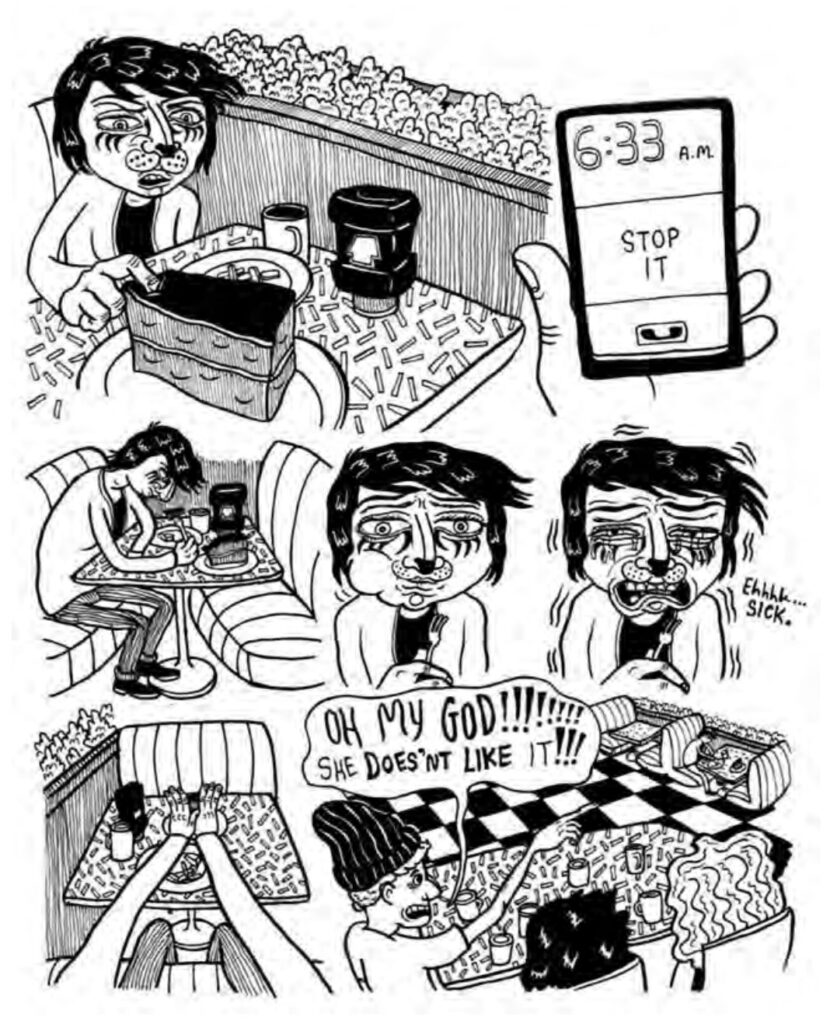

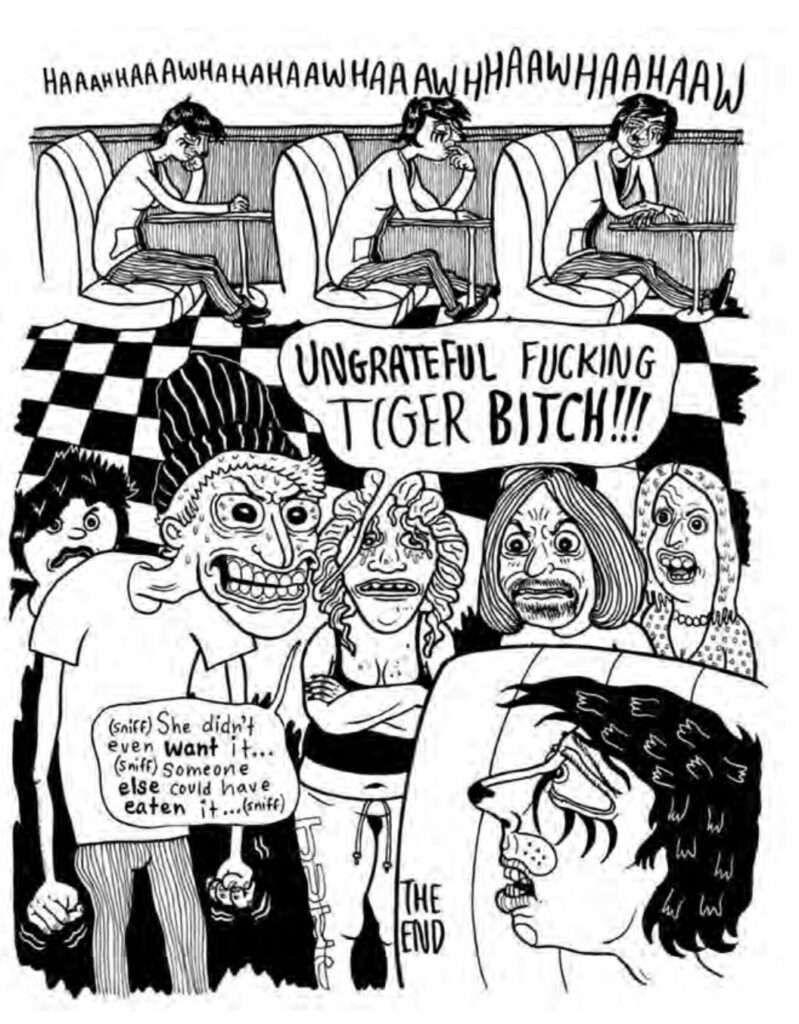

TEXT & IMAGE

A Tigress at Ritter’s Diner

Lizzee Solomon

BOGGS / CURRY POETRY CONTEST WINNERS

Winner

Peter Patapis

I Ash My Body

I nap in oral sex, wine and more weed without

realizing the darkness. I ash my body and wait

for the sear and the mass of grey flakes floating

off to the earth. I ash my body and ease my

temples, pour honey into my eyes. Overindulging

on late-night snacks and second dinners, I rot

in half-bottle increments. I recalibrate the 4 a.m.

insomnia into daytime hibernation. Tequila

sunrise burns into my cheeks, looks for the big

blue eyes and the next resentment. In this room

everyone wants one more song cigarette

connection, change in an atom, but in the end

I stare at the floor of the kitchen and chew alone

Runner-Up

Tim Barzditis

I wouldn’t live there if you paid me

[side A]

Last May, my brother escaped

with a girl to OK City.

Years before, the soft vibrato

of crawling storm clouds

twisted him silent.

Now, we write to each other

about whatever record

we might be spinning.

In my last, I offered a drunken

theory that “The Big Country”

was really David Byrne

calling us out for craving

that elusive sense of home.

[side B]

The circles I have carved

out for myself are small

and silver, echoes

of grey sky in black vinyl.

I am proud of you, brother,

how you’ve found enough

space to widen the shape

of your sound. I am still

here, engaged in a game

of vacuity, waiting

to hear the needle’s skip

and stutter give way

to new noise.

POETRY

Susan Johnson

Witches Reminisce

In those days you were either a chicken,

had a chicken, or could balance one

on your head. Superstitions inspired

suspicions which inspired accusations

of cats flying, bats conspiring in the pastor’s

well. Was that your dog talking, your pig

that spilled the cream? People were

deciduous as trees, rooted in steep hillsides

of belief that leafed out new commandments

each spring. Religion a fence bent, patched

with pitch. If you see something, swat

something. Life a boot to be broken in.

And once broken, how it cracked along

the seam like a ship’s beam. Your only

light a stick aflame, a window cut in ice,

a puddle reflecting the music of the moon.

When the young spoke, their tongues were

turnips. Always on edge, at the edge of

something you could not see, you could run

all you wanted but never escape. Inside

each forest, another forest. Thoughts rusted

like tools left overnight in a field. To survive

you pulled yourself up into your own nest

and watched as your neighbors’ was set on fire.

Peter Patapis

I Ash My Body

I nap in oral sex, wine and more weed without

realizing the darkness. I ash my body and wait

for the sear and the mass of grey flakes floating

off to the earth. I ash my body and ease my

temples, pour honey into my eyes. Overindulging

on late-night snacks and second dinners, I rot

in half-bottle increments. I recalibrate the 4 a.m.

insomnia into daytime hibernation. Tequila

sunrise burns into my cheeks, looks for the big

blue eyes and the next resentment. In this room

everyone wants one more song cigarette

connection, change in an atom, but in the end

I stare at the floor of the kitchen and chew alone

Tim Barzditis

I wouldn’t live there if you paid me

[side A]

Last May, my brother escaped

with a girl to OK City.

Years before, the soft vibrato

of crawling storm clouds

twisted him silent.

Now, we write to each other

about whatever record

we might be spinning.

In my last, I offered a drunken

theory that “The Big Country”

was really David Byrne

calling us out for craving

that elusive sense of home.

[side B]

The circles I have carved

out for myself are small

and silver, echoes

of grey sky in black vinyl.

I am proud of you, brother,

how you’ve found enough

space to widen the shape

of your sound. I am still

here, engaged in a game

of vacuity, waiting

to hear the needle’s skip

and stutter give way

to new noise.

Samantha Madway

Reverse Poem

When life gives you lemons,

squeeze the juice in your eyes

and call it fresh tears.

When the fisherman tries

to teach you to fish,

have him show you

how to put hooks under

your fingernails, then glide

around the swimming pool,

catching nothing but strands

of yourself that come loose.

When you take a penny,

empty the whole tray,

leave only smeared fingerprints,

and smirk with thinking those

will be worth something someday.

When you race, don’t

dare be slow or steady—

just remain certain

that anyone who bests you

isn’t best or even better, is

just a cheater with a blue ribbon.

When you’re a wolf,

cry out for help, then gnaw

to bone all who try to save you.

When you’re a sheep, baa

at all the spilled blood, then be a hero

for acting like a cotton swab

and soaking it back up.

Dawn Morrow

Elegy for the Unknown

I met my family in Wisconsin

once, a long time ago—

a graduation or wedding, some kind

of life-changing event.

But “family” seems like too strong a word.

A group of related things, says Webster,

all the descendants of a common ancestor,

and by that definition we’re all family

if you just go back far enough, or by dint

of a shared block, or school, or job.

What makes us family doesn’t make us kin.

Last week my Aunt Midge—identical twin

of my grandmother—died, and I pulled up

her obituary, surprised to see

“Genevieve.” All that shared blood—

I didn’t even know her name.

Serena Eve Richardson

Photograph

I became a photograph today at

1 p.m. while sitting on the back steps

smoking my last cigarette. The ghost of

girlhood flits from my face like melt on flame.

I became a photograph today due

to an accident my husband made while

snapping around with a brand-new lens in

the honeysuckle shade of the garden.

I became a photograph today and

now I am something from back in the day

sepia and old-school cool, ancestor

creased in the dust of an attic album.

Captured as this still image, I rose to

ripen into frame for a new being.

Donna James

See Me

with your hands, as if you are blind

and passage to my inner landscape

loops over contours of my body,

as if the code to me

hides at a distance in one fold or another,

in whole-palmed stroke of slopes,

textural subtleties,

mold of round,

the circular rise of my invitation,

slither through hollows; touch

as if reading me

gives to you sight.

Ruth A. Gooley

Out of Mind

The wind catches on the eucalyptus

and scratches its branches

like a squeaky hinge.

The dryness of the Santa Ana wind

steals the moisture from my arms and my lips,

fires them like paper.

The one-winged owl clings,

tethered, to the top of its cage,

eyes me with one yellow, unfriendly eye.

Ron spins to the cabin

like a boy with a new top,

leaves me at home, forgets to call.

No way to recall the breeze,

fill the air with fog,

give the owl back its sight,

the eucalyptus her leaves,

her scent. I sit on the rocker

and hang, out of place, out of mind.

Eleanore Lee

All Mine?

Agreed: this world’s our home, we’ve got our room and place.

It’s called “squatters’ dominion” under Common Law:

Just stay, and make your mark, and stamp it firmly: “Mine.”

You can see our lights from far-off outer space.

For thousands of years this world’s been ours. See all our stuff!

True. But we’re beginners. Here in this crowded world we’re new.

Long, long before our time, in steaming swamps.

Dripping toothy reptiles splashed and roared.

Through marsh and beach and pond for many million years

Lumbering lizards were Earth’s favored guests.

Earth was theirs they thought—them with their muscled wings,

their flapping lizard limbs,

Their smoking piles of eggs in prickly bristly, nests.

All gone now. Now us, we’re here. But only interim, I fear.

How much longer do we have? And after us…what’s next?

Alan Elyshevitz

Objet d’Art

He hopes for an unfinished epitaph and directs that, before he is

buried, his name be removed from his clothing.

-Keith Waldrop, “First Draw the Sea”

He’s acquired some object that belongs to the world, with

brushstrokes and a signature everyone knows. Nothing proves

its provenance, but it smells like the last standing gallery of a

bombed museum. The object depicts a saint’s suicide the Church

calls “martyrdom.” In fact it belongs in a farmhouse, forgotten,

awaiting exposure to the Prado or the Louvre. It’s displayed

on his balcony where three lazy cats—Dostoyevsky, Kafka,

Camus—share a stained cushion, shifting positions, each one

awakening from time to time with a melodramatic leap in its eyes.

He subscribes to a French newspaper he pretends to have the

vocabulary to read with coffee overlooking the plaza framed by

the Socialist Club and a five-hundred-year-old clock in a city that

thinks it’s in Belgium at the nexus of kunst and thievery. The crowds

go by like illegible writing, handkerchiefs pressed to their brows as

though someone important has died on a very hot day. Intolerable

are the church bells and footprints in yesterday’s puddles.

Fried foods and other corrosives widen the cracks in tourists.

For years he has been unremarkably alive, weathering time like

a ceasefire city, but his heart, beyond restoration, is not what

it was, betrayed by teenage cigarettes and the death camps

of grandparents. At sunset on the plaza the final survivors

vend what remains of protein they carry in their packages of

cosmopolitan skin. Food on a stick and quick sketches of

landmarks litter the cobblestones. The clock and the club

withdraw into shadows of dry history while the objet d’art

dapples then blurs, rehearsing decay for his killer ending.

Linda Neal

Ritual for a Hummingbird

On the dining room floor, a hummingbird

iridescent feathers on pale oak

like a piece of ribbon off a gift box.

Beak intact. No blood.

Knocked dead against the plate glass

with a security sticker

pasted to the bottom corner.

What does a hummingbird know

about security? What does it know

about invisible walls of glass?

How does anyone survive

pushed into invisible walls

of sunsets and feathers?

Cradled, soft in my hand

feathers tight to its body

the bird lay,

its two-inch beak

pointing to the sky.

Dark and round

still moist, its eyes

made me want to believe

it lived.

I laid it on the glass garden table,

wrapped in a paper towel shroud.

Should I make a coffin of sticks?

A sarcophagus of rocks?

A soft bed of leaves?

I left the bird, laid out there

for most of the day.

By late afternoon the miracle

of iridescence hadn’t faded.

Not a feather had moved.

In a remote village in Indonesia

the family polishes the dead ones.

Dresses them in feathers and lace.

Props Mom or Dad against a wall

talks to the corpse

until it’s time

for the funeral. Days. Weeks.

Years go by.

So, I talked to the bird.

You are beautiful, I said

and left it there,

went inside

to talk to the maple box of ashes

in my bedroom—

my father, my husband,

picturing their bodies

laid out iridescent in feathers

assuming they could hear me ask

what to do about the bird.

Brian James Lewis

Blues

The place is packed and people are dancing

to the rhythm guitar and drums

while the bass player, a cool cat in a hat,

holds down that bottom end

Smoke rafters to the ceiling and the lights

are low, making this tiny New York club

feel like Mississippi in July

The overworked AC groaning along

As the singer belts out a song about

“You can have my husband, but please

don’t mess with my man.” In a sexy,

slinky leopard skin dress that clings

To every curve of her lithe body

and gives you that smile and wink

that feels so good, like you both know

something that nobody else here does

Awww, yeahhh! And she’s shakin’ it

like you ain’t never seen nobody do before

while the lead guitar weaves in and out

sliding tasty little licks of sweet and heat

Throughout the song, dotting the I’s

and crossing the T’s with quick jabs

that grab your heart and soul tight

until it’s time to soar the solo into the

Night sky like a laser beam, making

the women scream and the men holler

draining out that bad news, bills due,

and the dead pick-up truck in the drive

Drinking cold beer from plastic cups

Eating barbecue and maybe slipping out

to your car to smoke a quick joint and

make some love with your baby

Under the light of the moon, bodies

rockin’, to the music still going on

while one lone cricket sings in the

gravel underneath your old car

Suzanne O’Connell

First Apartment

I was 20. It happened.

Tomatoes and squash grew in the garden.

Baked potato and Spam, cooking.

Television tuned to the news.

Traffic going by on 14th Street.

My first apartment happened.

My own little oven, my fireplace.

Cleaning all day happened.

My first bath in my own tub happened.

A stranger’s eyes sparkled, watched me

through the crack of my bathroom door.

I screamed. That happened too.

Later, the police asked why I screamed.

Why hadn’t I acted normal?

Dried myself off with a towel,

strolled to the bedroom naked?

Why hadn’t I acted normal?

Called them on my rotary phone?

Dressed slowly, a reverse striptease?

They would have come, they said,

they would have arrested him.

All that didn’t occur to me.

I was an unbaked cinnamon bun on a hot pan.

I was a newborn puppy.

I was a lily bending in the heat.

I was a scream I didn’t know I had.

I was only 20.

It happened.

It wasn’t normal.

Charles Elin

North Country

So many colors in a dying sun.

Insects, the last to find water,

shelter deep in the bark.

Mutations are under way.

Biology braces for its promise

of a melting pot.

Mark Belair

Compass

My dad driving, we were revisiting

his boyhood haunts

during an excursion

to his hometown in Maine

when the discussion came up

of directions and magnetic north

and my dad

drew a scuffed compass

from the glove compartment

and set it on the dash, a compass

that called north

wherever he directed the car—

angling it around a parking lot

with stops and starts—

until he gave up on the instrument—

which he nevertheless

returned to the glove compartment—

and resumed our tour

of once-thriving stores boarded up,

of old family houses fallen into ruin,

my dad, at eighty-nine, still

knowing his way around, the town—

with the mill buildings our family worked in

empty since their closing after the Second World War—

an Alzheimered version

of its glory days, a town

that my dad

would never forsake

no matter how forsaken

for as a fatherless boy

he could count on

the magnetic north

of its clear, stoic, French Canadian codes;

scuffed codes he still counts on—

as he grows more frail—

to guide his remaining

way.

John Grey

The Bullet

It’s in a rush because it has a flight to catch—

your leg.

It’s not a long journey

but, one microsecond late,

and you walk right by—

it crashes into a wall.

Its destination is the sidewalk

and it can’t get there,

if you don’t buckle at the knee,

drop like an elevator,

crash onto the pavement.

Luckily for the bullet,

it makes it just in time.

But there’s no more luck

beyond that.

Denzel Xavier Scott

Carrying Coffins

In America, it’s sad, but practical

to plan for a black child’s funeral—

preacher,

choir,

venue,

coffin,

R.I.P. shirts,

peace lilies,

photo collages,

limousine seating,

repass menu—

long before

our children dream

of walking across

a graduation stage

of any strata

or down the aisle

of their unlikely wedding.

We give birth to

casket-pretty babies,

who are the closet things

in this world

to the walking dead.

FICTION

Anne Hosansky

Sarah’s Baby

“Last stop,” the driver calls out again, staring at her. She’s the only rider left on the bus. She goes out the back door so she won’t have to walk past that puzzled look. All the drivers know her by now. The playground is almost deserted today, too cold for children to be outside, except for two little girls struggling with a rope. Why aren’t they in school? She won’t ask them. Children don’t like to be reminded of school. The taller girl is tying one end of the rope to a bench. “You can jump first,” she tells her friend. “I’ll turn.” But she has trouble holding the rope with her mittens on. “Would you like me to turn for you?” Sarah asks. “We’re not allowed to talk to strangers.” “I’m not a stranger. I’m here every day.” Giggling, the girls yank the rope free and race away. “You’re the strangers,” she shouts after them. She walks to the other side of the playground, past the swings and seesaws motionless in the icy air. Some swings have those little seats with bars to keep the children from falling out. That’s what she’ll put Jamie in so he won’t get hurt. She will push him high in the air. Hi diddle diddle you’re flying over the moon, she’ll sing. A woman is sitting on a bench, a baby carriage in front of her. Nearby, a little boy is trying to fill his dump truck from the sandbox. “Mommy,” he calls out, “it won’t dig.” “Sand’s frozen,” the woman says without looking up from her magazine. “No!” he shouts, kicking the truck.

“Play with your ball,” she says, tossing it to him. “And stop whining. You’ll wake the baby.” “I offered to turn the rope for them,” Sarah says, sitting on the bench. “But children are taught to be suspicious these days.” The woman glances at her. “Yeah?” “Even in playgrounds,” Sarah says. The woman shrugs, looking at the glossy face on the magazine cover. “I bet she doesn’t have to change diapers.” “What a beautiful baby,” Sarah says, peering into the carriage. “Boy or girl?” she asks, looking at the yellow snowsuit. “One can’t be sure without a pink or blue cue.” She laughs at her joke. “Boy,” the woman says. “You’re so fortunate.” “He’s my third. I’ve got another boy in kindergarten. I was hoping for a girl this time, but some people have no luck.” “No.” “You got kids?” “A baby. He was born six weeks and two days ago.” “That’s really a new one.” “He was baptized James, for my father. But I call him Jamie.” The woman’s watching the boy race after the ball. “Don’t run!” she shouts. But he trips and falls. “For Heaven’s sake,” the woman mutters, going to the screaming boy. His pants are torn. There’s a bloody cut on his knee. “Can I help?” Sarah asks. “You can use my scarf.” “No thanks,” the woman says over the boy’s sobs. “I’ll take him into the bathroom and wash his knee. I hope he doesn’t need stitches.” “I’ll watch the baby for you.” The woman hesitates. “We mothers have to help each other,” Sarah says. “Well, I suppose. . . I’ll just be a few minutes. Rock the carriage if he cries.” She pulls the sobbing boy toward a stone building, through a door marked GIRLS. Sarah reaches into the carriage and touches the baby’s cheek. “Soft as a marshmallow,” she murmurs. He’s whimpering. Picking up his pacifier she tries to put it into his mouth, but it falls out and he cries louder, waving his fists. “She didn’t even put mittens on you,” Sarah says. “Poor baby, are you cold?” She lifts him out of the carriage and wraps her woolen scarf around him. His head is banging against her breasts. “You want dinner, don’t you?” She starts walking, holding him tighter. “No more milk, all gone.” He’s hitting against her frantically. “Look at the swings,” she says, carrying him past them. “When you’re older you can ride way up in the air.” She’s near the gate. Across the street, a vendor is selling coffee. “Let’s go see that nice man.” The coffee smells good. She can’t remember if she had any this morning. Did she make it for Tom before he left for work? He’d been angry at her for taking so much time to arrange the toys in the crib. The teddy bear kept falling over and the music box wouldn’t wind. “Nice baby,” the vendor tells her. “How old?” “Six weeks,” she says. “And two days.” She walks on, humming the tune from Jamie’s music box. Love makes the world go ’round. . . She and John picked out that music box when she was pregnant because it was one of their favorite songs. “I want him to have a good start in music appreciation,” Tom had joked. So sure it would be a son. The music sounds fainter lately, maybe she winds it too much. “Love,” she sings to the baby. A bus stops at the corner. “Getting on?” the driver calls out. She’s changed his diaper the way the training course taught her and is warming the bottle in a pan of water when she hears Tom.

“I’m home,” he calls out as he does every evening. Only lately he sounds different, as if he’s afraid. “What did you do today?” he always asks, to make sure she’s staying “busy.” “It would be good if you got a job,” he keeps telling her. “Keep your mind occupied.” She is occupied. She has to fold the little clothes in the bureau, arrange the toys in the crib. “How are you?” Tom asks, coming into the kitchen. She tilts her cheek for a kiss, the way she used to. She can see the surprise in his eyes. “Honey, you look more like yourself.” He puts his arms around her. “It’s good to see. . . What’s that bottle?” “I’m warming his milk.” “Sarah! Stop this!” “Ssh, you’ll wake him.” “There isn’t any baby. You’ve got to accept that.” His voice is cracking. “We both do.” “Of course there’s a baby. He’s in the crib.” “You’re making both of us crazy.” He pulls her toward the open bedroom door. “The crib is empty, see? Oh, my God!” “Yes, God gave him back to us.” “Christ! Whose kid is it?” “Ours.” Her fingers twist the top button on his jacket. “Have I made you happy?” “Where did you…? The police will be looking for you!” Her hand moves down to the second button. “I just wanted to borrow him for a while.” “Borrow? Sarah, you can not borrow a child!” “He’s crying. Let me get to him.” Jamie never cried. “You don’t want to be in a crib, do you?” she asks, carrying the baby to the window. “What are you doing, Sarah?” “I’m showing him what the world looks like.” She holds the baby closer, kissing the fuzzy top of his head. How sweet it smells. “See the moon way up there? High diddle diddle cat and the fiddle,” she croons. But he’s crying louder. “He’s hungry, Tom. Here, hold him while I get his bottle.” “I can’t…” “Of course you can. Careful, don’t drop him.” “Drop?” His hands are shaking. “You better sit down, Tom.” “Sit?” But his arms are reaching. “I’ll get the bottle. You can sing to him.” She laughs. “Remember how we joked that you’d ruin music for Jamie if he heard you sing?” “Yeah.’” He’s staring at the baby’s face. “Hey, he’s quiet now. See what effect I have on him?” She laughs again. It’s been so long since she’s heard Tom say anything funny. “Back before you can count to a hundred and one,” she says, their old line when they didn’t want each other out of sight. The bottle’s still standing in the pan. Good thing she remembered to turn off the stove. Important when Jamie starts crawling. She hurries back to the bedroom. “Hi there, little fellow,” Tom’s murmuring. She holds out the bottle. “Do you want to feed him, Daddy?” He shakes his head, tears in his eyes. She’s never seen Tom cry, not even when the doctor told him. “Let me have him. I’ll feed him in the rocking chair.” She cradles the baby against her, holding his head up so he can drink, puts the nipple against his mouth, the way she did with the doll in the training class. He’s sucking so hungrily. She’s doing it right. “I did everything they told me to, Tom. I ate the right foods, didn’t lift heavy things.” “I know, honey.” “Tom, did Jamie…? He didn’t cry at all?” “No, honey…” “Was it my fault?”

“No, Sarah, it wasn’t anybody’s fault. Sometimes these things happen for no reason. That’s what the doctor said.” He kneels beside the chair, stroking the small head, the light brown hairs the same shade as his. “He’s got a good appetite for such a little guy.” “Like his daddy,” she says. There’s a loud knocking on the outside door. “Police! Open the door!” Tom jumps up. “How did they…? I‘ll tell them you didn’t mean…that you’re sick but the kid’s okay. “Don’t open the door! He’ll go away.” “I have to open it. Hand me the baby. I’ll give him to the police. Then maybe…” “No! That woman’s got other children. I have none.” “Police! Open up!” “None,” she cries out, clutching the baby. “Coming,” Tom shouts, hurrying to the door. The baby’s crying again, he’s lost the bottle. “You’re scared, little one, aren’t you?” “Where’s the kid?” A gruff voice. They will hurt him. She runs to the window with him. It opens with one hand. They were going to put a lock on it, keep Jamie safe. “Hush, little baby,” she sings and flies with him over the moon. She’s holding an empty blanket. “I’ll take that from you. He’s always throwing it out of the carriage.” The woman comes out of the bathroom, pulling her little boy. “Nice of you to watch him. As a matter of fact, I’m looking for a baby sitter. Three days a week. Would you be interested in the job?” Sarah looks past her where the leafless branches form a pattern against the gray sky. “You could watch him and your own kid at the same time,” the woman says. “I’m sure my baby would be fine with you. I’ll pay well.” Still, Sarah’s silent, watching the faint crescent of a moon take shape. “You better find someone else,” she says.

Vivian Lawry

The Doll

I hurried from my rented parking space toward my apartment, collar turned up, hat pulled down against the wind, moving as fast as I could go on the icy sidewalk, thankful the business trip was over. It was two o’clock in the morning. Halfway down the block, in the middle of the sidewalk, stood a baby stroller—empty. I stopped short, looked up and down the street. No one in sight. Only the glow of streetlights—and the empty stroller—shared the night with me. Drawing closer, I saw a baby on the sidewalk and bit back a scream. But it was only a doll, a doll the size of a six-month-old infant, face down on the icy concrete. She wore a black dress, white panties, and booties, a thin rainbow scarf knotted around her neck. I picked her up, and a wave of nausea hit me. She smelled like a garbage bin, and her head… Dirt and ice crystals flecked her face, neck and short, frizzled hair. Lashless, cobalt eyes the size of quarters— rimmed in black—stared at me. Her blue nose ring matched her eyes. How could plastic eyes look bloodshot? Forest green mold powdered her cheeks and titanium studs pierced her forehead, both nostrils, and her lower lip. A spike protruded from her right ear. I swallowed my rising gorge and flung the putrid mass toward the curb. But she wouldn’t let go of my hand! Was it the wind, or did she say, “It’s soooo cold.” My breath became labored; my heart hammered in my breast. I bent double and stomped on the doll’s body, trying to pull my left hand free. Excruciating pain shot up my arm. My shoulder felt like it was pulling from its socket. Whatever this doll was, I dared not to take it into my apartment. I called 911 just before I fainted. I woke in the emergency room, surrounded by people in blue scrubs and masks, hands encased in latex. The rotting garbage smell of the doll mingled with the antiseptic smells of the hospital. I blinked in the glare of the overhead lights, and the man taking my blood pressure said, “She’s awake.” A man who had been ordering others’ actions turned to me. His ID said he was Dr. Daniel Bell. “How did this happen?” “I thought I saw a baby on the sidewalk. It was this doll.” I waved my left hand, the doll still attached. “When I tried to throw it away, it… wouldn’t let go.” His eyebrows inched up. “I’d admit you to the psych ward for that sort of talk—except here you are, and there’s clearly something wrong with your hand.” I glanced at my hand, fingers and palm half-sunk into the doll’s body, then back to Dr. Bell. His gloved hand passed right through the doll as he tried to straighten my fingers. He doesn’t see her! Over the next twenty-four hours, they treated me like a cross between a sideshow freak and a laboratory specimen, never left alone, poked and prodded, stared at and talked about as if I were insensate. Dr. Bell injected IV muscle relaxants, but I continued to clutch the doll. Neurological testing revealed no apparent physical basis for what they termed my paralysis. He continued the muscle relaxants and ordered everything from massage to water baths to try to straighten my fingers. Everyone behaved as though the doll didn’t exist. When Dr. Bell ordered all manner of imaging, from X-rays to MRIs, I felt a surge of hope. But they revealed nothing. To my dismay, they showed no shadow—no telltale sign—of the doll. Was I truly going mad? On Tuesday, an orderly was wheeling me to my room when we passed a woman taking her therapy dog to the cancer ward. The dog—a beautiful brindle boxer—stopped so fast her nails skidded on the tile floor. The dog stood almost eye to eye with me in the wheelchair. She looked at my lap and sniffed, then lay down and whimpered. The woman said, “Bernie, what’s come over you? C’mon, Bernadette, heel.” The dog would not budge till we had passed and I was back in my room. No matter how the woman tugged and coaxed, the dog would not pass my door. I breathed a sigh of relief. Maybe I’m not crazy after all. Dr. Bell came in to discuss the possibility of breaking my hand and then splinting it to make the bones heal straight. “I hesitate to try that, except as a last resort. Of the two hundred and six bones in the human body, twenty-seven of those are in the hand.” He peered closely at my hand, his headlamp almost touching the doll. “When did this start?” I followed his gaze to the pale green rash inching up my wrist. I shrugged. “I hadn’t noticed it.” “I’m going to send a scraping to the lab for analysis. In the meantime, I’m ordering antiseptic baths and an antibiotic ointment.” When the rash darkened to forest green, he added an IV antibiotic cocktail. All failed, while the baths and ointment made me feel burned to the bone. I begged Dr. Bell to stop. The only good that came of these treatments was the weakening of the garbage smell. One night I thought she spoke to me, though her lips never moved: “My name is Gracie.” My heart pounded. My mother’s name was Grace—my dead mother. Another night—of course, it might have been the whispering of crepe-soled shoes in the corridor—but I thought I heard, “I need Mommy.” The words reminded me of the abandoned baby stroller. I told Dr. Bell and he initiated a police inquiry for reports of women and/or children who went missing on that night. They found nothing. I never rested easily. Awake in the night, with Gracie whispering “Mommy” into the dark, I could no longer suppress memories of Darren insisting he wasn’t father material and then leaving anyway after the abortion. I moved on. I’d come to accept—to revel in—being child-free. In the gray dawn light, I hated Gracie for dredging up all that. Three weeks later, Dr. Bell said, “Your left hand and wrist are putrefying. My advice is to treat this like cat-scratch fever: amputate to keep this—whatever it is—from advancing.” I shuddered but nodded. Just before the anesthetic dripped into my vein, I said, “What will happen to—what you take off?” “All amputations—anything with blood or several other bodily fluids, actually—is consigned to the biohazardous waste bin.”

My last thought was, how sad. I woke with Gracie in my bed. She was still clutched in my hand, and the amputated part of my arm was reattaching to my stump through the surgical dressing. When the dressing was changed, no one seemed to notice anything amiss. As the amputated part of my limb felt more solid, my upper arm became feeble and green. Dr. Bell amputated again, above the elbow. He did a third amputation at my shoulder. No matter what was done, Gracie always showed up by the time I woke, knitting my severed parts back together. I shuddered to realize that my body was no longer my own. My sisters came. I took care that Gracie was completely covered by the sheet, though I had no reason to believe they would see her. My older sister gave me a pedicure. The younger brushed my hair. She held a mirror for me to see. My eyes—ringed in black—looked huge. Orange blotched my chin. I was beginning to look like Gracie! My sisters wanted to know why I was in the hospital. I’d not given the hospital permission to discuss my treatment with anyone. I said only, “I’m in to have a growth removed.” When I declined to elaborate, they eventually stopped questioning and tried to make small talk. Their smiling lips trembled and they couldn’t seem to look at me. They didn’t stay long. That night Dr. Bell came in around midnight. Green mold was visible on the left side of my torso. I took his hand. “Is there any hope of a cure?” He shifted and cleared his throat. “One can always hope.” His eyes focused anywhere but on me. I squeezed his hand. “Then I want to be discharged. Do it as soon as possible.” “But… But…” He shook his head. “You are in no condition to leave the hospital. That’s madness. I won’t do it.” I smiled. “Then I will discharge myself against medical advice. Show me what waivers I must sign.” After half an hour of haranguing, he produced the forms. Nurses, aides, and orderlies helped me dress, gathered my things, and wheeled me to the exit. They deposited me in a taxi with a bag of surgical dressing supplies, bottles of antibiotics, and an injunction to come back daily for dressing changes. I said I would, knowing that I wouldn’t. I settled back in the taxi, my left arm and Gracie cradled in my right arm. One way or another, Gracie would have me. I wondered briefly whether anything of the old me would be left, but then I grinned and murmured, “We already look like mother and daughter. Over time, motherhood is growing on me.”

Burton Shulman

Kamikaze, 1945

Two days after the flamethrowers were done cooking the coral caves, one day after Ike and Hump had shot a film record of thousands of dead Japanese twisted across those cave floors, GIs started loading artillery and supplies back onto the ships. Ike’s unit had orders to remain on Cay-Ak another two days, ostensibly to film infantry patrols rooting out the remaining Japanese snipers who’d so far declined to surrender, but mostly because the brass hadn’t worked out their next deployment. At the moment, Ike sat on the hood of a jeep with Hump, killing time ritually, running through inventories of the anatomical highlights of various Hollywood bombshells. Hump’s head flopped forward in a mock-swoon. This was mildly amusing until it started sliding down Ike’s chest and came to rest in his lap. Ike told him to cut it out. Hump didn’t move; Ike asked him loudly what the fuck he was doing. That was when he noticed that his own fatigues were darkening, saw a hole in Hump’s forehead, and became one of the guys the medics had to jab full of morphine and drag off to a field hospital to stop the screaming. After the morphine, the medics didn’t notice that Ike’s eyes were empty; anyway, they didn’t mention it. Within a few weeks, he passed the reflex tests and was able to speak more-or-less normally. He no longer sobbed before answering questions. Saying his name, the name of the current President, where he was, what had happened to him, convinced the docs to let him return to his unit. The docs were eager to get rid of anyone they could, as quickly as possible. Ike knew he was now crazy, but suspected he wasn’t going to stay that way. He felt that the fastest way to recover was to get back in the field. Hump was the main reason he felt that way; he kept admonishing Ike to get off his ass and go back to doing what he did. Ike didn’t tell the medics about Hump’s pep-talks; Hump pointed out that it wouldn’t help his case if he explained that he himself, Hump, had taken up residence in the middle of Ike’s brain. A few weeks later, the General, General MacArthur, took them back to the Philippines. Ike’s unit had the honor of filming the Supreme Commander splashing around in the surf, chewing his corncob pipe, and reciting his horseshit. Two years earlier, when he’d abandoned the Philippines, some PR boys made him famous with the quote: “I shall return.” Ike found it amazing how one line had papered over such massive tactical fuckups. The General liked it so much that he now wanted to be sure everyone in the world knew that he’d kept the promise he’d never made. He kept repeating it, “I have returned, I have returned,” muttering it even when he thought no-one else could hear. At those times, with Ike eavesdropping, the General sounded surprised. He was a terrible actor. They had to shoot him from every angle to ensure that somewhere amid all that footage, he looked convincing for a few seconds. Ike also filmed the survivors of the Bataan death march, as they were liberated from the Japanese camps. Two years earlier, at the end of a chaotic battle, MacArthur had abandoned them to a Japanese forcedmarch that lasted eight days and covered sixty-five miles with barely any food or water. The public reason for this betrayal was a direct order from the President to leave. Few believed this. A surviving journalist printed a parody of “Battle Hymn of the Republic” that he said some of them had sung: Dugout Doug MacArthur lies a-shakin’ on the Rock Safe from all the bombers and from any sudden shock. Dugout Doug is eating of the best food on Bataan And his troops go starving on. Another wrote a poem that one of Ike’s buddies read out loud: We’re the battling Bastards of Bataan. No mama, no papa, and no Uncle Sam. No aunts, no uncles, no nephews, no nieces, No rifles, no planes or artillery pieces, And nobody gives a damn. Reports of what had happened to them in these camps. Ike struggled not to think about them. Blinking in the white sunlight, they seemed more interested in chocolate than freedom. They hardly acknowledged they’d been liberated at all. MacArthur insisted on repeated shots of himself shaking skeletal hands. Ike made sure to catch their winces as the General blessed them with his famous grip, ignoring the fact that it caused many of them pain. The General ignored things like that unless he was trying to work up a teary-eyed oath, or display the humble gratitude of a great commander. Ike caught a few GIs staring at his noble Roman profile with enough hatred in their eyes to melt him into the cracks in the earth. The General ignored that too. The problem wasn’t that the man had abandoned his troops. It was that he should have come back crawling, tearing his clothes off the way his heroes in the Iliad would have, begging their forgiveness—not for having left them but for having let himself go on living so well, knowing they were back here starving to death, mostly because of him. His phony vow shouldn’t have been to return but to never stop repenting. It was regular grunts like these who made it possible for assholes like the General to go on with their death-dealing. He should give one of them a gun and let him decide whether or not to blow his head off. Instead he walked around imperiously, followed by cameramen filming his victory parade. Whenever Ike got the chance, he swung his camera around to shoot the GIs reactions to him. He knew this wouldn’t make it into any newsreels but it made him feel better. He wondered if any promise kept had ever meant less to those to whom it had allegedly been made. The GIs looked eerily similar to the Japanese who had surrendered after weeks of starving in the Cay-Ak caves. They were like walking dead. The difference was that where the Japs’ eyes had most often seemed empty or terrified, the eyes of the GIs were full of hate. During his two-and-a-half years in and around combat, Ike had managed to stay free of nightmares. Hepatitis, malaria, and dysentery brought hallucinations, but even the hallucinations were relatively benign. When his unit was ordered onto a destroyer in a 3rd Fleet convoy headed, rumor had it, for the Japanese homeland, panicked dreams started chewing him up as if they’d been sharpening their teeth. Hump became his child, his mother, an old man. Shocking him awake nearly every night was a dream of falling into a hole stuffed with dead Humps, hands reaching for him as Ike lay paralyzed. Sometimes he’d drag himself awake and lie sweating in the dark, trying to slow his heartbeat. Other times he’d be shaken awake by one of his buddies, who hissed that though Ike was now the senior shithead in the unit, if he didn’t stop yelling they’d get him Section 8’ed out so the rest of them wouldn’t go as crazy as he was. Another rumor came down: the convoy was going to hit Japan itself, in advance of the full invasion. The ocean war was almost over; island combat would shift to street fighting—but not the kind they’d heard stories about from Europe. No, in this case—guys kept saying it to each other, as if hoping one of them would deny it—they’d be killing more civilians than soldiers. Why? Because the civilians would be trying to kill them. He’d always taken secret pride in the knowledge that for all the combat he’d witnessed, he himself had never fired a single shot in anger. He was sure he’d never killed anyone. One morning his unit received their new orders: they were being redeployed as common infantry. They’d only pull out their cameras when there were breaks in the fighting. About this, Hump was silent. Japanese Zeroes were no longer bombers but bombs—kamikazes, suicides. Pilots were chained into cockpits, their planes packed with bombs and flammable chemicals. Fuel was in short supply, so they were only given enough for a one-way trip. Ike wondered if they considered themselves corpses even before they took off. There could be something calming about that. But what did a breathing corpse feel like? Since Cay-Ak he sort of thought he knew, but wasn’t sure. The only open question about a kamikaze pilot’s future was whether his body would blow apart or drown—whether he’d hit a ship full of GIs or an ocean swell that would swallow him without a trace. When the sirens went off, Ike was fighting to keep his attention inside the IMO’s viewfinder and stop shaking each time one of the battleships fired another round at a group of Japanese ships. But sirens were bad. He tucked the IMO under his arm and raced for the ladders to get below. As he started down, though, he glanced up just as a Zero slammed into a neighboring ship and blew apart, opening a crippling hole in the destroyer’s side. Inexplicably, his panic vanished. He stopped, and watched himself crank up the IMO then start back up the ladder against the rush of fleeing bodies. The problem, he saw later, was that in the course of his ongoing mental conversation with Hump, he forgot that Hump wasn’t exactly there anymore. Had he been, he’d have screamed at Ike and shoved him back down the steps. When that didn’t happen, it seemed as if Hump was, in effect, ordering him to go back and shoot. So that’s what he did. Shooting, after all, was his only relief. At first, he focused the IMO on the GIs leaping off the thirty-foot deck of the other ship, landing in open ocean that moved up and down, patchy with flaming oil and wreckage. A bee-like hum spun him around; a Kamikaze was coming for Ike’s own ship. Hump spoke, suggesting—reasonably, Ike thought—that since he was already here, he might as well get the best shot he could. To do so he had to move toward, not away from, the Zero. Everything in his mind was working perfectly except his sanity; he estimated maybe twenty seconds to set up as he looked around for the best angle. He decided that if he wrapped his legs around the gunwale, he’d have a good vantage point and his hands would be free. A voice that wasn’t Hump’s asked him why he was doing this. He chose not to address the question. He adjusted the IMO’s aperture to accommodate the midday sun, and while climbing onto the gunwale, managed to start shooting, trying to hold the Zero in the shot by keeping one eye on it and the other in the viewfinder. He achieved a rhythm of refocusing and readjusting aperture and angle in almost continuous motion, capturing the Zero’s progress toward Ike’s annihilation. When it entered its dive, Ike was momentarily paralyzed; that’s when Hump changed his mind and said that maybe it was time to get below. The Zero’s forward machine guns were now spitting at him, as his ship rode the swells. Working out of reflex, Ike was mostly able to hold the guns in the center of the frame. It occurred to him that the only way this was possible was if he himself, standing alone on the deck, had become the pilot’s focal target. If that were the case, each would be the last person the other would see. Ike considered this with psychotic detachment; the brass was going to love the footage as long as the IMO itself didn’t get hit. He saw that he was killing himself exactly as the pilot was, and realized he now knew how Kamikaze pilots felt when they took off. One part of their minds was shrieking, “Run!” though it was clear that they wouldn’t. At which point the other part went into a deep sleep. Ike suspected that part might include the conscience, but he wasn’t sure.

He regretted the fact that he wouldn’t be able to tell anybody this. Hump seemed to understand. Just before impact he saw the pilot’s face; this close he could see that the pilot wasn’t looking back because he was already dead, cut apart by bullets from Ike’s ship. Ike had the impression the man’s mouth was open, and while it was possible the last thing he’d screamed was Banzai, it seemed far more likely that it was Mama. The word “Mama” awoke Ike’s sleeping mind just enough so he himself now screamed “Mama” before an unexpected shell slammed into the Zero’s fuselage, shoving it sideways and causing a wingtip to bend down just enough to touch the ocean. The plane spun into a half-cartwheel, slammed sideways into a swell, and blew apart fifty yards to starboard. The concussion nearly pitched Ike overboard, but somehow his legs held on as razors of shrapnel hissed by, faster than machine-gun bullets. One sliced open his arm, which felt, at first, like a light touch. The rest sliced into the deck and the ocean, sizzling metal accompanied, no doubt, by bits of the pilot’s flesh and bone and—who knew?—memories and emotions. Ike was told later that he’d continued to crank the IMO long after the attack was over, and the film spent. A sailor emerging from below heard strange, consonant-less wails. He said it took some doing to pry Ike from the gunwale and get him down to sickbay. This time, his not-so-temporary insanity won him a Bronze Star. The CO also took the occasion to nominate him for a Silver Star for extreme bravery under fire. Decades later he would insist to his son that he’d simply gone mad. None of the combat footage he shot in later decades came close in risk; on this one occasion he’d been suicidal. In the field, looking through your camera sometimes made you act bravely because you felt as if you weren’t where you were. On the other hand, one of the few positive effects of his time in combat was to teach him to find ways to tolerate, even appreciate, wherever he was at a given moment, rather than always wish he was someplace else, as he had for most of his life ‘til then. Once again, though, Ike surprised himself with something like resilience. Within a few days he felt well enough to fake that he was well enough to be released from sickbay. He kept apart from the others, instead engaging in marathon conversations with Hump. The hopeful part was that he was rarely unaware that he was crazy, and fully understood that Hump was dead. He chose not to worry because he would soon be dead himself. Shooting was the only reason he’d ever found for living, so it didn’t seem so crazy to be willing to die as long as he could keep shooting till the end. Because, for the most part, he now thought of himself as already dead, he was no longer all that afraid. He no longer cared about anything at all, which, under the circumstances seemed to him quite sane. Late morning on August 6th, 1945, the ship’s company was ordered on deck. The captain seemed subdued. He announced that he’d received a communiqué explaining that a few hours earlier, a U.S. plane had dropped a new kind of bomb on an industrial city in Japan. The communiqué promised more detail was forthcoming. For now, it said that a single bomb had destroyed an entire city. The captain, who looked to be in his forties, showed none of the queasy thrill that Ike himself started to feel. He simply made the announcement and dismissed them. Ike’s reaction mirrored that of most of the men around him: he started shaking with hope. Despite everything, he discovered, he still wanted to live. A few days later they were assembled on deck again: another bomb, another Japanese city. Then, several days later, against every shred of prior evidence that such a thing was possible, Hirohito surrendered unconditionally. Ike screamed himself voiceless, along with everyone else. No one was saying how many civilians had died. But forever after, Truman’s decision to drop those bombs seemed to Ike wise beyond measure. He was certain that if that group of civilians hadn’t burned and died, millions more would have, along with GIs including Ike himself, in vicious, close combat. Whatever else they’d done, those bombs had saved his life. But as the euphoria faded, he faced a new crisis: he hadn’t counted on having to fill up another forty-odd years of living. The thought of redirecting his energies yet again, this time back toward the laborious business of building a life, was exhausting. He was glad to be alive. He wasn’t sure about having to live.

CREATIVE NONFICTION

Danielle McDermott

Familial Paper Trail

Photograph of Dad’s family

One December morning, I lied to my dad. I asked to stay home from school, giving some garbage excuse about a hurt stomach. Dad’s eyes were pink-ringed and heavy. I noticed the quivering of withheld tears, and I couldn’t understand why he was upset. He placed his large calloused hand on my forehead. I dreaded he’d figure me out and drag me to school. I hated third grade because of my teacher who bullied her students. I’d considered running full-speed on black ice to try and bust up my leg.

At nine years old, I believed that my pain tolerance was exceptional. It wouldn’t be the first time I’d done something drastic—

once I’d locked myself in the gym’s storage room for an hour before someone realized I was missing. Mom was furious, but Dad had convinced her not to punish me. They already knew about that teacher. She’d targeted my brother two years before.

Patrick would come home each day on the verge of a meltdown— crusted snot stains on his shirt, face peppered with dried jagged tear trails, enflamed oozing scabs where he’d carved gorges into his dark, tan skin.

Maybe Dad’s empathy persuaded him to let me stay home. Dad moved his hand away, scrutinizing me with his shiny wet eyes. I wanted to ask if he was about to cry. Is a kid allowed to ask an adult that question? He left to call the school. Sticky slingshot hands dripped from the ceiling.

Most were adhered on the window to cast a kaleidoscope pattern on the walls. I wasn’t allowed messy goo or Play-Doh anymore; I kept losing the stuff in the carpets. Mom tolerated the sticky hands, but just barely. They started to peel off the ceiling. How long would an actually-sick person stay in bed before moving to play Spyro on the GameCube? I heard a muffled sob and wondered if I should find who was crying.

Opening my door, I snuck down the stairs the best way I knew how—exactly like Scooby and Shaggy—and stopped where the wall changed into a twisted metal railing. My dad was on the couch, his shaky hands clinging to a large photo, the black Document Box laid open like a discarded Muppet. His broad shoulders blocked my view of its details. I weaseled under his arm to hug him even though his tears upset me.

He had pulled splinters and glass out of my feet—scrubbing salt on the entry point while his kid shredded her voice raw wasn’t a fond memory, but he still did it. The trade was fair.

The picture’s edges were worried into tattered softness and rounded corners. Two adults and three boys sat together in a restaurant. The discoloration distorted the distinction of each person’s face. I could figure out which was Papa, the cigar between his fingers faded into red pastel. I had a hard time telling which child was Dad. I didn’t know the woman in the photo with dark hair. I knew Papa’s wife was Nonna, so who was she?

The only similarity Nonna and her shared was their pale skin. Nonna has blonde hair, blue-green eyes, a shorter face. The unknown woman was Grandma Pat. She was Dad’s mom. She was his Wonder Woman who took care of a big house and four kids while her three boys rotated through the emergency room in Connecticut. Grandma Pat was amazing and wasn’t to be messed with. Dad loved her. Tears started to navigate over his textured skin. Dad didn’t shake this time; his eyes stayed focused on the faded still of Grandma Pat. He, at twenty years old, came home from his college’s final exams. He went into the bathroom. She was already in there. She sat rigid and slumped over, wide-eyed, dull-lipped—a burnt-out cigarette inches away from the bathroom rug. He closed the door and apologized, thinking she was using the toilet. A few minutes went by before he registered what was behind the door.

Missing Files

In seventh-grade science, I learned about space. My assigned project was to track the constellations and the moon’s phases across the October sky. The orange-polluted darkness of Pottstown blotted out the weak stars of Pegasus. I relocated the Document Box onto the roof, flashlight in hand and homework discarded. The gray handle was cracked, the black top a gradient of dark gray and brown, and a busted up clasp. Dad put all the important paperwork, photos, and mementos into it. I made sure to wipe the smudgy slick dust onto my plaid uniform skirt before touching

Dad’s white yearbook.

I was enthralled with the grayscale photos of his high school yearbook that showed pictures of a person who was simultaneously my dad yet not—a version of him with his mom before his car accident and without me. I wondered about Mom’s yearbook. Nothing of hers was there.

No childhood photos or the drawings that Grandma talked about, not even adult photos or birthday cards. Only her brutalized birth certificate, wedged inside a blank envelope alongside mine, Dad’s, and Patrick’s. Her certificate was black, but the yellow of the heavy paper slipped through, crumbling edges worn into velvet, a hole eroded into the center from years of folding and unfolding.

A father’s name wasn’t there, and I knew Mom was beaten for it by her stepfather. She told me of the anger that came her way if the remote

wasn’t where he left it, if Mom stayed in her room too long, if she didn’t come out often enough. Grandma would have darker spots on her deep brown body if she tried to stop him.

“Bruises on black skin are easy to miss unless you know what you’re looking at,” Mom told me.

Did Mom keep her mementos elsewhere? She most likely would have kept them separate and scattered throughout the blue storage bins oriented into our two-bedroom apartment. I wasn’t allowed in her boxes; no one was. She would yell at us, fearful that we’d throw all her things away.

When Mom came home from her double shift at the deli, I asked her about her yearbook. “I never got one. No one’ve signed it anyway. I told you about those girls who tried to get me raped, right?” Maybe she’d have her drawings instead. Grandma told me whenever

we visited about her charcoal and pencil drawings of the insects she collected to sketch their minuscule details.

“It all got tossed out. Why are you asking me about all this, Bee?”

All her artwork got shredded and thrown away by her stepfather when she married Dad. Her stepfather wasn’t fond of him—a sentiment nearly all of my mom’s family shared since my dad’s white. I knew my baby album had been destroyed in the same flood that had ruined her high school diploma. She must’ve had some of her childhood pictures, like Dad’s photo of him at the Woodway Beach Club or the one

of his mom looked at every December. I considered asking about her new Rune Factory farming game instead. If I pushed too much, she’d leave me and cocoon in her fuzzy brown blanket, the “M” in her brow the last thing I’d see of her for the night. I wanted to know about the photos and risked setting her off.

“Your grandmother has all those pictures. I’ve always been ugly, anyway. Praise God that you have such beautiful curls instead of my nappy

rats’ nest. You and Patrick were such cute babies. Do you want to see your pictures? They’re in my wallet.” The only photos of her as a kid are the ones in Grandma’s house, each framed in silver etched with crosses and doves. Every bit of Grandma’s small townhouse spills with frames, cat figurines, and smooshy furniture smelling of sweet pimento and sharp ginger root. The photo I see the most is the one I have the hardest time looking at. It sits in the middle of the coffee table, completely unavoidable since the couch is the only open sitting spot.

The photo shows Mom as a child in a white blouse with a rounded collar. She sports two thick braids, each tied off with red hair ties. Her right cheek and neck are darker than the rest of her. Mom wasn’t exaggerating—you can only spot the bruises if you know what you’re looking at.

Copy of the Individualized Education Program (IEP) Packet

I stopped enjoying school around the first grade. Running around the playground was boring—the swings were always taken, and my classmates’ shrill voices overwhelmed me. Halfway through the year, I met the second-grade teacher who taught my brother. Rather than going to recess, I helped her prepare for the afternoon activities. I was more than happy to use the squishy sponge to clean the blackboards. The dried tracks left behind by the imperfect sponge were more interesting. I preferred the muffled claps of the erasers that billowed out chalk clouds.

The second-grade teacher asked me about Patrick, wondering whether he liked third grade and which subject was his favorite. I lied to her.

She’d be hurt to know how his new teacher treated him, the verbal abuse he received and the comments about his appearance. Who would believe me, some first-grader, anyway? She asked if Patrick was getting the help he needed. I didn’t understand. I just wanted to be useful.

Patrick was first misdiagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) a month before entering third grade. He was later re-diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome, a subtype of Autism. His second grade teacher recognized Patrick would begin to talk at random and

speak “at length about topics unrelated to the [class] discussion.”

Being my oftentimes only friend, the unrelated comments were normal.

He liked to teach me things, like puzzles and magic tricks. When playing Super Mario 64, he’d start off silent, totally immersed as he controlled a blocky Mario to solve and teach me the game’s puzzles. Patrick would start talking about different types of birds and the purposes of their different beaks.

Patrick plays mostly shooter-type games now, which I’m too anxious to play. I’m the “panic and use all the ammo” type, or as my dad says, the “spray and pray” player. Patrick isn’t willing to show me the controls. Granted, I prefer puzzle or story-driven games that we used to play together but that he now finds boring. In middle school, he taught me how to solve 3D puzzles shapes. I liked the pyramid the most, not only

because of its color but the simplicity of its shape. The clear yellow-tinted pieces click together to form a semi-transparent pyramid, every division line white and opaque. It was obscenely difficult to put together, but he helped me as we talked about ancient Egypt and ancient gods.

Oftentimes, he’ll struggle with the shapes of words. The counselor noted in the IEP that he “often stumbled over what he was trying to say.”

Patrick still does, and coupled with Dad’s dyslexia, I’m accustomed to offering words or tail-ends of sentences. I noted the pattern to Patrick.

His brows came together like Mom’s “M” as he asked, “Do you hate me because you do that?”

Patrick often asks how we feel about him—he’s not able to read people’s body language or emotions, especially not complex ones like frustration. After his diagnosis with Asperger’s, Dad had to choose between his career and health or becoming Patrick’s primary caretaker. The other option was to send Patrick away, which Dad couldn’t bring himself to do. When asked how Dad could sacrifice so much, he establishes a jocular manner while he shrugs—how could he send his son away? Dad had tried to kill himself when he had been sent away—failing only because the donator of the gun lied about it being loaded. He didn’t want Patrick to experience that hopelessness.

A middle school teacher remarked in the IEP that Patrick has “juvenile-almost-like temper tantrums.” If communication falls apart during an argument (usually between him and Dad), Patrick will grasp fistfuls of his pillowy black curls while doubling over, screams vibrating in his

throat while strips of spit dribble from his mouth.

“You hate me because of what you gave up! You’d all be happier if I just went away or died! None of you would care if I just killed myself!” My position in our family was the peacemaker. I’m told that I understand Patrick’s spoken and unspoken language the most. Even the IEP mentions me in the “Parent Input and Concerns,” not by name but as “sister” who “helped organize him.” He needs the reminders since he

doesn’t have a routine; he says it’s too hard and already has one. When I point out the inconsistencies, I’m accused of believing he’s a bad person. Once, I offered to play Diablo 3 with him to avoid a confrontation. He wanted to ask Mom and Dad to play. I tried to stop him.

There’s usually an argument if Patrick plays—Mom hangs around the safe area too much, Dad’s hack-and-slash Barbarian character clashes

with Patrick’s shoot-and-bolt Demon Hunter, and I like to explore for all the in-game loot while he speeds ahead. He asked why I didn’t want our parents to join in. I tried not to answer; I initiated a boss fight as a distraction and outright lied. He asked again, and I chose the least likely solution. I told him the truth.

“So you all hate me, right? Can’t even play with me without having a problem. I’m just a problem to you! You’d be happier if I was never born.” I don’t hate him. I don’t think I ever could, but I told him I was done, exhausted of always being yelled at, of being attacked whenever performing my role. He screamed at me. He scrunched his face together, his voice pitching higher, telling me that I couldn’t be done; I’m his sister. How could I do this to him?

“So you really do hate me? You’ve been lying all these years, huh? I’m just something you can throw away!”

I’m tired of being asked if I hate him. Why does he keep asking when my answer never changes?

“Because I don’t believe you.”

His distrust is fair. I offered him a lie as my escape. Now instead of mediating, I watch for the warning signs, emerging to see the aftermath. Dad laughs about his growing fear of Patrick despising him. Mom’s flees to her bedroom and blankets when Patrick comes home. When the shouting starts, I think about the puzzle pyramid. I recall our discussion of the history, Yu-Gi-Oh, the structural integrity of pyramids, the friendship we had. He didn’t notice the puzzle was missing. I’ve decided to keep it for myself; it wouldn’t fit into the Document Box anyway.

Ariella Neulander

No Child’s Play

I. Balance Beam

Strokes, like voracious Pac-Men, have chomped through huge swathes of my mother’s brain. Now my once-articulate, super-competent mom can barely feed, wash, dress, or explain herself. Aides help her do everything she forgot how to do for herself; doctors keep watch over her

heart and brain; my sibs visit when they can; and my still-working dad brings home love poems and roses, along with a web of anxieties, expectations, and demands.

I am local and retired, so I referee. I was a lawyer in my former life. A career as a tightrope walker would have been better preparation. The aides want a predictable schedule and salary. My mom likes them; we all rely on them; I want to keep them happy. My dad resents them. He cancels or sends them home without notice when he is off work or home early, then docks their pay. I cajole; I argue; I attempt to take control. My father stomps his feet and digs in his heels. A favorite aide threatens to quit. My mother needs her meds. She also needs her autonomy and self-respect.

We put her pills in front of her before dinner, but after dinner, they are still there. We remind her; the pills remain untouched. So we hand

them to her. “Stop that; I’ll do it myself!” she says. The big hand on the clock makes another orbit and the meds are just where we put them. Soon it will be time for bed. “She won’t take her pills!” my father shouts, banging the table. She can’t take her pills, I think. “I’ll do it; just leave me alone,” pleads my mother.

The cardiologist says we should lower my mom’s blood pressure to prevent another stroke. The geriatrician says we should raise it to keep the blood flowing to the brain. The neurologist says a baby aspirin each day could help. The cardiologist says, “Too dangerous.” My mother says she doesn’t feel safe spending weekends alone with my dad. My father says he can take care of her alone. “Please!” he screams.

“I can’t stand this! Strangers in my house around the clock! I am going to go crazy!” My mom is a frail reed and my dad a ticking bomb. My big sister says, “Have you checked into this? Have you considered that? Did you ask her this? Did you tell him that?”

My little sister says, “Stop with the obsessing already. There’s only so much we can do.” My father says, “Make her eat. Make her drink. Make her wake up and walk with me outside.” My brother, from six time zones away, says, “You’re amazing; thank you.” My friend says, “Has it occurred to you that maybe your mother wants to die?”

II. Merry-Go-Round

My mother had three more strokes at home last week. I was with her after each one. Zach and Becky, my son and daughter-in-law, asked if I could still babysit Monday. “I hope so,” I said. “But this end stage of Grandma’s life reminds me of the end stages of Becky’s pregnancy. It’s difficult to plan. You never know when that big event will come that will change everything.” My granddaughter, Aria, is now one year old. She uses the bars of her crib, the seat of the couch, or the top of the coffee table to pull herself up to stand. She does this over and over again, every hour of the day. I remember when Zach first did this at the Danish modern wall unit in the living room of our garden apartment. He kept his Thumbkin Fisher-Price people there. Soon, he’d put them on the turntable of our record player and spin them around as if they were on a merry-go-round. My mother can’t always pull herself up to a standing position anymore, even if we place her hands on the arms of the dining chair. When she does manage it, the effort can take her an hour.

Aria is starting to talk in two languages. She says “duck-a-duck-adoo” and we do not understand. She is also saying words that we do

understand. “Bebe,” she says, for baby. “Elmo.” “Agua.”

My mother is quieter than ever. When she speaks, we often do not understand. She is forgetting her words. Soon, I fear, she will be down to

three, like Aria. Or none at all. Aria helps us dress her in the morning. She knows that the shoes go on her feet and the hat on her head.

Until recently, my mother dressed herself. But when she tried to put her legs into the sleeves of her sweater and her arms in her pants, the

aides had to step in and help. Aria found her cousin’s carriage yesterday and, grasping it, took her first few steps. Soon she may give up her stroller.

My mother almost tottered yesterday until we brought the walker for her to grasp. Soon she may need a wheelchair.

Aria eats with her hands. She has a hearty appetite. She loves to slurp up milk from a bottle, drink water from a sippy cup, and sometimes, still, nurse from her mother’s breast. My mother eats with her hands. She has almost no appetite. She can look at a half-cup of juice placed in front of her for most of the afternoon without touching it to her lips. Aria makes in her diaper. So does my mother. Aria claps hands for me. My mother practiced clapping hands last week with her exercise teacher. Aria sleeps eleven hours at night and takes two naps during the day. My mother sleeps eleven hours at night and sometimes most of the day. Aria’s smiles are broad, her laughter unbridled, her mirth overflowing and infectious. I play peek-a-boo with her, as I did long ago with Zach and then his little sister, and she giggles. She lights up every room she enters.

My mother’s smiles are fleeting, and her laughs few and restrained. Sometimes, as I look at her, she seems to disappear behind an invisible screen. But each moment of connection and joy reflected on her face stabs my heart with a sharp sliver of light.

III. Seesaw

It has been four weeks since my mother’s last three strokes. In the hours following each one, she could not sit or stand. She did not want to

speak or eat. She stared blankly into space. She cannot possibly recover this time, I thought. I need to prepare myself. I need to prepare my siblings, my children, and, most importantly, my dad. Then she recovered. She sat and stood on her own. She spoke with friends and relatives on the phone. She took a long walk around the neighborhood and accompanied my dad to a concert. She smiled when she saw me. She laughed when I cracked a joke. She asked about my novel and my husband’s tooth pain. I felt awful for killing her off in my mind.

A week ago, my mother couldn’t figure out how to climb the three stairs to her bedroom. Then getting up from a chair or bed, once again,

became too hard. By Mother’s Day, she had no interest in gifts, cards, or greetings, let alone the brunch and chocolates we had brought to share.

She had a few spoons of soup her aide fed her. Otherwise, she did not eat. She said nothing all day. And I did not see her smile even once. I spoke with my father. I wrote my siblings and children. I began thinking about a eulogy. Last night, my mother fed herself four scrambled eggs with a fork. She laughed at my father’s joke. When he sang, “Here comes the bride, all dressed in white,” she corrected him. “I’m wearing blue,” she said. Maybe she will bounce back after all, I thought. But today, she is barely opening her eyes.

IV. Peek-a-Boo

My mom could always see the real me, even when I tried to hide it behind a mask. She was like that with everyone. She got the gist of people

immediately. And she could read emotions swathed in any number of defenses and disguises. Now my mother is lying, or more accurately dying, in the hospital bed that hospice delivered three weeks ago. I am watching her closely, mostly to be sure she is still breathing. But I am not sure I am seeing her. Here is what I do see. My still beautiful, elegant, uncomplaining mother in an adjustable metal-railed bed by the window with a pillow wedged under one hip, another under her shins, and one under each elbow to keep her from developing bedsores. She has barely eaten in weeks and has not even had her typical half-cup of ice chips in days, so her belly is shrunken and her cheeks, wrists, and ankles are sunken. Her hands and feet are growing ever more mottled and purple while the formerly peach tinge of her chin and the rosy-pink hue of her lower lip are bleaching out to a single, eerie grayish-white. Her lovely white hair, which my sister washed in bed for her last week, is now mussed despite my effort just an hour ago to brush it into place. Her eyes are closed and her mouth wide open. She is panting fast and hard one minute, and the next, I cannot tell if she is breathing at all.

That is now. About a month ago, when my mother was still sharing a queen-sized bed with my father, she was transported one evening into a frantic, waking nightmare. She told my dad that she saw a baby alone in an abandoned house. She cautioned me that my granddaughter, Aria, was about to fall and that I had to tell my son to catch her, quick. And she insisted to her overnight aide, throughout the night, that there was a baby stuck in traffic. “Over there,” she said, pointing urgently to the closet. Then, without warning, when the aide stepped away, my mother leaped out of bed, bounded to the closet, and fell on her backside. “I thought I saw a baby there,” she told me, puzzled, the next morning when she returned to our world. “But maybe I didn’t.” A week or two ago, alone now in her hospital bed, my mother once again floated away. We could not tell if she was merely in a long, deep sleep, or if she was heading toward a coma or death. We were just grateful that this time she was calm.