TABLE OF CONTENTS

Issue 17

Boggs Curry Fiction Contest Winners

Chital Mehta – First Place

Damaged Gifts

View .PDF

William Luvaas – Runner-Up

It Runs in the Family

View .PDF

Fiction

Dante DelBene

Estuary

Alfredo Salvatore Arcilesi

Pasture Statues

Troy Pottgen

Happy Hunting

Douglas Steward

Electronic Alchemy

Lenny Levine

What’s in a Name?

Jon Fotch

Bumblebee

Ashley Anderson

Zipper Pulls

Mark Pearce

The Ultimate Christmas Story

John Fretts

Cellar

Robert Granader

Are You My Son?

Maria Wickens

Gangster of Love

Poetry

Sandra Newton

Permanence

Richard T. Rauch

Worth a Lyric

J. Tarwood

When Rain Falls

Rick Kuenning

Things to Love

Sandra Newton

Nothing Lasts Forever

George HS Singer

Training For You

Emma DePanise

Northern Flicker

Anne Dyer Stuart

Facts at Thirteen

George HS Singer

Setting, Salving

Umiemah Farrukh

what is a friend?

Peter Money

A Tree, You Know

Umiemah Farrukh

Merisda

Megan McCormick

A Shape

J. R. Forman

robin

Barbara Schweitzer

Perfect Exchange

Margaret B. Ingraham

On Daylight Savings

Laine Derr

Wild Primrose

Margot Wizansky

Pierogies

Megan McCormick

Sayable Things

Joseph D. Milosch

Rim of Darkness

Rick Kuenning

Monotheist

Kasha Martin Gauthier

Suburban Scarlett

Robin Reagler

Perhaps

The Thread

Ricardo Moran

It Felt Like a Wednesday

Caleb Coy

Remedy For My Mind

Stephen J. Dempsey, Jr.

Of Your Memory

Eric Machan Howd

Through Screens

Mary Warren Foulk

September Survival

J. Scott Price

Crickets

Paula C. Brancato

The Dark

Matt Schumacher

The Scarecrows on Old Mill Road

George HS Singer

Ernestine’s Color Wheel

Allen Strous

Cauldron

Mark Brazaitis

Ice

A Lake in Michigan

Marte Carlock

Painting the Window Sill

Bertha Rogers

No More

Bruce E. Whitacre

Good Housekeeping

Doug Bolling

Where We Are

Paul Hostovsky

The Curiosity Factor

Paul Hostovsky

The Story of the World

Susan Sonde

A Tragedy’s Brewing

Lee Peterson

Cases of Disease

Susan Sonde

Exiles in Winter

Victoria Ketterer

Hometown

Emma DePanise

Pitch

J. Scott Price

Seeking Something

Rand Cardwell

Little Tree

Mikal Wix

Sleepwalking Through E-Block

Robin Reagler

The Dead Stalk Us

Lee Clark Zumpe

indigo blue

Bertha Rogers

Spring and All That

Umiemah Farrukh

Anxiety in My Mind

Hannah Jane Weber

Pancakes

Barbara Schweitzer

The Sweetness Is

Creative Nonfiction

Tamara Adelman

Carson

Kelsey Brogan Fiander-Carr

Don’t Eat, Then

Darius Brown

Interview with Deesha Philyaw

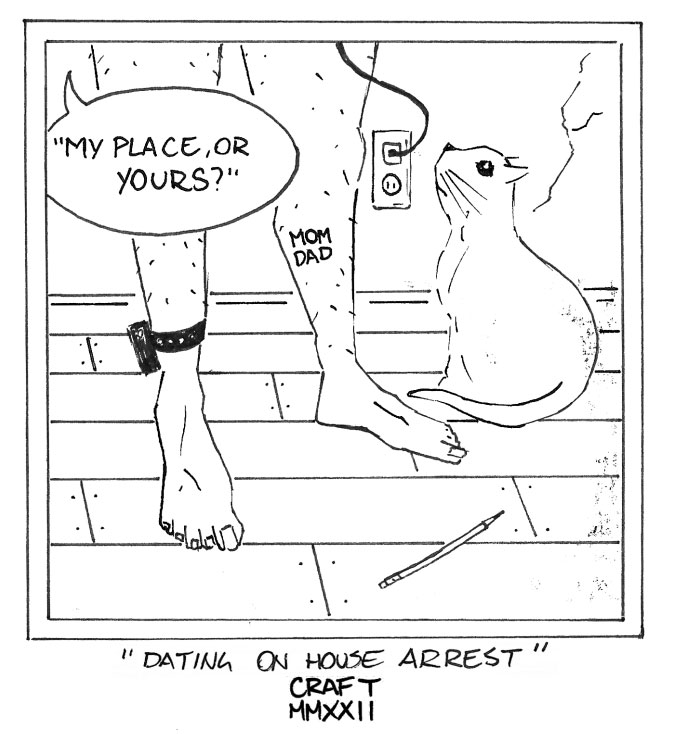

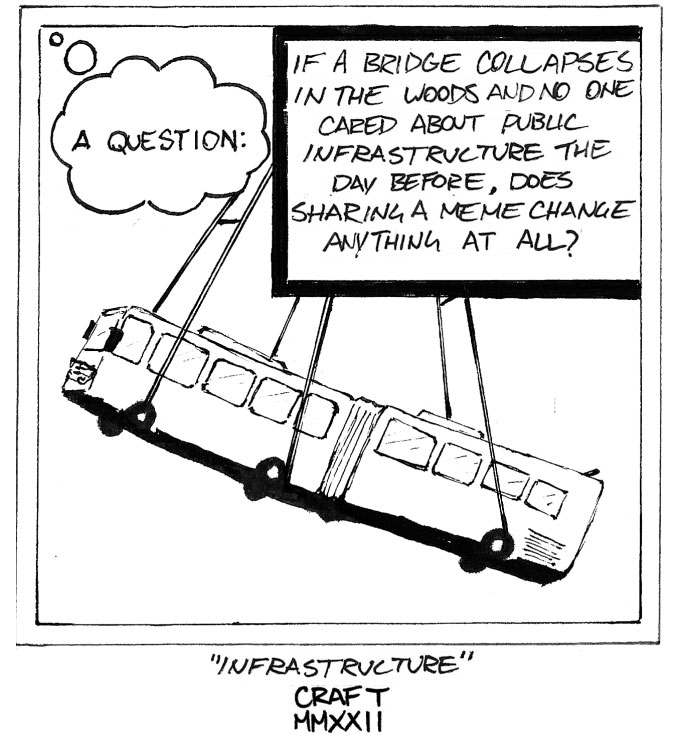

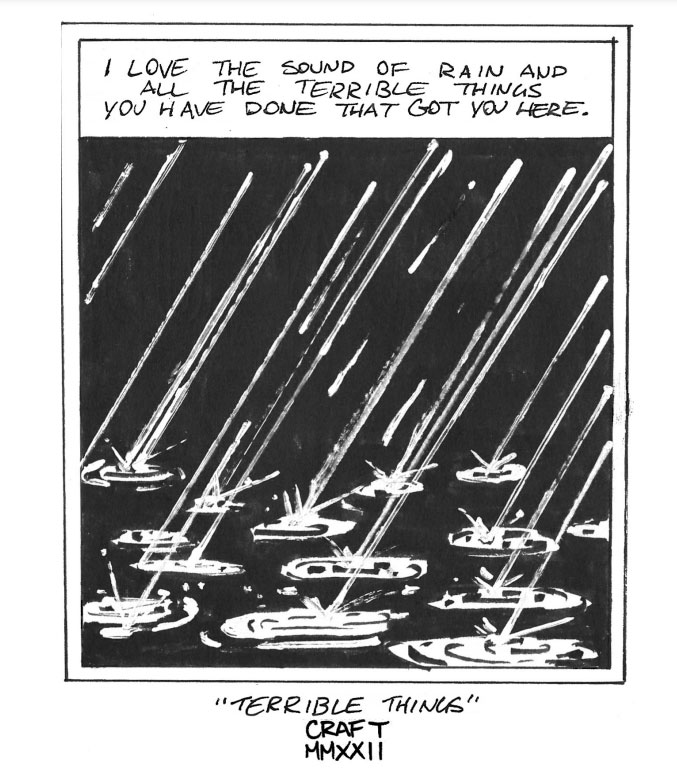

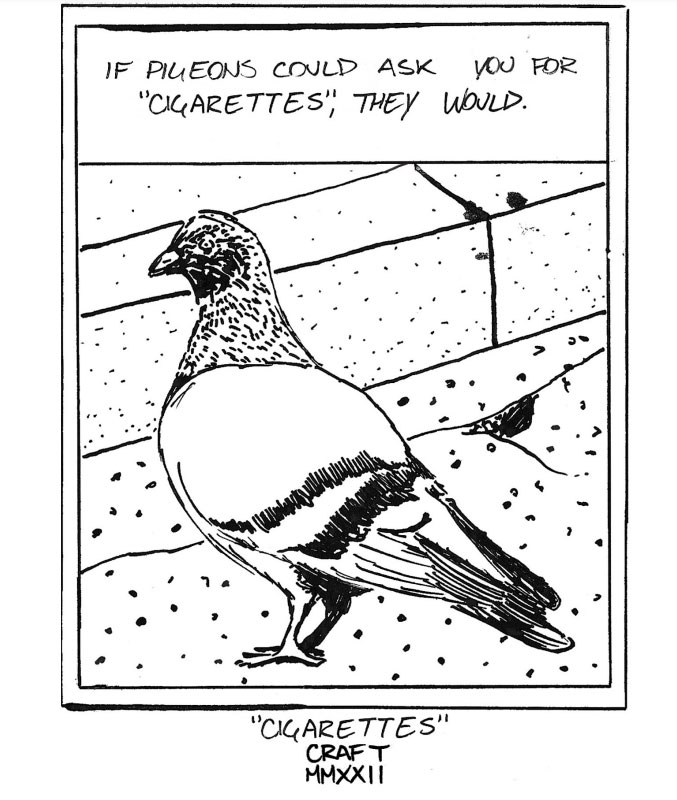

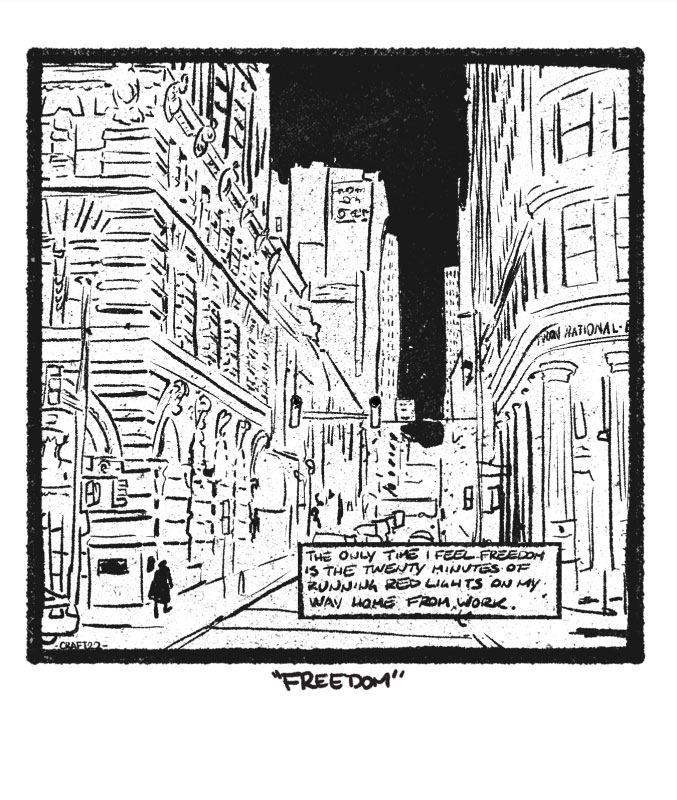

Text and Image

Angus Woodward

Alien Abduction

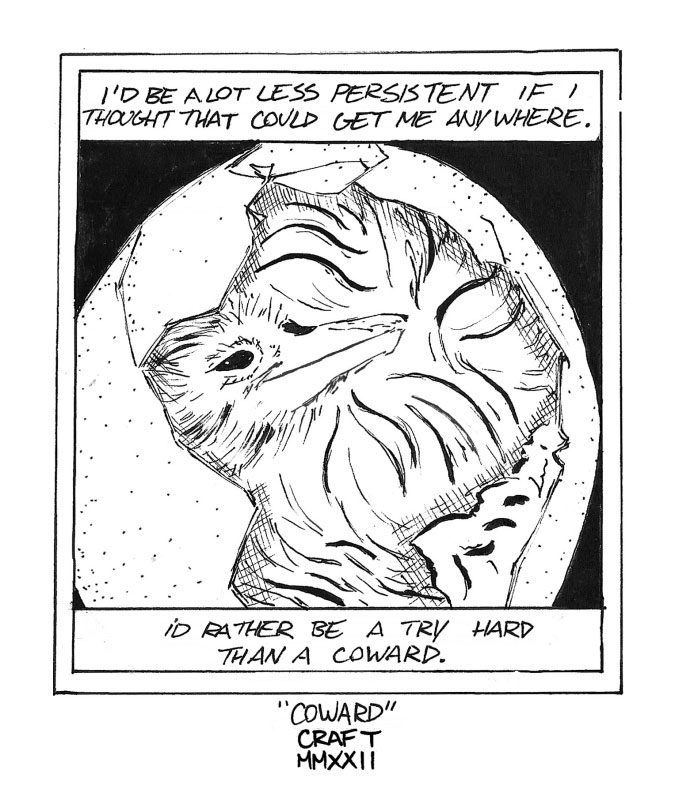

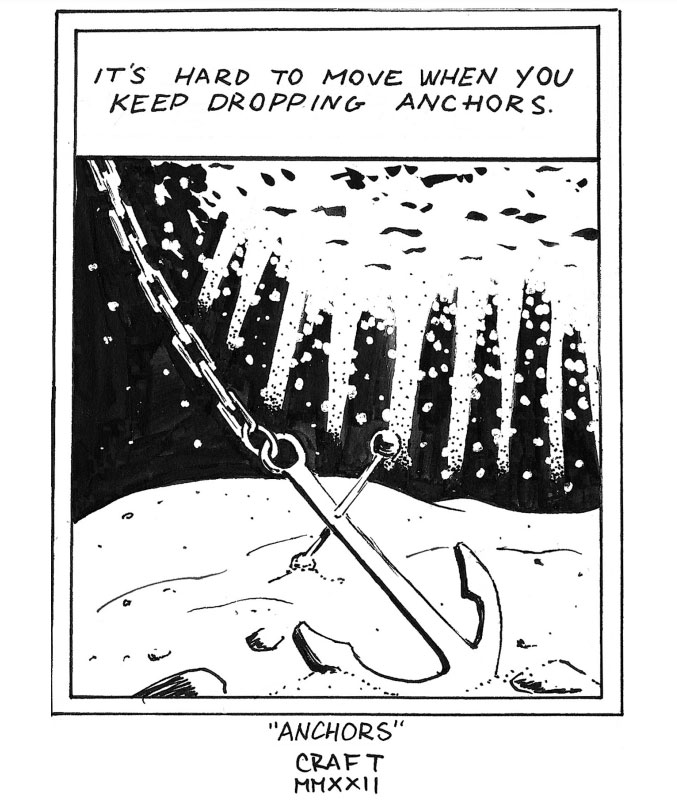

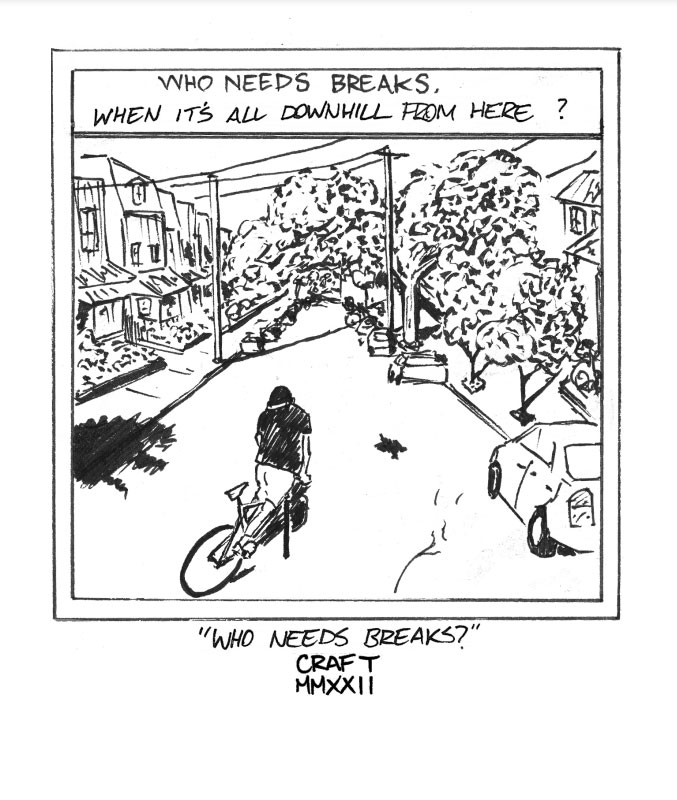

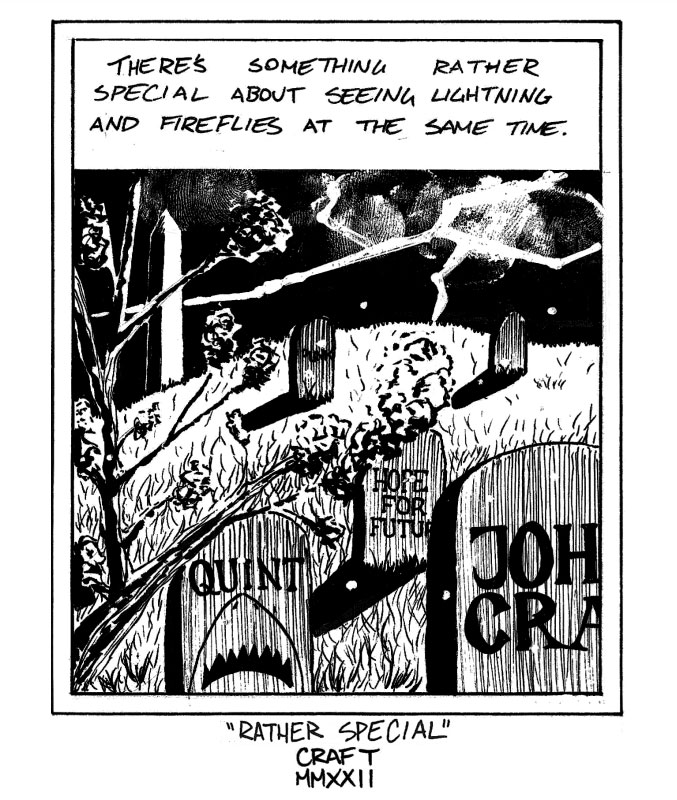

Joseph Craft

Reflections

POETRY

Sandra Newton

PERMANENCE

The bloom of the hydrangea may be more breathtaking

And lush in its multiple fullness,

The peaches more fragrant and heavy

As they drag the branch down toward the dark, moist earth;

The jays and doves that come with ruffled wings,

Only recently awakened from shells, with unsteady gait,

And the butterflies who need multiple attempts

Before they can sip enough nectar

And flutter off with footprints of pollen:

Beautiful and exciting notes

To tell nature’s story,

But transient,

Caught by a scanning eye,

Or only remembered from a past day.

Real nature is in the unseen germinating seed,

In the fruit’s ovarian pit that harbors life,

In the fragile eggs coddled and warmed in tree-blind nests,

And in the sticky-webbed cocoons where

Ugly, prickly-haired caterpillars dream of beauty.

We are allowed only a moment’s glance

Before all goes underground

To a restless sleep,

Waiting for the dawn.

J. Tarwood

When Rain Falls

(After Udiel)

To deny water is to deny your soul.

I shelter from time under

the balcony. Sleep’s

for memory. October

always has the melancholy

of anesthetized hours, humid

caresses without haste. To deny water is to deny our instincts,

fleeing words rooted in dirt. cursing

rather than blessing mud. To deny water is to deny your soul,

annihilating the shielding shadow. Years have freed me

from the phony quiescence of Spring.

Surrendering my solitude

as a sentinel, I give

myself to the rain falling on my face.

Emma DePanise

Northern Flicker

When I think of woodpeckers, I think of you

because what persistence, what sound.

Because I thought a neighbor nailing

and found instead this feathered frame

drumming a gutter and you are always

that surprise, sky-flecked and maroon. Because I will spend my whole

life forest-wide reverberating shapeless, foraging

through carving empty spaces. Because each rhythm

and hollowed-out home is yours. I give them

to you. Because we both know how to hold

the smallest excavations.

Megan McCormick

Sayable Things

There is a word for a dune

as if it is a single thing,

which is to say that what we call things

is often make believe

for what we want them to be. Ask any of the grains that have fallen

one on another, whether this year

or the last, and they will tell you that

one day the wind moved

and the grain moved with it,

and this is where it stopped

and the wind carried on. Which is to say that a dune

is a lot of things falling

together in their nows

without palms shaping them into a word

they need meet. Ask the snow that sits upon it now,

are you part of the dune

or are you part of the ocean? There is a word for a body,

as if when you trail your fingers

along your skin, the aches you hold inside

aren’t their own living things,

stories that replay each night

like they’re a carousel. As if when you stand,

the weight of a thousands words unsaid

doesn’t pool at the ankles,

bubble into heat tossed

at smaller, more sayable things.

There is a word for anger, too.

Robin Reagler

Perhaps

Hurricane Harvey, 2017

As the power gave out, the generator kicked in

As rain fell, I felt her ghost escaping through a window

Vanishing into green dusk

As the pet dog found its inner watch dog

I dragged both mutts across the mushy field of weeds

Helicopters buzzing above, filming us

And the rain fell and continued falling

In an endless loop of rainfall

And I honestly wondered if perhaps it wouldn’t end If perhaps I should open my mouth

Wide to catch it as it came down and down At night I never slept

There was nothing to be done

When we made love it was more about fear

And placing a barrier between ourselves

And the future which had become THE FUTURE

As I catalogued the details of the real

As real as the hand that glides into her

As real as the mouth that takes her on these shores

And with waves crashing down upon us I told her

A story

A story about simple times

A story erasing the story I believed was true

Because believing came down to this

And only this:

We are wind swept

Robin Reagler

The Thread

I used to be somebody’s daughter.

When sadness threatens to take me down, the rituals

kick in. I begin

by walking it out.

Sadness, the thread,

I, the spool. I walk to breathe

I breathe to think

I think to write

I write to love Sunshine hits metal

The brightness, blinding I want you to understand how I feel

[We pause inside this poem together]

Paula C. Brancato

The Dark

A lion sits on the golden stones of a building in Caltigirone.

A fiery Mediterranean sun sets.

I hold my daughter’s hand or did then. Why do people die?

The long days of Covid – I want to know.

In the piazza, water flows from the gargoyle’s head with the bitterness of iron.

The violinist sits in moonlight, in a white shirt,

his music

braille, as the fountain bubbles

like a player piano.

A tendu, she places the tips of her fingers into the palms of her lover,

rises en pointe,

pirouettes in darkness.

Mark Brazaitis

Ice

The first thing she’s going to do, she told me,

well, the first thing after the necessary things

like checking in with her parole officer,

like applying for a driver’s license,

like seeing if the clothes in her bedroom closet still fit,

which they might because, in the past month,

nervous about leaving (though it’s all

she’s wanted to do since she arrived),

she hasn’t eaten much more

than her fingernails, yes, the first thing she’s going to do

is find her figure skates. Her mother won’t have thrown them away.

Her mother has saved everything-broken Barbies,

elementary-school report cards, ancient drawings

painted colorfully, cheerfully, between the lines-

because she couldn’t save her daughter. She knows what world she’ll meet outside.

On job applications, she’ll check a box.

No bank will give her a loan.

Every man she dates will wonder, and some will ask,

Did you do it?-the crime-and, Did you…

you know…do it with one of…?

She’ll be out of prison

and forever a prisoner. There’s a pond behind her mother’s house,

If February is as cold as it was a decade ago,

it will be frozen.

She’ll skate like she’s a satellite

streaking around the sun.

She’ll jump like she’s a rocket to Mars.

If the ice is weak, the water she’ll crash into

couldn’t be any colder, or more terrifying,

than her first night in her cell

when she woke to a darkness

that would only have been merciful

if it had been complete.

Marte Carlock

Painting The Window Sill

I was painting the window sill

a mosquito lit in the wet paint

there was no saving her even if I wanted to

she had no way of knowing how or why

that place once safe had changed I guess the cosmos works like that

where sometimes for reasons unexplained

rash decisions yield happy consequences

and routine ones are fatal.

Robin Reagler

The Dead Stalk Us

Someone is following you tonight, but fret

Not. It’s just my mom on the haunt.

She left all her sneakiness behind

When she died. If you listen

Closely, her footsteps chime, there’s data

In every echo. Walk as though

You are asleep, whisper love songs

To yourself, and you’ll be fine.

Neighbors are taking turns trailing you

Both, making sure you’re safe.

Overhead there’s an astronaut orbiting

Planet Earth. Let that be me,

Magnetized to you both, as I truly am.

Now you glide Into the open

Field, hands deep in the pockets of your

Dress. You want so much

To turn around, offer her an arm to steady

Her in her trek, but that can’t

Be. So instead you look for the bird

Nest that is her obituary, the willow

Tree that is her legacy, and into the sky. Please

Know that I am up here, half

To blame for my own phantom madness,

Drowsy with passion I never knew was

Mine, keeping my desire a secret, even

From myself. From the sky,

The blurring shapes sharpen.

My dead mom winds her way

Through these nights. Shelter her

Until she’s ready to move on.

FICTION

Douglas Steward

Electronic Alchemy

It was tantalizing to behold, the boulder-sized glob of yellow- ish-orange stone, illuminated by the dappled sunlight in my driveway. My sixteen-year-old, Luke, helped Dr. Jurcik carry it inside to my home office. My bliss ended abruptly when Luke hastily deposited the monstrosity on my credenza, resulting in a loud “clunk.” “Try not to scratch the furniture,” I said. “It’s all I have to bequeath you when I die.” He shrugged. “Dad said I could have the leather couch in his apart- ment. That sounds like a better investment.” “Thirty-five pounds of gold,” Dr. Emil Jurcik said. “That comes out to a value of approximately one million dol- lars. Think of how many desks you could buy with that amount of money.” Luke’s eyebrows shot up. “Mom, that’s more than the money you lost on those stock options.” “Let’s not broach that subject right now,” I said. “What you see here used to be electronic waste,” Dr. Jurcik said. “Computer parts, old VCRs, cell phones. That sort of thing.” “And now it’s gold?” Luke said. “How’d you manage that?” “That’s what I’m here to talk with your mother about, young man.” “Whatever you do, don’t leave her alone with it,” Luke said. “Goodbye, Luke.” I shooed him out into the hallway, then turned my attention to my new client, Dr. Jurcik. When I began my practice as an intellectual property attorney, I chose to work remotely from home. It gave me time to pursue other interests and set my own time schedule. And all I had to do was put up advertise- ments on the Internet and the inventors came calling. That’s how Dr. Jurcik found me. He was willing to drive all the way from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, to do it. I was en- amored by the way he rolled his r’s at the end of a word, such as vaterrrr instead of water. It was disarming. “This will shift the paradigm of environmentalism, our economic fu- ture, and stun the scientific community around the world,” he’d told me over the phone. I hear that sort of thing a lot. Inventors are great boasters. Dr. Jurcik turned out to fit the bill as a prototypical Hollywood stereo- type of an Eastern European professor. Small in stature, salt-and-pepper mustache. Apt to lose his glasses on top of his head. I offered him a cup of coffee at my kitchen table. “I didn’t think they gave out degrees in alchemy anymore, at least not since the Middle Ages,” I said. “A very narrow field, I’ll admit,” Dr. Jurcik said. He took a sip and asked for a spoonful of sugar. “You need a diverse background to become credentialed,” he said. “I have advanced degrees in chemistry and metallurgy. And I’ve also made an extensive study of the Late Medieval period in Europe.” “You’ve studied history?” “Most of the important scholarly work in alchemy takes place then. That is, until King Henry IV of England made it a felony in the year 1404. Most alchemists don’t believe this is binding anymore. Especially in the United States.” “You have anything to substantiate your claims? I’ll need to see a mar- ketable process before we can proceed.” He rooted around in a well-worn briefcase, then pulled out some dog- eared papers. “You can indeed turn lead into gold these days. All you need is a particle accelerator, an endless supply of energy, and a terrific amount of lead. You end up with such a minuscule amount of gold that it’s not economically viable.” “But you have something better?” “Ah, yes. Electronic waste, we have an unlimited supply of it. Twenty million tons is disposed of worldwide every day. Only a tiny percentage gets recycled. The rest of it sits in landfills, poisoning our groundwater by leaking substances such as mercury, cadmium, and lead.” “Electronic waste?” “E-waste for short. I’m talking about computer motherboards, key- boards, DVD players. LCD televisions that no one wants anymore. That’s the real magic here. We need a lot of it to produce a single ounce of gold, but fortunately we have a lot to work with.” “Sounds like you could become very wealthy doing this.” Dr. Jurcik secured his eyeglasses on his nose. He looked me straight in the eyes. “Beyond your wildest dreams,” he said. “That’s why the alche- mists of old were so enthusiastic about it.” I made copies of his notes, gave him some standard legal forms to sign. He climbed back into his Subaru wagon and departed. I made a quick scan of his research papers. The whole thing seemed preposterous. He didn’t segregate the materials. According to his notes, he just dumped the whole mess into an apparatus he had developed and flipped the switch. Still, I was enamored. Luke caught me examining the golden nugget in my office, tapping on the side of it and listening for an echo. “Are you considering biting it to see if it’s real?” “I would if I could get my mouth around it.” The chunk of gold captured my imagination. I ignored the stack of pa- perwork that spilled over in my inbox. It could keep until later in the day. Instead I found myself returning to the Internet forums, reading inflated opinions on how this particular stock is over-margined or another has garnered way too much short interest. There were opportunities galore out there if only I had the capital to purchase some options contracts. If I can find some way to leverage this immense dome of precious metal, I could get back on track, I thought. The giant dollop of gold sitting on my desk rightfully belonged to Dr. Jurcik. He did say he might pledge it as perhaps a down payment on legal fees. That meant I had a claim on the gold, at least in the broadest view of the law. The rest of my Saturday was ruined as far as accomplishing anything constructive. Try as I might, I couldn’t concentrate on work. I kept turn- ing around in my chair and checking on the massive blob on my creden- za. Maybe it was just the lighting or my fertile imagination, but I could swear that thing moved. I told Luke to get his things together after dinner, I would drive him over to his father’s apartment building. Neil and I separated two years ago, just when Luke was developing into a teenager. That time was fraught for all of us. If Luke was affected by the shuttling back and forth between our marital home and Neil’s apartment every week, he didn’t show it. I would have liked more time with him but Neil forbade it. Something about me being a less than positive influence on our son. Neil described our marriage as one big chemical reaction, a process that converts two or more substances into something completely new. He’s a biologist so he says irritating things like that. I argued with him that the original elements are still there, lurking just below the surface. I was flummoxed when he agreed with me and suggested a trial sep- aration. Just like Neil to use my own words against me. I made myself my normal Monday morning cup of coffee, mahogany black right out of the French press, with a hint of sugar tossed in. Still in my slippers, I traipsed into the office, prepared to tackle some legal briefs. Maybe take a break by 9 a.m. to peruse the financial forums. I’d forgotten about the large mound of reconstituted e-waste on my credenza. The sight of it caused me to let go of my coffee mug. The black, inky coffee spilled along the cracks and divots in the wood floor all the way to the area rug under my desk. The giant rock of precious metal had lost its golden hue and darkened to a rainy-day gray. Worse, it had begun to warp and deteriorate. Its once oval shape now resembled a mountain- side where half had been blown off by a geothermal explosion. It was melting, right there on top of my credenza. I could see the outline of a computer keyboard sticking out of the top of the brackish mound. It peeked out, gray and misshapen, looking for a way to escape. I summoned all my courage and touched the crested butte of gray. It felt rough and plasticky, like the square bin where I kept my old LP collection. I regretted not checking on it that Sunday. But Sunday was my day to do absolutely nothing, to recline on my sofa in a T-shirt and running shorts and catch up on episodes of Billions. Neil usually took Luke to church. Good for him. I frantically tried Dr. Jurcik on my cell. An automated voice told me that his voicemail was full. He probably never bothered to retrieve his messages. As intimidating as that molten gray dune of lava was, I decid- ed to push on with my work that morning and then catch up with Dr. Jurcik later the next day. I mopped the coffee off the floor. I even ate a tuna sandwich in front of the gray menace while I perused some intraday trading charts. “Who am I kidding, looking at this stuff?” I confessed to the sinister mound of circuitry behind me. “This is how I went broke in the first place!” It glared back at me. I decided to ask Luke to carry it out to the garage on Wednesday, when he was scheduled to return from his father’s apartment. By Tuesday morning a large portion of the gray blob had dripped off the credenza and onto the floor. What looked like a melting motherboard pooled on the floor, capaci- tors and PCI slots erupting up from the sludge. A river of wires and plas- tic parts meandered past solid-steel desk legs, oozing into the crevices between the wood planks. The dull-gray mass of coagulation threw off an acrid, pungent odor. I was afraid it might burrow right through the floor into the basement, not stopping until it had tunneled straight to China. I spent the day rescuing my files and relocating them to Luke’s bed- room upstairs. Then Luke surprised me by showing up that afternoon after school. “I thought you weren’t returning until tomorrow.” “Can’t I stop by for a snack and to see my favorite mother?” “You’re here to see the gold.” “Of course I am,” he said, grabbing two Oreos from the kitchen cab- inet. “I have to warn you, things have changed.” “You found a way to spend it already?” he said, finishing off the cook- ies in one smooth motion. He opened the door to my office and stood there, mouth agape, black cookie crumbles clinging to his teeth. “What’s this? And what happened to my golden college fund?” “I don’t know. It’s somehow reverted back to its essential elements.” “No, this is something new. And hideous.” “That’s why you’ll be staying at your father’s until I get this situation resolved.” I couldn’t risk his prolonged exposure to it. For all I knew it was emit- ting carcinogenic vapors. He tapped the gray motherboard on the floor with his shoe. “It’s like we’re living inside that movie about the killer globule, The Thing.” “You’re referring to The Blob with Steve McQueen, and please step away before it eats your tennis shoe.” I rustled around in my basement, looking for an old hazmat suit left over from a previous client. I stepped into the white, plastic bodysuit and pulled the neoprene hood over my head. I adjusted the anti-fog visor on my face and approached the gray effluent with trepidation. It was diffi- cult handling a shovel in my oversized rubber gloves, but I managed to get ahold of it alright. With great effort I inserted the blade of the shovel under what I took to be a dot matrix printer emanating from the ooze. With all my might, I heaved. Not an inch of it budged. To make matters worse, the shovel was caught fast. It stuck straight out into the room, a sideways flagpole. I quit in a rage, stomping out of the room and removing the hood to catch my breath. Later I watched that shovel slowly become enveloped by the gray sludge. I felt like tossing the hazmat suit in after it. By the next day the gray monster had bloomed into a muddy mass two feet high that took over half my office. A fax machine emerged from beneath the gray quagmire, right in front of my built-in wooden shelves. Who uses fax machines anymore? I worked a safe distance away on my spare laptop at the kitchen table. I was determined to reach Dr. Jurcik. Only he could reverse this eco- logical disaster that was happening in my office. I phoned Washington University and asked for Dr. Jurcik’s extension. “Can you spell that, please?” “Emil Jurcik, he’s a professor there.” “We have no record of a Jurcik. We have a Dr. Jurkiewicz.” “Fine, what does he teach?” “Germanic studies.” “Why not just connect me to the Alchemy Department, please? I’ll speak with whoever picks up the phone there.” “I don’t know if the wizard is available right now.” I could hear snickering in the background. I hung up, humiliated. I remembered that the Mackrells, neighbors of ours on an adjacent street, became fed up with the consistent flooding of their pre-war-era basement after every major rain. In due time insects infiltrated their house, mobilizing in their custom kitchen and sending Sheila Mackrell into a tizzy. They hired a pest control company to nuke the bugs and put the house up for sale. I needed Neil’s permission before I could sell our home. And I didn’t want to alert him to the ecological terror that had seeped into an asset we were both still responsible for. Especially because I’d squandered most of our assets before, namely Luke’s college fund. My goal was to sell the house, split the proceeds, finalize our divorce, and move on from this misadventure. “Where will you live?” he said. I moved my phone to the other ear. “I haven’t thought it through that far.” “Of course you haven’t.” “Neil, are you going to make this a thing?” “It’s only because this is how we ended up in this situation in the first place.” “Neil, it’s been two years since we separated. The house is the only thing holding us together.” “At least we still have that.” There was a long silence before he said, “Luke told me there’s some- thing wrong with the house, that’s why he’s been living with me all this week.” “Luke has a vivid imagination. Remember when he wanted to develop his own cryptocurrency?” “That was your idea.” “Yes, but he believed me. Very impressionable, that one.” Neil finally gave in. He always does. I counted on him to do that. I glanced at my office door. The gray mass was flowing past the desk chair that I’d forgotten to liberate. Too late now. My next call was to Fay Bunting. Fay’s a Realtor from this well-connected family in Grosse Pointe; ev- eryone knows at least one of the Buntings. Fay would know someone who would covet buying a Grosse Pointe Park original, despite a few minor bumps and bruises. Not to mention a grayish toxic goo taking over the spare bedroom/office. “That’s quite a pungent bouquet,” she said when she arrived, pulling a handkerchief out of her purse and holding it to her mouth and nose. “Where is the offending organism?” I escorted her to the door of my office. She raised up on the toes of her high heels, examining the gray in- vader. “A little staging can do wonders, right?” I said. “Perhaps place a big winged-back chair in front of it?” “It’s fairly conspicuous, I’m not sure we can hide it.” “What about air fresheners? I could bake some cookies the morning of the first showing. I hear that can do wonders.” She removed herself from eyesight of the calamity and took refuge the kitchen. “There’s not enough chocolate chip cookies in the world that will mask that odor.” “Or,” I continued, “say it’s a piece of modern art. People go for that sort of thing nowadays.” “I suppose.” “What do you think we can list the house for? I owe two hundred thousand on it.” “That much, huh?” “I’m hoping I could split the proceeds with my husband. We’re sep- arated.” Fay thought for a minute. “You’d better forget about price and just concentrate on finding the right buyer. For whatever you can get.” Fay scheduled three showings the next day. I vacated my upstairs of- fice each time, leaving my client documents securely locked in the filing cabinet in Luke’s bedroom and removing any clutter from the kitchen. I returned to find most of my house intact, including the protruding blob that occupied my office. I checked a Realtor app on my phone for feedback. Large family liked the backyard but are looking for a larger home. Single woman would prefer an updated kitchen. And more closet space. Young couple is having trouble with financing and have stopped looking for a new home altogether. After that the showings trickled to a standstill. Fay Bunting stopped returning my calls. Not that I blamed her. By then the toxic mess had breached the doorway of my office and slithered into the hallway, threatening to intrude upon the kitchen at any moment. It had already devoured Luke’s pair of hiking boots. It was at that point I realized I hadn’t seen Luke in almost a week. I scheduled a breakfast with him at the Original Pancake House, the one over on Mack Avenue. Oh God, it’s come to this? I thought. I’m scheduling meetings with my own son. “How’s it going in physics?” I began after we sat down. “That class is nonessential,” he said, tipping the dispenser and engulf- ing his gold-rush-style flapjacks with syrup. “I dropped it.” “Does your father know about this?” “He doesn’t ask about school.” Luke held up the empty syrup dis- penser so the waitress could see he needed a refill. “He doesn’t ask about much of anything.” “Come hell or high water, you’re taking that course next year, buster.” “Speaking of high water, do we still have a house to go back to?” I sighed and let my fork rest on top of my banana pancakes. “I’m not sure.” I suddenly wasn’t very hungry. Luke had no trouble digging into his flapjacks. He spoke in between chewing. “You should sleep at Dad’s. There’s always the leather sofa in front of the TV.” “I’m not quite ready to admit defeat and move in with your father.” I pushed my plate away. “But I’m not sure how I’m going to be able to practice law like this.” “We could live off my stock portfolio,” he said. “Where are you going to get the money to invest?” “I was going to borrow it from your golden nugget nest egg. Until you found a way to lose that too.” He grimaced and shook his head. “What do you want from me, Luke? I’m doing the best I can.” “Try being the responsible adult around here?” He mopped up his remaining reservoir of syrup with toast. “Is that asking too much?” I was too tired to reprimand him for that comment. I dropped him off at school and returned home. The gray mudslide had flowed right through the kitchen and into the living room. This thing was pushing me farther and farther away from my family, from my home, from my law practice. I was forced to wash the dishes in the upstairs bathroom. Never mind doing laundry. That had become a thing of the past. I sat at the top of the stairs and watched the gray river roll past me. I thought I could see a flat-screen television, its grayed-out screen surfac- ing high over the morass and then plunging back beneath the surface. Soon it would gush right out my front door and into my neighbor’s rose garden. Then it would become the city’s problem. All I could do was wait for my life to fully unravel and then perhaps take some responsibility for the hole I’d dug myself. Until then, it was just me and the gray demon. It heaved and seeped through the house below me, content to slowly take over.

Ashley Anderson

Zipper Pulls

After I reached my wit’s end, I booked a consultation for a zipper supplement surgery. Being at home with my family for the winter holidays had been slightly less than torture. My dad retired three days before his sixty-sixth birthday and, since then, had made it known that “everything’s about me now. I don’t care what anyone else wants.” I felt something building in my chest, sitting there and ominously growing as each day passed by, and I knew for sure that it wasn’t my sense of holiday cheer. During the last few days I spent with my family, even the sound of my dad’s voice was enough to cause my heart rate to spike. For the first month I was back in my apartment almost 700 miles away, the attacks started creeping up on me like those cartoon cavemen with clubs. I would be going about my day, minding my own business, when one of them would sneak up behind me and club me with an anxiety attack. Racing heart, tight chest, gasps for air. Uncontrollable crying. Inability to focus until after the attack subsided. After the first attack, I thought that it was my body’s way of coping with the tension I had experienced while at home for the holidays. A releasing of the pressure valve, so to speak. But after the second and the third attacks reared their heads, I knew that this was not a release, but probably a sign of something bigger going on. I remembered seeing a commercial on TV weeks ago about a new treatment for anxiety called zipper supplement surgery. In the commer- cial, a woman stood in front of the bathroom mirror while a voice nar- rated the scene. “Do you struggle with your feelings? Do you feel like you need to just let it all out? Then you may be a candidate for zipper supplement surgery!” The woman slowly unzipped herself in a way that made me feel like a voyeur as I watched. As the zipper tab moved farther away from the base of her neck, I could see all of her emotions fall out of her chest and into the sink, words like “anxiety” and “stress” and “joy.” They filled the basin and tumbled effortlessly onto the floor, sliding to a resting point that the emotions themselves looked comfortable with. Some stopped under the edge of the vanity, while another leaned back against the woman’s toes. At first, I didn’t understand why something that had become so com- mon needed a commercial, but I guess zipper supplement surgery had become just like any other medication. The commercial continued to play as the woman, fully zipped up, stepped over her feelings as she left the bathroom with a smile on her face. “Ask your doctor about zippers!” Before seeing the commercial, I had tried almost all of it: deep breath- ing exercises, yoga, meditation, watching my diet, better sleep habits – every exercise and lifestyle change I could manage. Nothing worked. As time went on, I increasingly just wanted to stay in my apartment and curl up on my couch, making myself easy prey for the little anxiety cavemen with their attack clubs. I explained this to the doctor during my consultation for zipper sup- plement surgery. “I’m worried that this is going to take over my life,” I said, “and I don’t have time for this to control me. I know that sounds bad, but…” “No, it makes sense,” he said. His shiny bald head gleamed under the examining room lights. “The purpose of zipper supplement surgery is to provide a coping mechanism for those who are struggling.” He contin- ued typing notes into the examining room’s computer. I assumed he was working toward building some kind of patient file for me and, as I talked, he took notes to determine whether or not I was a viable candidate for the procedure. I wondered why he didn’t finish the sentence after the word strug- gling. Did he think I was trying to take the easy way out of learning how to deal with my feelings? The sadness, the hopelessness, the fear I sometimes felt about anything and everything with no apparent cause? I told myself to take deep breaths as I felt my chest tighten. Recently, when my chest tightened with the anxious feelings that snuck up on me, I could feel the acid from my stomach rising in my chest and up toward the back of my throat. That made everything tighter, as if there wasn’t enough room for my insides and my anxiety in the same body. “Based on your symptoms and what we’ve talked about, it appears that you’re suffering from multiple issues.” He began rattling them off – general anxiety disorder, depression, and another that I was sure I had resolved by now, but apparently hadn’t. “I’m going to go ahead and rec- ommend the zipper supplement surgery for you. Let’s go ahead and get that scheduled,” the doctor said as he clicked through various windows on the computer screen. He picked up a card from a stack in the drawer to his left, scribbled a date and time on the card, and handed it to me. “When you call to preregister for the surgery, they will give you more in- formation about what you need to do before checking in on your sched- uled date.” The doctor looked at me and must have sensed something in my facial expression. “Have you had surgery before?” I swallowed. “No.” The doctor looked at me as if he was reconsidering his recommen- dation. “Don’t worry,” he said. “It’s become a pretty standard surgery.” As I walked out of the examining room, I looked down at the date and time scribbled on the appointment card. I had two weeks to prepare myself for a surgery to permanently change my body so that maybe, just maybe, I could find a way to learn how to deal with the feelings that I just kept pushing further and further down into darkness. He didn’t ask if I had insurance or provide me with any recommendations as to how someone pays for a zipper supplement surgery. I guess he just assumed that I could afford it. In the two weeks between the consultation and the surgery, I tried convincing myself that this was just one big set of body piercings. After all, I was comfortable with people pushing needles through differ- ent parts of my body to adorn with jewelry, so in my logic, there shouldn’t be that much of a difference. Right? Maybe. To try and calm my fears, I went online to the clinic’s website to see if I could find more information as to just what they, the surgeons, were going to do to me. I had so many questions as to how this works. How this didn’t work. There had to be something that a person gave up in order to have a zipper installed in their chest. After digging deeper than probably necessary or safe, I found a video of a surgeon installing a chest zipper. In my head, I wasn’t sure why I needed to clarify where the zipper was to be placed because, in all hon- esty, I had only seen people with zippers inserted into their chests. If it wasn’t for the tell-tale zipper pull popping out of shirts, then it was the lump right at the base of the neck in the winter, when people tried to wrap the pull up in their scarves to prevent the metal from absorbing the cold air. I clicked on the “play” icon in the video screen and began to watch. First, they knock you out. With anesthesia, not violence – a com- forting thought, considering I likened my anxiety to aggressive cartoon cavemen. I fiddled with the volume on my laptop as the video continued. On my screen, an operating room opened up before me as a reassuring yet slightly clinical voice explained the procedure. “Once the anesthesia has gone into effect, surgeons then open the chest cavity and score the sternum tissue.” I watched as the camera zooms in on the sleeping body on the operating table. There was so much blood, enough blood to remember why I decided against going into any kind of medicine despite being told that I had the smarts and compassion to be successful. The surgeon had cut through the layers of this person’s body, different shades of flesh and pink and red, and then hands off the scalpel to another set of hands. The surgeon then took a tool I hadn’t seen before from a headless set of hands and my eyes wide. The surgeon inserted this thing into the opened chest on the table, pressed it against the sternum, and the video recording captured the sound of tree trunks cracking as they’re being felled, sturdy and strong trunks being broken fiber by fiber. The tool itself looks like a demonic eyelash curler, which only reinforced my opinion that the ones you can buy at the drug store were, indeed, medieval torture devices. To make it worse – the surgeon does this more than once. This poor person’s sternum is almost completely torn apart. The video continued. “Once the sternum is marked, the zipper is measured and adjusted to account for the patient’s anatomy.” I shudder at the narrator’s use of the word marked. I watched as the surgeon lift- ed the long, seemingly heavy zipper off a steel tray lined with the same bluish liner you see on TV hospital dramas. The surgeon placed the zip- per just where they wanted it to be. “Once the zipper is measured and placed,” the narrator said, “the surgeon stitches the zipper into place. As the patient heals, the skin will bind to the zipper and it becomes a part of the patient’s anatomy.” A lull in the action. Everyone prepared for the first stitch. The sur- geon took a thick, bent needle from the assistant and dips it into a vial of clear liquid that I assumed was to help the zipper bind to the patient’s body. Next, the surgeon positioned themselves to best reach the bottom of the zipper. As the surgeon pierces the skin, the patient’s body convulsed as if being shocked by a defibrillator. The patient’s back arched, shoulders tucking in toward the spine ever so slightly, and the upper body fell back to the table with a thud. What I just witnessed made my eyes widen. I started to sweat. I wondered what made a sedated body move like that. “The stitching process can take as long as six to ten hours, depending on the patient’s response to the stitching serum.” While the narrator spoke, the surgeon prepared for the next stitch. Before I could watch another convulsion, I slammed the lid to my laptop shut and whirled around in my desk chair. “What am I doing?” I asked myself out loud, hoping that something in my apartment – the gray walls, the couch, the bright teal rug in the middle of the living room – would have an answer for me. As my surgery date crept closer, I did what I needed to do to make sure my life was arranged before this procedure. I drank as much water as I could the day before, knowing that I couldn’t have anything to eat or drink after midnight, during the darkness between today and tomor- row. I had a friend who was willing to sit and wait while the zipper was installed drive me to the hospital. I didn’t want to be alone because, for some slightly rational reason, I was worried that I was going to die and not come out of this alive. Maybe those anxiety cavemen were going to leap out of my chest and bludgeon me to death. Or maybe they would go after the surgeon and his team, leaving me sedated on the operating table with the inner caves of my chest exposed for the world to see. The last things I remember before being wheeled off to surgery are spotty. The odd shade of blue-green-gray on the walls. How the colors around me felt dull, even before the anesthesia sent me off to dreamland. My friend saying that I shouldn’t worry about the anxiety cavemen blud- geoning me. (When did I tell her about those?) A nurse collecting my clothes in a clear plastic bag with a cotton drawstring. The anesthesiolo- gist telling me to breathe deeply as they placed the mask over my mouth and nose. Me trying to fight back against the mask, feeling the wild hysteria of someone trapped and unable to breathe. A nurse or an aid or someone wearing scrubs gently but firmly grabbed my wrists. “Ma’am, you’re going to be okay. Just breathe deeply,” they said in a soothing tone. I remember breathing too shallow, too fast, before the edges of my vision went dark. Sometimes I think of the conversation I once had with a friend —for simplicity’s sake, we’ll just call him Friend—one night after class when I lived in the last city where I had an address. Friend was a captain in an Army airborne unit, served four tours in Afghanistan and Iraq, and almost died while practicing a jump. If he hadn’t joined the Army out of his felt obligation to family tradition, Friend says that he probably would’ve joined the Franciscans. Friend, like me, was a writer who was in graduate school because he just wanted to teach. That evening in class, we discussed an essay he wrote about how he would sometimes wake up in the middle of the night and conduct security sweeps of his house. Friend and I had talked about how PTSD changes not just survivor’s minds, but the minds of those around them, too. “Sometimes I wonder why my PTSD does to my kids. Especially my daughter,” Friend said as we stood under the streetlight halfway between the English building and the parking garage. The part of campus that surrounded us was rather quaint, student living learning community and other university-owned houses that looked like little Swiss chalets. The mid-fall trees still held onto some of their leaves, but the ones who had given in to the wind and the rain lay plastered on the concrete sidewalk. The tab of Friend’s zipper pull gleamed in the light as it partially peaked out from under the collar of his shirt. The same thing happened as peo- ple walking past on the sidewalk caught the light from the streetlamps. It wasn’t yet cold enough for the zipper pulls to be hidden under scarves and coats yet. I thought about what Friend had said about his daughter. I thought back to my experiences as a kid and how, more than once as an adult, I looked up things my dad had done or still does on the internet, looking for some kind of explanation for his behavior. The hyper vigilance, the insistence on being tough and going so far as to refusing to let my sis- ters and I cry when we were hurt, the requirement that everything had to always be secured—car doors, windows, kitchen cabinets—but yet it was against the rules for my sisters and I to lock doors in the house. My dad always told us that, even as adults when we would come home for the holidays, that we weren’t old enough to have earned or deserve that level of privacy. I didn’t mean to cry—after all, Friend and I had this conversation before, just not as personal—but I felt my voice crack and the muscles around my eyes contract. The thinking to myself shifted to thinking out loud. There was too much in my head that, in reality, would take years of therapy and the zip- per supplement surgery to begin to cope with. “The worse part was when we were little and tried to wake him up for anything. My dad sleeps a lot, and when it would be dinner time or we’d have to ask him a question, we’d have to stand far enough away where he couldn’t reach us when he woke up. Heaven forbid you should touch him, because he would come out of a dead sleep with the intent of going for your throat,” I said. “Did he explain why he did that?” asked Friend out of curiosity. “All he would do is yell,” I said. “I figured it out when I was older, but when you’re a kid, it’s terrifying thinking that your dad would try to hurt you just because you woke him up for dinner. But as an adult, it’s harder to grapple with the other ways he’s done things that have hurt me mentally and emotionally, because I can’t always walk away from those things.” Friend gave me a side hug. “I needed to hear that,” he said. “I needed to hear that.” I don’t know how long the surgery actually took. I woke up in a ge- neric-looking hospital room with the same kind of familiar surroundings I saw before I was knocked out for surgery: the strange blue-green-gray paint color, the beige curtain separating the beds in the hospital room. My friend sat beside me, reading a book. “Hey sleepy gus, you’re awake!” she said, putting her book down on the bedside table next to the phone. The table itself looked awkwardly bare. I tried to move and sit myself up a little straighter, but my lower back and hips screamed in pain just as much as my chest did. “Agh!” I cried as my body flopped back on the bed. The surgeon told me during our con- sultation that moving would be quite painful for the first few days after the surgery as my muscles and joints learned how to move again with the addition of the zipper. I panted as if I had just tried to run a 5K. My lower back and hips felt like they had just spent hours in yoga class doing vinyasas that only involved corpse pose and bridge pose. “Yeah dude, you might want to take it easy. They had you in there for awhile,” she said. “How long?” “Like, a good twelve hours at least. They kept giving me progress reports, but dang, you seemed to be taking forever. It’s Saturday.” My surgery was scheduled for Friday. A whole day had passed with- out me knowing. I could see the sleeplessness etching itself into my friend’s face. “You didn’t have to stay after the surgery was over,” I said. “Are you kidding? I want to see what this thing looks like!” Not quite the response I expected, but my brain was still cloudy from anesthesia so, to be honest, I wasn’t sure what to expect. There was a pause. “Can I see it?” she asked. “What?” “The zipper!” “Oh!” I imagined myself shaking the cobwebs out of my brain. “I mean, I guess. I don’t know how to do this, though.” My friend gently fiddled with the hospital gown until enough of my chest was exposed that she could see the zipper, but not so much that I would flash anyone who walked into the room. I gasped, not having braced myself for what I would actually look like post-op. She whistled through her teeth. “Dayum! That has to hurt like a bitch.” Her tone sounded more like she was talking about someone’s new tattoo instead of a completely foreign-to-the-body device implanted in my chest. But really, was there that much of a difference? The newness of the zipper shone menacingly in the artificial light of my hospital room. It felt heavy, like a folded weighted blanket sitting on my chest as I felt my lungs and diaphragm adapt to breathing properly with the added pressure to inhale and exhale. Blood, my blood, had dried around the seams where zipper met flesh. In some ways, I wanted to know what it felt like to unzip the zipper, what sensations happened when all of your feelings just came tumbling out of your chest and into the world. In other ways, I wished my friend would cover me up again. The zipper’s metal made my skin feel extra cold. I felt my eyelids flutter with sleep as the doctor walked in. “Good to see that you’re awake,” he said in a rather upbeat tone. I tried to stay awake, but my body decided that it had enough activity for now. My friend picked up her book and waved. “I’m going to head out now. I’ll text you later to see how you’re doing.” I nodded, not thinking to ask where my clothes and phone were. The doctor looked up my charts on his little device he held in his hand. “You’ve had quite the ordeal the past day or so, miss,” he said. I thought he sounded a little patronizing and I didn’t like it. “That was kind of to be expected, don’t you think?” I tried to chuckle. Even that hurt. “We had you in there for almost fourteen hours installing the zipper,” the doctor said as he took my pulse and listened to my heart. “Each time we wanted to make a stitch, we had to time it with a lull in your convulsions. There must have been something in there that wanted out pretty badly.” The cause of my anxiety, possibly? I felt the sarcasm that dripped from my thoughts pool in the base of my skull. The convulsions ex- plained why my back and hips felt the way they did. The doctor finished checking my vital signs. “I’ll let you get some rest,” the doctor said. It wasn’t long before I felt myself falling asleep, letting any leftover drugs take over my system and work their way out. Months later, I found myself sitting in my desk chair with that famil- iar feeling of tightness and panic. I was still learning how to move again. The physical therapy twice a week helped some, but even the cute ther- apist with the bright blue eyes and the buzzed dark hair couldn’t bring my body back to what it used to be. “Some people just never regain full mobility after this surgery,” he said with a sad look on his face. “No one seems to understand why.” In other words, I may never fully heal. I kept trying, though, because sitting still just made the feelings feel that much worse. I had to retrain my muscles on how to bend and twist again. We spent some physical therapy appointments just bending and twisting, while others we would stretch and toss a medicine ball back and forth. The therapy room was always bright and sunny. The aides were always friendly. Getting up and moving became a bright spot, even if my body felt after the lightest half hour of stretching. Sitting in my desk chair, the pressure of my feelings against my zipper became more and more intense. I tried to control my breathing, just like I had been taught. Focus on something tangible. Deep breath in, deep breath out. Keep looking at the random nail a previous renter had left in the wall above my desk. My skin and muscles that held the zipper in place began to ache, the kind of ache you get in your belly after you kept eating Thanksgiving dinner long after your stomach told you that it was full. It looked so easy, unzipping the zipper and letting your emotions tumble out. The woman on the commercial could do it. The people in the videos I watched as part of my consultation could do it. Why couldn’t I do that? I knew that I couldn’t wait much longer to unzip the zipper without doing damage to my healing incisions. I got up and made my way to the bathroom. I glanced at myself in the mirror and already saw the tears running down my face. If someone asked, I couldn’t give them a reason as to why I was crying, let alone tell them why I was having yet another one of these attacks. I peeled my shirt off and exposed my zipper, its silver color contrasting with the violet purple walls of my bathroom. Slowly, carefully, I tugged at my zipper pull and unclenched the teeth, pair by pair. As I created space for my feelings to fall out for the first time, I winced. I didn’t know what this would feel like. I didn’t know what to expect when something actually fell out of my chest. What would those feelings look like? Where would they go? I kept unzipping, and tiny pebbles fell out of my chest, slowly at first, but gaining more momentum as I continued to unclench zipper teeth. The pebbles hit the floor and slid under the edge of the vanity, landed in the sink, bounced off the counter and into the toilet. Tiny pebbles like the ones my friends’ toddler-aged children picked up at the park and put in their pockets for safe keeping. Pebbles continued to fill the sink and cover the floor. A tiny pile of them sat in the toilet, waiting to be flushed down the drain My breathing was quick and shallow, panting almost, as I stood root- ed to my bathroom floor and stared into the mirror. My zipper was completely undone, top to bottom, and I could catch the faintest glimpse of my sternum and ribs in the open space of my chest. I couldn’t look at anything except myself in the mirror, making eye contact with only my reflection as I continued to cry. It was as if my emotions needed yet another escape route beside the one carved out specifically for them. What had I done? I wiped my mouth on the back of my hand even though nothing was there. I felt a tense kind of satisfaction, similar to what it feels like after throwing up and the muscles around the stomach have just started to relax. I stood in front of the mirror until my breathing returned to normal. As I zipped myself closed, I winced as the tugging of the zipper pull forced my skin to move in ways it wasn’t meant to move. The tears came back as exhaustion descended. I rinsed my face with some water and looked at the pebbles. I thought about leaving them where they had landed, possibly making a note to clean them up later. Going to bed sounded like the next logical step, but I stood there, feeling paralyzed, not knowing what to do now that I had put my body back together. Instead of getting ready for bed, I slowly sank to my bathroom floor and sat there, knees to chest in a way that I thought I would never sit again, and stared at the pebbles. What to do with them, what to do next, did not come to mind. All I could do was sit and stare at them.

John Fretts

Cellar