TABLE OF CONTENTS

Issue 16

BOGGS FICTION PRIZE

Winner:

Max Carp for “Bobblehead Buddha”

FICTION

River Pearl

Karl Miller

POETRY

Normalcy

Angelica Whitehorne

Reflection

Lance Nizami

1909

Michael Campagnoli

High Wire Suite

Lee Peterson

I Seen You

Susan Johnson

Release From Small Town America

Yvette A. Schnoeker-Shorb

Confession

A.E. Hines

overcome

Sheryl Guterl

Erode

Sheryl Guterl

In These Unbearable Times

Ronald J. Pelias

“We Shall Overcome”

Ronald J. Pelias

The taking of momentary permanence

Liza Wolff-Francis

Remembering Black

Linda Dimitroff

Long, Long Road

Brad Garber

Pledge

Brad Garber

life still moves in quarantine

Corbett Buchly

Drowning in Place

Jennifer Atkinson

The Thrill of Travel

E. Martin Pedersen

Road Song

Jessica Needle

Möbius Strip

James K. Zimmerman

Social Distance in the City

Michael Salcman

The Expiration of the CARES Act–Eviction Protection

Susan Manchin

Rage

Holly Karapetkova

My Soul is Always Mated

Craig Cotter

The Duet

Eva Maria Sher

For Walt, in April

Donna Pucciani

The Phone Call

Barbara Brooks

Paula

Paula Brancato

Everyday, You Say

Richard Levine

Trespassers Will

Richard Levine

We once

Jessica Cohn

End of Day

Jessica Cohn

Standing Still for Survival

Yuan Changming

Time Signature

Brittany Mosley

Rich Soil

Brittany Mosley

Lost Again in the Ghosted Wilds

John Powers

Leaf Blowers

Grey Held

State Flag

Nicholas Kasimatis

Enough of the Land is Burning

Nicholas Kasimatis

Lines Written in Old Age

Lisa Elaine Low

A History of Patriarchy, Faerie Style

Katharyn Howd Machan

A Soldier’s Dream

John Grey

Semper Paratus

George Searles

Teton County Resolution

Jeffery Alfier

Laying the Stone

Jane Ann Flint

Rising

Sarah Morgan

The Man Who Made Money

Reed Venrick

Coin

Rikki Santer

The Voice

Andy Oram

Toad

V.P. Loggins

Question

V.P. Loggins

Dumb Luck

Yvonne Higgins Leach

Impediments

Louise Kantro

It Must be Nice

Lourdes Dolores Follins

Logic of Negation

Adam Day

Us, and the Rain

Joel Peckham

Virtual Sermon, Easter 2020

Joel Peckham

Pandora

Joel Peckham

CREATIVE NONFICTION

Somewhere on the Other Side

Allison Dixon

Linear Meditation on “For Eleanor Boylan Talking With God” by Anne

Sexton

Beth Copeland

Emergency

Harvey Silverman

Rainbows & Widows: Brokedown in Dodge City

Tracy Haught

Expiration Dating

Morgan Florsheim

An Adventure Palette

James Carbaugh

Rosaries Like Lightning Bugs

David Chura

How Much Can the Heart Take

Kimberly Cardello

Delivering the News

Bob Chikos

Halfway Twice is Yet Not Once

David J. Frost

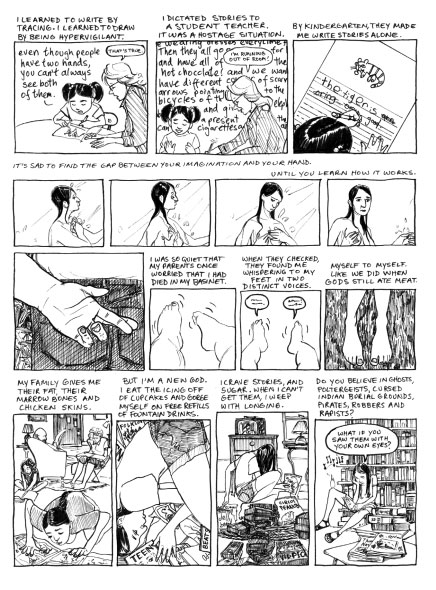

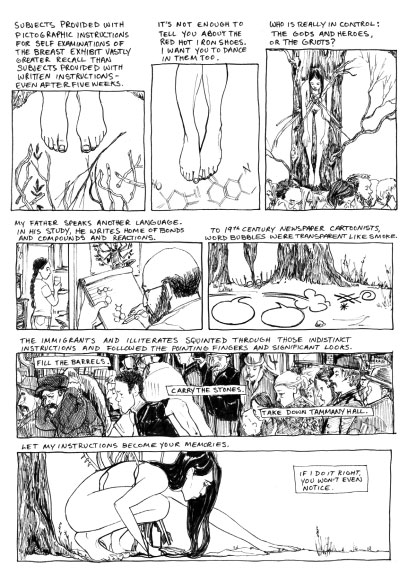

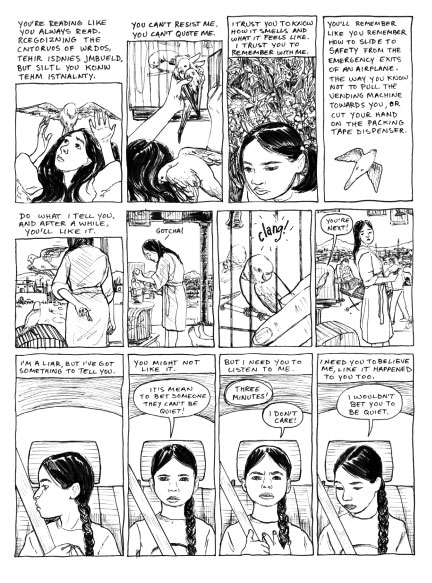

TEXT and IMAGE

See What I’m Saying

Rachel Masilamani

BOGGS FICTION PRIZE

“Now the time has come for you to seek a path.”

The Tibetan Book of the Dead

In the pitch-dark room there were signs of life. A deep sigh flushed out like the last words of a mute. The mattress squeaked, followed shortly by light footsteps and then complete silence, that grim augury before a major earthquake, which is what that moment felt like to him, a life-long Los Angeleno.

He parted the drapes and a flood of California sunlight nearly blinded him where he stood. He shielded his eyes in defense, annoyed by the intrusion in what would otherwise have been a rather complacent state of mind. He could read the signs when dialed in, as he was now, and he was quickly overcome by the portents of a nefarious presence floating in the air around him, an Asura monster poking at the outer edge of the visible world.

Perhaps another fateful day for Landon Briggs, in other words.

Well into his thirties, Landon fancied himself a man of the world. There was an “Om” tattoo on his neck, forming the centerpiece in a flower-of-life type of symbol. He got the seed of that tattoo not long before he left the roost and went to conquer the world. He was about sixteen at the time, lived for rock ‘n’ roll and thought, with the innocence of youth, that a sound-of-the-universe symbol on his neck would curry favor with the music gods. That wasn’t the craziest thought to ever cross his mind.

He’d constantly worked at embellishing the tattoo and, if not for Time, it’d probably end up covering his entire body like some kind of Buddhist version of the Illustrated Man.

“What did you tell him?” Landon asked the naked woman lying in bed. He turned to study her as she picked her clothes off the floor, the yellow light making her look like a Greek goddess in some bucolic Arcadian landscape. Melanie looked even better now, he thought, than when they’d first met ten years previous. The blink of an eye in the grand scheme of things, yet a span of Time containing most of his adult life. Major events nestled in like rosary beads, one for their brief courtship, one for the wedding, one for the pregnancy, one for the birth of their son, one for the divorce, and now another bead for her engagement to a man he loathed. And so on.

“The truth,” Melanie said, “had to go to a funeral.”

“I’m sure my old man appreciates that, wherever he is,” Landon said. “Thanks for coming.”

“Someone had to,” she said.

Funerals always filled Landon with a sense of embarrassment he couldn’t quite place, and his father’s funeral was no different. It was almost as if he felt shame for the deceased, like they’d suddenly lost their day jobs and were soon found roaming down Skid Row at night, glugging a slug of Skol out of a brown bag. A change of status that he didn’t want to be associated with, as he’d always learned to keep it positive, if only to alleviate the feeling of being constantly cursed. But it wasn’t that, of course. It was just fear. Overwhelming fear.

“Y’know, I been thinking,” Landon said, immediately putting Melanie en garde with that last word, thinking. “Don’t marry that guy. I wanna come back home. A boy should grow up with his dad, don’t you think.”

“Nevermind Tyler, don’t bring him into this,” she said.

“His birthday’s coming up, when, Tuesday.”

“Wednesday.”

“Wednesday. Let’s spend it together, the three of us, way we used to.”

“You get him something?”

“’Course,” Landon said, “it’s a surprise.”

Melanie rolled her eyes, accustomed as she was with his equivocating ways. She moved her hair out of the way as she fastened her bra.

“Okay, nevermind Tyler,” he said, “this guy you’re gonna marry, you ever had any doubts about him?”

She pointed to the bed like a police detective would the scene of the crime. “What do you think this was all about?” She came up behind him real close, not hugging or anything, just stood there and Landon again felt that warmth between them, like a tangible physical presence with a consciousness of its own, although he couldn’t tell if it was birthing itself on the spot or if it was something recalled from happier times.

“Do me a favor, don’t tell Tyler about my old man,” Landon said. “He never even met him, y’know, don’t feel like answering a thousand questions about the afterlife.”

As they shuffled into the sparsely furnished living room of this two-bedroom walk-up apartment in Sherman Oaks, Melanie reached for an envelope resting on the IKEA coffee table and handed it to Landon. He still received the occasional mail at this, his old address, and he picked it up on his weekly visits to his son. Landon took a quick glance at the envelope. Probably some junk mail from the Army, he guessed, as he ripped the envelope open only to quickly realize that the letter was anything but junk. It had the official “Department of the Army, Headquarters California Army National Guard” header, addressed Memorandum to Landon Scott Briggs, so there was no mistake about it. Landon’s eyes quickly slipped down the page as his worst nightmare was confirmed.

He’d heard rumors of ex-soldiers having been asked by the Army to pay back their re-enlistment bonus but thought it was some kind of mistake, that something like that could never happen in this day and age. And yet, there it was, a letter to the effect that he had to pay back his $21,000 bonus, the very reason he went back to that Middle Eastern hellhole in the first place. The letter said that the payment was made in violation of DoD guidance, and in violation of federal law, as if it was Landon’s fault that he was offered the money. The sheer injustice of the bait and switch ruse left Landon frozen. His mind went racing to images of carnage and mayhem, all within state limits.

Tyler’s room was a shrine to horses. Pictures, posters, netsukes, even a used old saddle, a B-movie prop Landon found at the flea market on Melrose. He’d asked the seller for a certificate of authenticity but none was forthcoming and with his son crying his heart out for everyone to see what a neglected little squirt he was, Landon reluctantly shelled out the money. A few days later he caught that western on late-night cable and suffered through two hours of gay cowpokes spewing stilted lines but, to him, spotting his saddle was like looking for a stolen bike in Tiananmen Square.

Tyler had his ear buds on, watching pixelated horses jump over pixelated hurdles in a looping simulation game that struck Landon as uncannily life-like in its repetitive tedium. The child looked preppy, with his reading glasses, a button-down shirt, khakis and a V-neck vest, a look Landon didn’t approve of but had to concede it matched Tyler’s temperament and general disposition. Landon removed Tyler’s ear buds, startling him out of his alternate reality, “C’mon, bud, they’re about to open the gates.”

He shuffled Tyler out the door, lagging behind just enough for an aside with Melanie. “Hey, Mel, can you do me a favor? I didn’t get a chance to swing by the bank this morning.”

“Sixty okay?” she asked, springing for her wallet, as per usual.

“You mind?” Landon said, grabbing the cash like yet another lifeline, already thinking of cutting into his new debt by the end of the day.

* * *

The Santa Anita horse racetrack always held a special place in Landon’s heart. It was the scene of some of his most glorious moments, stories he’d kept repeating ad nauseam, constantly embellishing them until even he started questioning their veracity. Alas, it was also the place that had seen the worst of Landon, days he’d rather forget. The days he lost money, and there were plenty of those, didn’t bother Landon in the least, as he had no attachment to accumulating wealth or even something much simpler, like a nest egg. No, what really messed with his head was that empty feeling the morning after a big win, the moment he realized that, had he set his mind to it, he could have every little thing in the world and yet could never have it all. He saw himself as a mythical lion taking a bite out of Earth, wanting to relish every flavor, every feeling, every thought, all there was to know in this realm of experience.

He wanted to swallow the Moon and spit out the Sun.

Landon showed Tyler how to fill out a betting form but the kid found it hard going, like he was running on diesel fuel or something. The child nodded like a good soldier and Landon slammed sixty bucks on the counter to announce his presence in the Great Hall. Soon as he got his tickets he had Tyler kiss them for good luck and that finally got the boy going.

Landon loved his son to death and he lived for moments like this. In layman’s terms he wanted to shower his son with the love and attention that his own father never bestowed on him, and in so doing, Landon would gain the respect of at least one human being and also prove to himself that he was at least good at something. Something like hitting a trifecta, so to speak. While not overly attentive to the particulars– he once got Tyler the wrong and, dammit, non-refundable, prescription glasses– he did remember each and every experience they shared. Landon liked to recall a story he once heard from an itinerant Buddhist monk, or whatever his correct nomenclature was, down at the Venice Beach boardwalk. The monk showed him a crystal-like bead that he carried in a small velvety pouch and said, with an authority beyond Landon’s ability to fully comprehend, that it was one of the most prized relics to be found on earth. “It is called a śarīra,” the monk said. “The śarīra are to be found in the cremated remains of the great Buddhist spiritual masters,” he said, holding the sacred object in the sunlight for emphasis. “They cannot be found in the ashes of ordinary folks like you because, you see, the śarīra are made up of elements not of this earth.” After much cajoling, the monk let him touch the śarīra but to Landon’s disappointment it felt no different than rubbing a glass bead. Just the same, the story stayed with Landon and he came to think of his entire life boiling down to the times spent with Tyler, his only śarīra able to survive the cauldron of his tumultuous existence.

Tyler got a mark on his forehead from pressing too hard against the rail, sticking his little arm out to touch the galloping thoroughbreds, like so many purple unicorns, as they warmed up before the race. “They go by too fast, daddy,” Tyler said, nearly dropping his ice cream cone.

Landon took Tyler on a spontaneous tour of the quarters, filling in the dead time with stories about the rules of the game, and how they name horses and how the meaning of those names oftentimes decides a horse’s fate before even running a single race. Much like with people, he thought, but kept that to himself. He then walked Tyler into a stable for the big reveal and watched the boy’s face drop as he realized that there was nothing impromptu about their tour. Landon introduced the boy to his old buddy, Big Ben, a jockey he’d met in AA a lifetime ago, and his racehorse “The Lion’s Den”.

“How you feelin’, Big Ben?” Landon asked.

“Feelin’ pretty good. If I were you I’d bet everything on this guy,” Big Ben said.

“Not crazy about the name, The Lion’s Den,” Landon said. “Like my life’s in danger or something.”

“Kinda name makes you think.”

Ben checked Tyler out, the two looking like classmates height-wise, ages apart in worldliness. “Don’t be shy,” Big Ben said, and grabbed Tyler’s hand and ran it over the side of the horse and then over his wet nostrils. “He likes it when you do that.” For Tyler it felt like a communion of sorts, completely natural yet far removed from his daily experience. “Can I get up on him?” Tyler asked, a glitter of childlike excitement in his eyes. Big Ben got one of Tyler’s feet up on the stirrup, and the boy helped himself onto the saddle for a view of the top of the world.

“Why don’t you get your boy a pony, Landon?” Big Ben said. “I know someone has a Chincoteague pony for sale. Cute and friendly, considering.”

“Considering what?” Landon asked.

“They’re born in the wild, on an island.”

“How do they end up here?”

“Pony penning.”

“What’s that?”

“Local firemen herd’em across the shallow waters at slack tide. Take’em from one island to another, then auction off the foals. Rain or shine, they go swimming across that channel, into the unknown.”

“Oh, man, I bet you that scares the hell outta’em.”

“They ain’t exactly going to the slaughterhouse, y’know.”

“Yeah, but they don’t know that.”

“God knows what goes on in their little pony heads, but it’s a sight to see.”

Landon felt a pang of sadness over the fate of the Chincoteague ponies, and was about to make an offer, or rather the promise of an offer, when he heard a familiar voice booming over his right shoulder.

“My horse just got over a case of the colic, now you turned it into the main attraction at a petting zoo?” the intruder bellowed.

Big Ben brought Tyler back down to earth, literally, and turned his full attention to his employer. “Mr. Rocanna, sorry, sir, I just–”

“Outta the way,” Mr. Rocanna said. A middle-aged man dressed in a crisp white suit, knee-high leather boots, straw Panama hat, he hopped on the horse like he owned it, which he did. The wall behind was painted pale blue, and the man appeared like a war hero from a middle-aged painting, rallying his troops against the backdrop of an innocent azure sky.

Landon was suddenly overwhelmed by a feeling of déjà vu at the sight of Mr. Rocanna. He’d seen him around the course and up in the club, had spoken to him on several occasions, the conversations always taking strange turns into the abstract, but didn’t recall ever seeing him in the barn. And yet, the feeling was unmistakable, and Landon felt a rush of nausea take over him.

Mr. Rocanna leaned forward, as if to listen to the horse. While deep in metaphysical quicksands, Landon heard Mr. Rocanna’s words before they were even uttered. The sounds came at him from all sides, front, back, above, and below, all at the same time, disorienting Landon into paralysis.

“You people got him spooked,” Mr. Rocanna said. “Make sure you loosen him up before the race.”

“Yessir,” Big Ben said, all business.

Landon looked away from the blue aura enveloping Mr. Rocanna and glanced in the direction of the white light coming in through the barn and leading up to the track. He quickly regained his balance, just in time to notice the confusion on Tyler’s face, a sense of disappointment difficult to hide. “The gentleman owns this beautiful horse,” he said to his son in the way of explaining the balance of power. “I got your horse singled, Mr. Rocanna. Put all our money on it,” Landon said, like it was some kind of accomplishment. “Didn’t we, Tyler?”

Mr. Rocanna whispered something in the horse’s ear and the horse turned its head, one big eye fixed on Landon. Mr. Rocanna sat back up straight on the saddle, his eyes glowering down on Landon, who must have felt like he was looking up at the marble statue of a vengeful god, or an avatar to say the least. That spooked Landon and Tyler both.

“Oh, they’re still here?” Mr. Rocanna said to Big Ben, meaning Landon and Tyler. The child looked down, embarrassed. He tried to gently nudge his dad out of an increasingly uncomfortable situation.

“Wait now, sir, we didn’t come here to–” Landon said, just as a bell sounded in the distance.

“Did you hear that bell? Means it’s time for you to go gamble away your rent money,” Mr. Rocanna said.

“Okay, I see what you’re doing,” Landon said, spotting another ruined moment in the rearview mirror. Big Ben grimaced at Landon, in the way of an apology.

“A nice lesson to teach your child. I see the likes of you here all the time, and I know all about you in particular,” Mr. Rocanna continued. “Don’t act so surprised.”

“We have to leave now, Tyler,” Landon said, but his body didn’t follow his mind’s command.

“What is your name, young boy?”

“Tyler Gordon Briggs.”

“Well, Tyler Gordon Briggs, the reason I’m sitting up here is because I have a nose for winners, a flair that extends, many would agree, to people. And in your father I’ve seen, in our past conversations, that special sparkle in his eyes. You know the kind I’m talking about? The spirit struggling in human form. The spark of life, the pneuma of deus absconditus for us grown-ups. Look at this horse here, a beautiful animal, but study its face closer and what do you see? Dead eyes. Look at Big Ben now, a winning jockey and honorable drunk, but take a closer look. Dead eyes.” Big Ben nodded in agreement, resigned to his fate, as Mr. Rocanna carried on. “But your father, Tyler, is a different breed. He’s at heart a street philosopher, the best kind of philosopher, and yet he’s wasting his life away at the tracks. I think he ought to know better lest you, young stud, wish to continue his legacy. Like father like son. And is there any reason in the world why you might want for that, my dear Tyler Gordon Briggs?” Mr. Rocanna said.

The child shook his head, near to tears, and looked down. “I wanna go home now, dad,” he said, gently tugging at his sleeve. Landon kissed his son the way he’d done in the past when he would hurt himself during a game of catch, or fall off his bike and get a bruise, but this time it was different. Landon looked at his son and realized that the walls surrounding his innocence had just caved in and the child standing in front of him was no longer the child he’d brought to the track that morning. That child had died to childhood.

At the same time, Landon couldn’t help but notice that something inside himself turned too. He’d heard the type of cautionary words spewing from the mouth of Mr. Rocanna before, as he’d been the subject of many such well-meaning yet ineffective interventions. The weight of Mr. Rocanna’s words, mere platitudes in another context, registered not in the words themselves but in the whole experience, which Landon suffered through to the innermost particle of his being. It was that rare time where the lines between the physical, the moral, and the spiritual got completely blurred. Matter of fact, Landon had to think back to reassure himself the whole thing wasn’t just the effect of some late-kicking pill someone might have popped into his mouth the night before, which incidentally was also a blur.

* * *

“Had fun at the park, Tyler?” Melanie asked, but all she heard was the sound of the door closing behind the boy.

“I think he’s coming down with a cold or something. Been cranky all day,” Landon said. “I don’t know what’s gotten into him.”

“Can you watch him the rest of the evening?”

“Naw, I gotta go see Frankie about something. Why?”

“I got a shipment of cigarettes coming in.”

“When?”

“Four o’clock.”

“See what I mean, this Ray guy’s a fuckin’ prick. Makes you work on a holiday. Don’t know what you’re doing with him.”

“He promised us health insurance.”

Landon rolls his head back in a dramatic gesture, like someone just laid a trump card on the table, leaving him to count his losses. “Well, can’t beat that.” She’s heard enough already, and she opens the front door for Landon to take a hint.

“You see the price of cigarettes lately?” Landon said, thinking out loud. “That load must be worth a million bucks, huh.”

“That’s why I have to be there myself, make sure it doesn’t end up in the wrong hands.”

“That liquor truck got boosted last year, word on the street is Ray did it himself. Sold the goods to a Chinese fence and later collected on the insurance, doubled up on it. Way to pay for your fancy wedding.”

“Forgive me if I don’t believe the word on the street.”

“He’s just another crook, Mel. No better’n me.”

“Prove it.”

“Oh, you mean if I were to show up here tomorrow with a million bucks you’d send Ray packing and give me a second chance.”

“I’m open to miracles. It’s always been my policy,” she said. “Go, now. Your friends must think you’re dead.”

It was a long drive downtown, hitting the I-5 southbound at peak hour, which only made Mr. Rocanna’s putdown earlier in the day come back into Landon’s head like a killing fields buzzard. Fuck, Tyler’s gonna remember this incident for the rest of his life, he’s old enough to retain these kinds of memories. Matter of fact, to that day Landon still held a vivid recollection of a particularly savage beating he received, courtesy of his own dad, when he was about Tyler’s age. He’d asked his old man to let him move in with his mom, and Mr. Briggs’ resentment towards his ex-wife came to a boiling point. The belt was Mr. Briggs’ (he demanded that his son called him Mr. Briggs) weapon of choice and the metal buckle left two thick scars, like an X, on Landon’s back. “X marks the spot,” his dad used to joke whenever Landon asked about his mother’s whereabouts. A couple years later, he overheard Mr. Briggs talk about her in hushed tones with some of his buddies during a Fourth of July barbecue at the house. It turned out she’d died of some disease or other; Landon never asked, disappointed as he was with her for abandoning him at the crossroads. In the intervening years, her image slowly faded in Landon’s mind, and with nary a photograph to jog his memory, she became as immaterial as a notion, an idea of something that consumed him for not understanding it, yet another hungry ghost in his life.

* * *

A few months prior to Mr. Briggs’ passing, Landon got a call from Cedars Sinai to come pick up his dad, as he was unfit to drive himself home after a round of radiation therapy. It took Landon a few moments to string up the chain of events that led up to that call. He hadn’t seen or spoken to his dad in years and was actually surprised to hear that he was still alive. Mr. Briggs was dying, it turned out, of lung cancer by way of a two-pack a day smoking habit that he’d maintained religiously throughout his adult life. And he listed Landon as the emergency contact on the hospital form knowing full well that Landon would take pity on him in the hope of settling some old scores.

Landon recognized his dad’s old red plaid shirt first before acknowledging the wraith inhabiting the space within. They didn’t speak while Landon loaded him up like a piece of fragile luggage into his car and quickly got onto Beverly heading East towards the 101 Freeway. The quiet unsettled Landon and he kept bobbing his head up and down to a silent tune in his head. It was a nervous tic left over from the days he’d go around wearing massive headphones at all times, blasting heavy metal straight into his astral body.

Mr. Briggs pulled out a cigarette and lit it up with trembling hands. “Hope you don’t mind,” he said, breaking the silence. Landon kept shaking his head as the old man took a deep puff. Landon snatched the pack of cigarettes out of his dad’s hand and tossed it in the back seat.

“Won’t make no goddamn difference any–,” Mr. Briggs said, and promptly burst into a coughing fit. When he settled down a bit he reached into his pocket and took out a couple of small trinkets.

“Went back to Vietnam last year,” he said. “Got this thing here for your son, he’s how old now, seven? Boy loves his horses, don’t he… Saw that on the social media and whatnot.”

“What’s this?” Landon asked.

“It’s a Tibetan windhorse,” Mr. Briggs said.

“What’s a wind horse?”

“They say it’s like the soul. They call it Lungta.”

“Say again?”

“Lung-dah, that’s all I know. You asking me what his name is in… American? I don’t know, call him what you want. Tell your son it’s from his granddad, who got it from a Tibetan monk in Vietnam. That’s the story. Tell him that.”

Mr. Briggs then took the second trinket, a bobblehead Buddha, and placed it on Landon’s dashboard, a wicked glint in his eyes. “For you, free spirit,” he said. “Ain’t that the damnest thing, huh? Same monk sold it to me, for a pack of Marlboros,” and started laughing, then coughing, then laughing again. “No reason to hate that place… Vietnam… no reason at all.” Landon’s head bobbed up and down in sync with the bobblehead for a moment before checking himself, feeling stupid all of a sudden for being cut down to the size of a toy.

Landon dropped his dad off at his rent control apartment on Alameda, close to Chinatown, about where East meets West within the city walls. “I didn’t know any better I’d tell you to stay outta trouble,” Mr. Briggs said. He thanked him for the ride and told him he’d call if he needed him, but never did, and with that Landon was summarily dismissed.

Next time Landon saw his dad was at the funeral, where he couldn’t help feeling regret over throwing the horse trinket in the nearest trashcan along with the dashboard bobblehead Buddha and Mr. Briggs’ unused pack of cigarettes. Thing is, he wanted no link to the long line of cursed and short-lived Briggs males but that act of defiance now registered as sacrilegious, save for the pack of cigarettes, which ended up pretty much where it belonged. Landon kicked himself for acting on impulse, as he would’ve liked Tyler to have something to remember his grandpa by. If nothing else, a worthless toy and a cool little story to go with it can go a long way towards explaining a man to a child. Aside from that, Landon could’ve really used a dashboard Buddha. He envied the genius that invented that trinket.

* * *

While in the throes of recalling that particular episode, an idea suddenly popped into Landon’s noggin like a revelation from the ethereal realms and the more he thought about it the more real it became, all the little details falling into place like markers on the road. He saw the path wide and clear in front of him and all he had to do was take it and never look back. He turned the air-conditioning to full blast, trying to cool his brain from over-drive down to a more manageable pace. He could think of only a few other times in his life when he’d experienced that type of tunnel vision, where he could clearly see his future, albeit short-term, laid out in front of him with such mathematical precision. The light at the end of the tunnel was his son. Well, Melanie, too, but the two came as a package deal, he reasoned, and who could blame him. But Landon tried hard not to get ahead of himself for once. After all, he had a heist to plan out and execute that afternoon.

Landon took a seat in the bleachers at the old Derby Dolls roller rink. About a dozen girls skated around the banked track at great speed, oozing aggression. Landon cringed at the sight of the pivot catching a high elbow and ending up on her lily ass.

“You keep flappin those wings you gonna fly right the fuck outta here,” the coach barked out as he rushed to the railing. Frankie DiDio carefully cultivated his boot camp instructor persona, the buzz cut, the fatigues, the phony appearance of having things firmly under control. It did give him street cred, on sight, and leverage with a certain class of ladies, gluttons for punishment, even when his own conditioning was lacking and his weight ballooned for no apparent reason as he was pushing forty. He and Landon were army buddies, and that was a bond that cut through all the mundane bullshit, of which there was plenty to go around. They almost came to blows on several occasions, over either pussy or money or simply as victims of self-created Hobbesian traps, but they always ended up burying the hatchet deep in some WeHo dive bar.

The pivot picked herself up off the floor and rolled back on the track, blonde locks jutting out from under the helmet. Stephanie waved slightly in Landon’s direction before switching effortlessly into a killer on wheels. The name on back of her jersey read “Barbie Drone”.

“I’m gonna get that fuckin bitch,” she proclaimed.

“Yeah, please help yourself,” Frankie said. He turned to take his seat back in the first row next to an open bottle of beer and spotted Landon a couple rows back. “Where the fuck you been, man? Thought you was dead.”

Landon’s head bobbed up and down. “Oh, you know me, just trying to keep body and soul together.” He jumped over another row, got closer to Frankie, and showed him the recoupment letter. “Did you get one of these?”

“Yeah, got mine couple of days ago,” Frankie said. “I say we start a war. Right here.”

“Can you drive a truck?” Landon asked.

“Yeah, I can drive a truck.”

“I don’t mean like a U-Haul or a pickup truck. I mean like one of’em big rigs, eighteen wheeler fuckers.”

“I can drive it forwards, backwards, parallel park it, hotwire it, hell, I can do donuts with the sumabitch. So, yeah, I can drive a truck.”

“Where’d you pick that up?”

“Kuwait City.”

“Oh, before my time.”

“Naw, you was there. Holed up in the brig, staying true to your name. It was when we beat up on that ensign, if I recall, scored one for the below-the-deckers.”

“Shoulda been you in the brig, I barely scratched the guy,” Landon said.

“We had a shipment of Strykers, had to line-haul’em into Basra and they were short on drivers, so they trained some of us. Rode the Highway of Death all the way to Hell and back.”

Landon took a swig out of Frankie’s bottle. “I was drinking that,” Frankie protested, before re-directing his anger at the players. “Gimme four laps, fast as you can.”

“You can’t drink,” Landon said. “You’ll be driving a truck in a couple hours. I got a solid tip and I thought–”

“You talkin’ about stealing,” Frankie said with the excitement of a child getting the correct answer in grammar school.

“Well, yeah.”

“Why would you steal a fuckin’ truck?”

“It’s what’s inside the truck, dummy. Cigarettes,” Landon said, letting that sink in. “We got no choice, Frankie. It’s written in the fuckin’ stars.”

“Who else is in on it?”

“Just you, me, and a pretty girl.” That’d be Stephanie, fresh off the track, casually sliding onto Landon’s lap right on cue. She was pretty, in a Suicide Girls kind of way, especially with her derby doll gear on, helmet dangling on her hand like a severed head. With no apparent invitation, Stephanie stood up and lifted her skirt, exposing her right buttock to Landon. “Look, I got a fresh bruise right here.” She then grabbed Landon’s hand and dragged him away like a hooker in the lobby of a house of ill repute. She put her helmet back on because, well, she meant business, that’s why.

Judging by the way the next episode unfolded, or didn’t unfold, depending on perspective, if Stephanie were the paying party she’d be entitled to a refund. She did let out some moans, facing the wall of a dark hallway leading to the locker rooms, but they signaled exasperation more than anything, seeing as Landon was fresh out of vital fluids, having just tapped out for his ex inside the hour. He pulled his pants up and stepped away graciously, the least he could do. “Sorry, my mind is elsewhere,” he said, his ego in the basement, “but I can eat you out.”

Stephanie took her helmet off and tossed it, hitting him squarely in the chest. “I hate hating, but I’m hating on you right now,” she said.

Theirs had been a volatile relationship from the beginning. They met at a Halloween Party in Hermosa Beach the year before and instantly connected when they played the old parlor game “Who’s your favorite Buddha?” At the count of three they both blurted out “Buddha Amitabha!” and then shared a long, warm hug where no words were spoken, or necessary. Buddha Amitabha’s nineteenth vow was to appear before those who called upon him on the moment of death and offer them protection and safe passage to his Paradise of Ultimate Bliss. The idea appealed greatly and equally to Stephanie’s New Age hipster friends and Landon’s North Long Beach ghetto brothers alike, as it promised safe spiritual refuge after a life lived at one’s contentment, a philosophy of life akin to riding a roller-coaster into the Big Nightclub. All they had to do was remember the password to this ultimate VIP lounge. Easier said than done, as Landon found out during his first tour in Iraq when a bullet pierced his right shoulder and all he could think of was, first, was he still alive? Check. No limbs missing? Check. Cock and balls? Triple check. Repeat. Then for the next hour, as he was being medevaced to Camp Arifjan out in Kuwait, his thoughts revolved around how soon he could leave the theater of war and return home to catch his son’s first day of pre-K. Not for a moment throughout this whole ordeal did he think even once of Buddha Amitabha. It was only on his flight back home while gazing out the window at an ephemeral formation of noctilucent clouds that the thought crossed his mind and he reproached himself in silence, and promised to do better next time, as he understood that he had just been tested.

* * *

The railroad track fed into the depot terminal and a crane whirred and screeched as it lifted a trailer off the train car. Landon and Frankie observed the action via binoculars from the comfort of Stephanie’s Mustang Shelby convertible, limited edition. They spotted Melanie as she walked around the terminal holding a clipboard. A young, burly truck driver signed the delivery papers for her. The door to the depot office opened and Landon cringed at the sight. Ray Barbas, a middle-aged man dressed sharply in a crisp suit, walked up to his fiancé, Melanie, and the two had a brief chat. Just before they went their separate ways Ray grabbed a handful of Melanie’s ass. She feigned disapproval.

“Ouch! That’s your ex, huh,” Frankie said, needing no binoculars to spot the infringement. “Now I get your disappearing act.”

“Fuck you guys talking about?” Stephanie asked, stifling a yawn.

The Mack tractor backed up and rammed under the marked trailer. It wedged the kingpin locked, and the coupled unit rocked back and forth to secure the lock.

“Damn, this is gettin’ me horny. That weird?” Stephanie said.

* * *

The speedometer on the Mustang hovered at around forty-five, Stephanie’s goldilocks blowing in the wind like flocks out of Medusa’s head. A car honked as it passed her, but she didn’t turn, she just smiled like she’d spotted a sign that said the plan was going to work. Her eyes were glued to the Mack truck in the slow lane in front of her. She caught up with the truck and drove alongside it, hooning like crazy, just maybe a nose ahead, enough for the truck driver to take notice of her. She casually looked up, as if by accident, and caught the trucker’s eye. She waved, and he grinned like an idiot. All she had to do now was reel him in.

She accelerated ever so slightly and the truck stayed with her. She turned and flashed that beautiful Cali smile again. The trucker tipped the brim of his greasy hat, feeling like he had a real chance there.

Landon, driving a beat-up Corolla a few car lengths behind, Frankie riding shotgun, kept a close tab on the action.

Stephanie looked up at the trucker, waited until there was eye contact, then pointed to the back of his truck. The trucker shook his head, confused. Stephanie flailed her arms, signaling that something was wrong with the truck, possibly a flat tire, hard for anyone to understand what she meant.

The trucker adjusted his rearview mirror, rolled down the window, but couldn’t quite make out the damage. Stephanie honked a few times to make her point before speeding off into the sunset like a good Samaritan.

Landon slowed down and edged into the lane behind the cargo truck. “C’mon, man, pull over.” Landon was familiar with this area of Long Beach, what he called Baghdad by the Bay, and he knew that once the truck hit the freeway it wouldn’t stop until it reached destination.

Landon kept his distance until, finally, the truck signaled for a turn. The cargo truck pulled up on the shoulder, close to an overpass, hazard lights blinking. The trucker stepped out and proceeded with a quick inspection. He bopped the tires with a mallet, checking for flats. As the trucker circled around the back, Landon pulled up his car roadside of the truck and Frankie rushed out of the passenger seat and into the truck’s cabin fast as a jailbreak.

This is when Landon noticed a strange figure standing tall in the middle of the overpass, looking down on the action. The lanky, swarthy man wore a long, dark overcoat and top hat, a strange getup for that neck of the woods and that time of day. Odder yet, he was carrying a suitcase. Not a briefcase, mind you, but a suitcase. But what unsettled Landon most was the fact that this mysterious Traveler was not trying to record or photograph the thieves in flagrante delicto, he wasn’t there to witness, he was there in judgment. Landon had no doubt about it and, as omens go, that was as bad as they come.

To Frankie’s delight, the keys were still in the ignition, as expected, and he peeked out the window and gave Landon the thumbs up. He pushed into the clutch, whacked a red button on the dash and the truck took off with a whoosh. In the oblong side mirror he spotted the truckless driver jumping up and down for some reason.

Landon looked up one more time before clearing the scene but the Traveler had already vanished. He spotted a rainbow in the horizon, although it hadn’t rained in months, the holy fires were raging from Siskiyou County to Shasta to Sylmar, and the bone-dry earth was crying for thunder. He wanted to call Frankie for confirmation of what he’d just witnessed but the rattle and hum of emerging traffic soon closed in on him like an iron maiden and the moment was gone forever.

Landon ditched his car in a CVS Pharmacy parking lot a couple exits North on the 710 and hopped into the truck with Frankie. They took on a labyrinthine route, not so much for evasive purposes as for buying time to hatch a plan to sell the booty, and they both put on their sunglasses in unison as they hit the 10-West, once it was decided that Chinatown was their only option.

“This is the Chinaman who hacked a dude in half right in front of his restaurant,” Frankie said. “In broad daylight.”

“Rumor has it,” Landon said.

“Over nothing, guy owed him a jade turtle or some shit. And you trust him.”

“I’ve dealt with him before. Guy’s fair as a fairy. He’s got like an army of vending machines all over town. He’s gonna sell these for top dollar.”

“I don’t even know what I’m gonna do with all that dough. You think about it?”

“I got debt collectors breathing down my neck. I wanna settle.”

“That’s just plain stupid, man,” Frankie opined. “Not to mention un-American.”

“Every now and then you gotta balance the books, or someone’s gonna do it for you.”

All the while Landon had a grin on his face. He’d just thought of the best birthday present for his son. He imagined the whole day in detail, how he’d buy the Chincoteague pony in the morning, have it transported to Melanie’s place, though not inside her apartment, that’d be dumb, but rather tie up the pony to a parking meter across the street, then drag Tyler downstairs on false pretense and reveal the big surprise. Landon got carried away as he pictured his little boy’s joy, and the sweetness of that simulated moment felt almost real, even though deep down he knew he wouldn’t live to see it.

“You realize, we just done start a war,” Frankie said, “Fuckin’ love it.”

“How do you see this ending?”

“Can’t worry about that… like you said, it’s already written in the stars, innit?”

The truck changed lanes to overtake a slow moving bus. It swished gently and Landon noticed for the first time a moving object in the middle of the dashboard. It kept shaking its head, a dashboard bobblehead Buddha, much like the one Mr. Briggs had given him, swaying with the turns in the road. And not just any Buddha, it dawned on Landon, but Buddha Amitabha.

“Frankie–”

“Yeah.”

“You ever think of dying?”

“Nope. You?”

“It’s a funny thing, you know. Much as I try I just can’t picture myself dead. Why do you think that is?” Landon asked and glanced over at his buddy to demand an answer. None was forthcoming.

An earthquake expert on the AM radio station was ringing the alarm bells for the imminent Big One, being not a matter of if but when. Landon turned the radio off and eased his mind into the hum of the West-bound traffic, which presently came to a halt and, as he looked at the road ahead to see a mile-long snake of cars heading mercilessly into the mouth of the sinking Sun, his attention rested on the bobblehead Buddha nodding in a rhythm that would appear, at first glance, chaotic and random, but which belonged in fact to a higher order, one that effortlessly set the score straight between the past and the future, and for one brief moment Landon felt at peace with the world.

He spent the rest of the ride in funereal silence.

THE END

Remarkably, DreamWorks’ “Antz” and Pixar’s “A Bug’s Life” were released within six weeks of each other. Both films have worker ants as heroes, saving their colony and falling for a princess in the process.

Ants swarmed over our porch ceiling like discordant musical notes released from their scales. They raced down the wooden pillars and over the cracked concrete floor. Out of nowhere and suddenly. One ant played the fife, another limped, and another played drums. Somewhere, a queen had given the signal.

Or maybe that was in a movie about ants I saw with my kids when they were young. Two ant movies—Antz and A Bug’s Life, animated by rival studios—came out at the same time, confusing everyone. Which fast food joint was giving away toys from which movie? They seemed to have the same plot: a misfit ant who finds God. We saw them both, but I wasn’t paying much attention back then, half-asleep in a dark theater of screaming children. I would fail the Bug’s Life vs. Antz showdown trivia quiz. My kids, Sid and Anna, might do better, but it’s not something we compare notes on in our random and infrequent phone calls. Antz. That z jazzed up such a pedestrian word. I started uzing z’s instead of s’s because I myself needed to be jazzed up. The marriage was dragging, or I was dragging it down, slumped into a nostalgic torpor for all my bad habits abandoned. In a way, I’d cleaned up my life. In another way, everything I’d sucked up sat inside me like a vacuum cleaner bag overflowing with dust, but I had no new bag to replace it with.

The kids are both mostly grown and living time zones away from Pittsburgh, where we take comfort in the lack of clarity—hills, clouds, limited vision. They’re off with their mother, sending back beautiful pictures of their beautiful lives that will not fade, unlike the cheap color photos we took when they were children. The color faded to an indistinct pinkish hue in the old albums—the ones with the dried-up stickum that failed to hold the photos in place any longer. When, in my nostalgic moments for the tiny ants that only showed up for crumbs and sweet stuff, I pull out one of the albums shelved next to the dusty cookbooks, all the photos slide loose out of the pages like those ants boogie woogieing down the pillars—like “Surf ’s up, Dude!” The neat lies of those ordered albums tumbles into a realistic mess on the floor.

*

The real ants—big black carpenter ants—are here, quietly invading in their bumbling yet direct script across the gutters, soffit, fascia, down the pillars, and over the cracked cement I’m standing on.

I’ve always enjoyed killing ants. Even outdoors, which can fairly be considered their turf. I used to sit on my parents’ porch on hot summer days smushing ants with a popsicle stick after I’d finished slurping down the colored, frozen sugar water. A couple of sweet red drops melt to the cement, then word gets out, then Squish. Squish. Like the grim pleasure of pouring hydrogen peroxide on infected cuts to watch it foam up, or popping pimples as a teenager, despite all warnings against it. One of my kids, Sid, was/is? a cutter, which horrified me and my second wife Del, the kids’ mother. We did a purge of every sharp thing in the house, though missed a tiny yellow pencil sharpener the size of a large grape. And we missed the great outdoors, and every sharp thing that cut him out there. And every sharp word in our failed marriage.

Last I heard, my first wife Clare’d gone to Bazookia as a missionary for a year. Too busy keeping track of Del and the kids and negotiating through the losses. We all agreed on one thing: the divorce was my fault. Del used to tell me that if I had an affair, she’d cut my balls off. At least she didn’t do that. The kids were at the opposite of perfect ages for something like that: 12 and 13. They knew exactly what I did. I think I had my own death wish about marriage. That was the squeaky hinge on my life—the end of ten years of marriage.

Okay, listen, Anna and Sid. I’m just trying to explain why I lost track of Clare. I’m not blaming your mother.

*

Why did I take such pleasure then? Why do I take such pleasure now? Maybe because it’s a small cruelty you can get away with—the lack of blood, the miniscule and brief evidence of their existence. The easy justification—the little ants eat our food, and the big ones eat our houses. The traps. The poison.

The poison that kills them, the poison we feed on. There’s a whole series of horror movies about giant ants due to guys like me. Ants getting revenge. We are ants, too, though. Somebody’s ants. And if you believe in God, we are God’s ants and God holds the popsicle stick, and sometimes it drips down some sweetness and we briefly imagine a place called heaven.

I’ve never been a fan of heaven, and even today, when we’re burying Clare, I can’t imagine her there. She’d be miserable. I’ve always hated when people say what the dead would have liked or not liked, but Clare, in heaven? Traditional heaven? With no vices to lean on, she’d lose her balance and fall all the way through purgatory and down to hell, where I can see her smiling, conspiring to drive Satan crazy.

Clare had a death wish, but it was like a carnival ride that goes amok. Enjoyable at first, adrenaline pumping, wow, this is fun, I feel so alive, then it goes off the tracks into space and you’re asking, Is it supposed to do this? Like the cartoons where the coyote runs off the cliff into air and doesn’t fall until he looks down.

The moral of that story is supposed to be “don’t look down,” but I believe you have to look down. Which is why I’ve never been a fan of heaven. What’s heaven if you can’t look down on someone or something?

Clare looked down and saw something she didn’t like.

Eternal life vs. Heaven, 12 rounds, championship bout, cage match.

*

Big. Black. Ants. Carpenter ants eating their trails through our soft ,wet wood due to roof neglect. Us, my current partner Robin and I. Del (Delphinia) was my first real wife, I liked to tell people, but I’m not going to throw Clare under the bus. She threw herself under the bus.

I’m pausing after that mean thing. Meaner than you think. Suicide. Meaner than that, given various chances to intervene. Del was my excuse to avoid Clare, during and after that marriage. I couldn’t afford another kid. I had my own problems. I had a cutter loose in the house.

Some churches say you’ll go to hell if you commit suicide. They probably say that because otherwise we’d all be killing ourselves to get to heaven sooner, right?

*

One early evening in late April years ago, I was walking alone on a trail in the park across the street—a trail I still walk on after work— working the same job I worked then—”Mr. Handyman,” where I am one of many, not the Mr. Handyman, who signs my checks Ricky Stewart. When I came over the slight rise up from Panther Hollow, I ran into Sid walking the other way with another boy—maybe thirteen, both of them. Looking at them together, I suddenly saw everything clearly: they were looking for a place to have sex in the rising greenery of spring in that large, urban park full of hiding places. Who would’ve thought they’d run into old Dad taking his constitutional? “Hi,” I said, and kept walking, and neither of us said a word to each other or anyone in the family about that ever, but shortly after, he started making those cuts on his arms and legs. I, ex-junkie husband of junkie Clare, never noticed all his long sleeves of summer.

Hey, I used to shoot heroin. At least you’re not doing that. Never do that. Hey, we have something in common, isn’t that cool? I used to shoot up between my toes, can you believe it, ha ha ha. Don’t do that. Stop cutting. Start talking to me. Your mother saved me, but that didn’t save our marriage.

Here’s what I did tell him: We’ll find someone for you to talk to. I was a handyman by default. Something I learned on the fly once I stopped stealing from my own family. Once I dropped Clare off at rehab and drove away forever. Who said talk is cheap?

I was so used to sweeping up, leaving no evidence. It’s never that simple. For example, I did not drive away forever. Forever in my imagination. In my revised version where ants aren’t raining down on me.

*

I was on a first-name basis with the exterminator, Metallica, due to previous encounters with the entire range of invasive urban insects. I even had a customer loyalty card, a 3×5 blank notecard that he’d punch a hole in every time he came out.

Despite spraying with my over-the-counter stuff, the reinforcement ants emerged from wherever the nest was up there, and I gave up and made the call. Metallica clearly does not give a shit about self-poisoning. He wears no protective gear. Lugs around his tank of poison with his gap-toothed smile. I know a lot of people like that, given my personal history. But bug killer doesn’t even get you high.

“Dude,” he said, clanking up the steps, the tank bouncing off his leg. He shook my hand forcefully, perhaps to remind me that we’re in this together somehow. Remember to wash your hand, I tell myself.

“Might want to fix that roof,” he says, peering up at the wet, rotting boards. “Aren’t you the Handyman?”

“I am just one of his minions,” I said.

“You’re one deep motherfucking bullshitter,” he said, spitting his poison saliva over the porch railing for punctuation.

As he sprayed into the holes he’d drilled, the ants came raining down. That’s not just an expression. It was a storm of ants, falling to their deaths, having all looked down.

“Impressive,” I said from behind the screen door.

“You’re gonna need an ant umbrella to come out here,” he said.

I didn’t want to let him into the house. I handed off the check in the doorway.

He smoked as he worked. He had a precision trigger finger on the hose, but his smoking fingers always had a tremble to them.

“It’s not my fault they came back,” he said as he punched my note card again.

*

I never told Robin much about Clare. I told her Del was my first real wife. Clare, Del, then Robin. Don’t mix them up like I have.

When Robin found me crying in the bathtub, she had a few questions:

“I thought she wasn’t a real wife?” Not exactly a question, but a comment that demanded response. I didn’t cry much, but when I did, the bathtub was my go-to spot.

“She had an in with God and got us annulled,” I said.

“I thought that meant you just lived together. What other secrets you got for me, Bathing Beauty,” she said. That wasn’t a question either.

I tore some toilet paper off the roll and blew my nose into it.

“I was high most of the time, so I’m sure I forgot a few things. You’ve never seen me high. Consider yourself lucky.”

“Lucky is not the word for what I’m feeling,” she said. “I’m never jealous about Del. It’s like we’re even—with me and Teddy Boy. Now, you’re one up on me.”

“Not according—” I was going to make a joke about the Pope, but started crying again. I was holding something in, and cutting myself or injecting myself wasn’t going to let it out. Because it was in me—a version of myself I had to own up to and mourn at the same time.

*

I once got up in the middle of the night to pee and found two-year-old Anna sitting in the empty bathtub in the dark.

“Oh, hi Dad,” she said, like I was dropping in on her to borrow a cup of bubbles. She seemed so at home there—to have life be that simple again, sitting in a bathtub in silent darkness. Safe. She knew she was safe there.

*

“Oh, hi Robin,” I said, once I stopped that crazy shivering shoulder thing I get when I’m on a crying jag. Which happens only every time Hailey’s Comet passes by.

*

“We got married on a dare and enough drugs to keep us awake till we got to Vegas.”

“And that lasted exactly how long?”

Robin wasn’t the jealous type. She’d survived her own bad marriage and had no interest in tying the knot again. She was asking more out of curiosity, I hope. She made a good living as a family court judge and didn’t want me suing for support, since my odd jobs resulted in an odd level of income much less than hers.

“We’d lived together for a year or so before getting married, but marriage was the kiss of death and we—well, actually, she—got it annulled. They didn’t have computers back then, but you can see the remnants of our marriage on some erasable typing paper up in the attic with the bishop’s signature and seal.”

“In the eyes of God,” she said. “You weren’t married in the eyes of God.” Robin repeated with an eye roll. She inherited cynicism from her father, an immigrant who had seen bodies stacked up in churches back in Croatia after World War II.

“Isn’t God blind?”

“That’s Justice. And that’s a lie, too.”

Robin had no faith to lose. Clare, on the other hand, found God back in a jail cell, and God told her to dump that loser and get straight, and so, annulment.

“In light of recent events, God wasn’t enough,” Robin said.

I got up out of the empty bathtub, fully clothed. “I hate that phrase, ‘in light of recent events’,” I said.

She looked at me like she was going to respond, her lips briefly parted, to defend that phrase, but we had been together for three years, and she knew that the phrase wasn’t what it was about.

I stormed out onto the front porch to have a little talk with the ants.

*

Clare was 33. Not the 27 club, but the Jesus club. When we die young, suddenly it’s a contest to see who can grieve the most. To possess the death. The ants carry away the dead bodies to be consumed back in their crib up in my rafters. When we die young, it’s like somebody spiked the funeral home Kool-Aid with grief pills. The spiraling wailing, the

random fleeing, the grieving bodies bouncing off walls like the blind, colliding into each other and comingling tears. It’s a swamp of grief, all kinds of shit growing in the fetid waters. The ant-like frenzy in response to poison, the sudden spazzing into death.

Above the ants this humid morning, a hawk drifts effortlessly on breezes we’re not feeling down here. Why don’t we have a more effortless word than “effortlessly”? It stumbles out of our mouths, trips on sidewalk cracks.

*

Clare, who I am mourning later—mourning now—is like the one ant circling the porch after the magic poison is sprayed, as if saying, ‘Hey, where’d you guys go? I’m all alone down here.’ The overeager kid wanting a playmate. Good luck with that, Metallica would say.

*

No, when she killed herself, she was saying, no more playmates for me. I’m blowing this pop(sicle) stand. You can buy that on a mug now. They should put a warning on it: Do not drink poison from this cup.

*

We are all cannibals, of course.

*

Hey, ant, come over here so I can squish you and you can join your friends!

I sweep the dead ones off the porch, and they land on the driveway, little crunchy commas splicing apart complete sentences.

*

The ant carries around the poison powder on its little feet, then slows down. Then stops to think about the meaning of life.

*

If all the ants die, who will be left to eat them? I admire the ants for dragging their dead off the battlefield, even if it is to be their dinner. Get rid of the bodies. Get on with it.

Clare wasn’t young and wasn’t old. She fell and keeps on falling, her mad whisper keeping that hawk aloft.

If we all think hard enough, we all hurt somewhere, right?

*

RICE: Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation.

I sprained my ankle last week, tripping over some a pipe in a bathroom I was fixing. A job I still need to finish, according to a phone message from Mr. Handyman. I’m wearing one of those stupid black medical boots that make you limp.

I’ll be clomping into the funeral. They call them celebrations of life these days, but she wasn’t exactly celebrating life when she took those pills. It’s what her parents are calling it. They, who wanted to know if we lit the Unity Candle at our wedding. We come back from Vegas wearing cheap rings, and that’s what they want to know. Elvis didn’t have one, I said. Didn’t they know we were a couple of pyromaniacs? They knew me from when I was a popsicle boy.

Will they ask me about the ankle? Will they want me to say a few words? Will they speak to me at all, the survivor of sadness, the duke of denial, the king of cocaine, the asshole of AA?

Her next guy—she never married again—called me up when they split to tell me he was going to piss on my grave. Apropos of nothing except having heard some version of our life together. Who was he to say?

“She can piss on my grave,” I told him, “but you can’t. I’d prefer dancing on graves rather than pissing,” I said, “though I realize that from my grave I will have no say in this.”

“Annulled, my ass,” he said, and hung up.

The last thing she said to me was, “Shut up and get a tattoo.” Advice I have tried to take. Tattoo, check. Shutting up, no check. Tattoo of a series of concentric circles on my forearm. A target I once hit without fail. Bullseye!

*

Recovery is not some kind of neat acronym that follows a precise order. Ditto with the stages of grief. But I guess they don’t spell anything to begin with. They can’t even agree on how many stages there are—five? Seven? As if there is ever a final stage: DABDA? SPADTRA? Will all those vowels, they should have been able to come up with something. YABBA DABBA DO!

I’m starting with I:

ICE

The last time we spoke was at a potluck housewarming for our mutual friend Sam. I brought death-machine pie from the supermarket. Too sweet, like always—store-bought pie, what was I thinking? I also brought vanilla ice cream to put on top to make it even more too sweet. I have a sweet tooth. See popsicles above.

Those in recovery usually find each other at gatherings like those. It’s like llamas who smell your breath—you can feel it in the hesitations and discomfort. In the stepping outside for cigarettes. In the fact that they are not holding a brown bottle or stemmed glass. The way they trail their hands through the melting ice in the cooler as if fishing for a miracle to drink.

The way they hold those cheap plastic water bottles that crackle when you squeeze them. The frequency of crackling. The labels floating in the cooler, the cheap glue useless—how quick it can happen, the release of the label. Then anything can happen.

*

For a grown man, I still eat a lot of popsicles. So many flavors these days! Mango! Watermelon! Coconut! Happiness! That kid on the porch stuck with grape, orange, and cherry—and he only liked cherry. And he never got up the nerve to walk across the street to talk to the cute girl on her porch whose nervous twitch he could spot, even from that distance. Not until he started drinking and redefined sweetness into an unpopular flavor that she fled from, only to get pregnant with a football star’s baby. Kid! Kid! Maybe she would have squished some ants with you! Maybe you could have shared how good it feels!

Clare’s parents took care of the baby, as in taking her to Canada to have an abortion. She said he raped her.

He raped her.

*

Okay, Clare was that girl on the porch. Okay, okay. Ice is good for numbing. For a time, I was addicted to cubes. I bit into them and drove Del crazy.

*

We kept some of those plastic Bug’s Life/Antz McHappy Burger King meal giveaways. How do you make an ant smile? Bright lime green ants. Tossed in the blue plastic barrel with the cowboys and army men and thrown away en masse during one of the many purges. Or, maybe they’re in Del’s basement—she had the sentimental gene. The savior gene. But once I was saved, then what? Dullsville, and even giant fluorescent ants couldn’t make life interesting once the kids were teenagers. Even if you stepped on them.

*

Clare brought Downer Salad and ballistic dressing to Sam’s. We made small talk for big kids. Clare. “There’s no I in Clare,” she always told me and everyone else.

“When did you first hear the word “balsamic,”” I asked. “When I was a kid, balsamic was a variation on Greek Orthodox, and nobody I knew was Greek.”

She sighed. “I know I shouldn’t care,” she said. “Why won’t you talk to me?”

“You shouldn’t,” I said. “If I didn’t care, I’d be talking to you.”

“Oh,” she said, “It’s the old, ‘it’s me, not you.’”

“I didn’t say that yet,” I said.

I did not want to admit I couldn’t keep up with her mania—a common path, I know now, from drug addict to religious zealot, from murderer to religious zealot. The Wing and Wang of addiction and belief. She wasn’t going to hold still, even for Jesus. If I died, she would’ve abandoned me on the side of the road, I’d realized, my inability to keep up seriously compromised by death. Then they’d come by and scrape me up and throw me in the back of the truck with the other dead bodies. The Antz, just on a larger scale. And maybe that was okay.

“Are you eating a lot of carrots?” I asked. “Your skin looks orange.”

“It’s called healthy, Rick.” She rolled her eyes. “You were just used to the junkie pallor. I’ve moved way up on the color wheel,” she said. “You still look kind of invisible,” she said. “No offense.”

“I still feel kind of invisible,” I said, feeling one of those old love pangs again, love slivers that never quite get removed. Slivers of slivers dug in deep. “It’s a different invisible. The wife-and-kids invisible.”

“You’re not happy? Wasn’t that one wife ago?”

“Sometimes I miss killing myself. I mean, almost. Isn’t there a middle ground? I could use just a tad more obliviousness.

“I wouldn’t know,” she said. “I’m still an extremist.” She smiled mysteriously.

She was a killer bee, and in lieu of having someone to sting, she stung herself. I didn’t see it coming, mistaking her energy for invincibility.

*

“It’s good to see you two talking,” Sam said.

“Why’s that?” I asked.

“Yeah, why?” she asked.

We exchanged The Smile. Capital T Capital S.

This smile that said I don’t really want to smile, but I just can’t help it. The smile I had for no one else.

REST

My leg tensed on the chair she once sat in. The porch chair that survived her and Del and moved with me to Robin. Clare did not have a favorite chair. I was going to say that she did, but she didn’t. She’d sit anywhere. She was one of those people who preferred the floor. Wrought iron—new cushions, but the same frame. Overwrought iron—the same joke I used with all of them at various points.

My ankle only hurts when I laugh, so I am not laughing. I am resting. I don’t want to go to the funeral. Just like I did not want to answer her phone calls and texts. I wasn’t going to mention them—a little secret from Del and Robin—Clare had in recent weeks been buzzing on my phone and sending cryptic texts like “Howdy Sailor” and not so cryptic like “Call me, you asshole I don’t bit.” She forgot or erased the e.

I was thinking about cutting and pasting some of her texts in here, but it turns out I deleted them all, though I saved some emails from

BEFORE. The peppy, jazzy, funny ones that charmed me. Swept me off my feet like an ant swept off the porch. But then it turns out (the double turn out!) that I have some of them memorized. Random observations like “the wind is as crisp as a hairy coconut today” or “Is your second toe still bigger than your first toe?”

*

At first, it’s just the little ants, but they get killed off and the big ants show up. Not big enough to eat me, but still pretty big compared to the little ones. The little ones are almost a concept, an abstraction. Tiny punctuation you can almost ignore. They dutifully enter ant traps until you can shake them like maracas.

Did I spill something to attract the big ants? I did not. The big ants, they say, you talkin’ to me? I ain’t going in that dark little trap, chump! Gimme some wet wood pronto!

VICE

One of the two stages of life.

a metal tool with movable jaws that are used to hold an object firmly in place while work is done on it, typically attached to a workbench.

*

She wanted to be swept off the porch, not buried in a box, but I had no official role as the annullee. I was just an attendee.

I’m glad I did not join her in ant land—addicted to poison. But her electric madness shorts me out with grief. Two children on identical shy slabs of cement ran away from the ants only to swallow the poison themselves. How do you warm a house? Not with explosives. Not with spilled blood from precise cuts.

Del called me to inform me of Clare’s death. She thought I’d want to know. Tomorrow I will join the ants on the freeway to the funeral. She’d been living on an organic farm outside of town where all the workers had tattoos that they covered up for their fancy farm-to-table dinners. Some kind of cult, though we’re all in some kind of cult, even if it’s a cult of one. How long will the receiving line be? Not very, I’m guessing. Unless it’s at the methadone clinic.

When my father died, he’d outlived all his friends except for Lenny in Arizona who had given up driving and lived in a retirement home. I was told to call Lenny, a former ice cream novelties salesman from our old neighborhood in Detroit. “I’m the last one,” Lenny said. With a note of triumph, or resignation? I wanted to ask, but his lunch was being served. He complained about the paper cups of ice cream they served. “Not ice cream at all,” he said. “Some fake over-frozen vanilla stuff with the cheap wooden spoon that can’t put a dent in it. They think we’ll hurt ourselves if we had real spoons. Whoever hurt themself with a spoon?” Lenny was a Bombpop afficionado who did not believe in the simple, the colorless, the bland. In truth, my father did not like talking to Lenny in Arizona. My father was not a talker like the ice cream salesman.

“He could sell ice cream to Eskimos,” my father said.

“You can’t call them Eskimos anymore,” I said.

My father made our children shake hands with him. No hugging or kissing. No “I love you’s.” This isn’t an excuse. He believed in a firm grip, and it got him through. We all have to figure that out on our own, not just do what our parents do.

“Lenny, the Bomb pop had a fatal flaw,” I told him. “You couldn’t get the whole damn thing in your mouth, so it dripped all over your hand.”

“Ralph,” he called me, which was my father’s name. “You got a small mouth. You’re full of shit, just like always.”

*

Then the flies start showing up, then the wasps. I have never seen a movie about cute flies on a dung pile, or wasps in their paper nests, but bees get a pass, due to honey.

What’s an occasional sting if it means honey in the long run? A conundrum of addiction.

Maybe I should stop being such a smartass. That’s the kind of logic that can turn you into a junkie. Clare, nodding off, sprawled in a slumped, insubstantial pose. Human lumps of clay we were, unwilling to be molded into purpose except to obtain more.

*

Wasp spray shoots up to twenty feet. Or the distance from heaven to earth. The wasps crawl out of their nests like junkies after a bust, then tumble to earth to twitch briefly and die. Maybe I don’t have to tell you, but I enjoy blasting wasp spray across the driveway into the eaves of the garage, safe in the killing.

*

Life is an ant trap. Safe in the killing.

*

ICE

Nobody move.

Cheap crinkly water bottle swimming in it.

*

ORTHO. RAID. ROUNDUP. HOME DEFENSE. REAL KILL. DIAZINON. DEET. CUTTER. COMBAT MAX with Accushot sprayer. CAPTAIN JACK’S DEADBUG BREW. HOT SHOT with Egg Kill! BUG STO(M)P.

*

Her parents sent out bounty hunters to find a minister to do the service. Where’s Elvis when you need him?

*

Del, sympathetic on the phone, wasn’t coming all the way from Houston. She was living with Tom, a friend of both of ours from way back— high school, maybe further. Tom helped her move her stuff out of the house then took her down to Houston to start over. With my kids. What a pal, Tom. They knew Clare from their bowling league. In Detroit, everybody bowls. Church groups, methadone clinics, ice cream salesmen.

Life is full of fallback positions, but we need to get through the first thirty years or so before we have enough of them lined up behind us. Like that fun game where you fall backward and trust someone to catch you. You need a bunch of people back there to increase the odds of somebody stepping up. Some of them are just going to let you fall. Who let Clare fall, finally? Or, who did Clare feel she could finally trust to let herself fall? She was sending out her SOS texts, and I was killing ants on the porch, afraid to step across the street again.

Yes, I let her fall—I’m on the list. I thought she was going to tie her shoe then get up again. I blame it on the naivety pills the doctor has me on. I blame it on me, but that’s our little secret. I have an emergency appointment scheduled after the funeral with the pill doctor.

I need to go to prove to myself that I did not abandon her. That she abandoned me, then circled back, thinking I’d still be there. But then I had kids to take to ant movies and then superhero movies and then teen rom-com movies. Somebody has to buy the popcorn, which reminds me:

RICE

Ice it. Ice it or heat it, the eternal debate. Obviously, I made the wrong choice.

The science behind RICE had never been tested. Everybody just likes the mnemonic device. Hell, it took me forever just to learn how to spell mnemonic. Just how many words have an m and n together at the beginning like that?

If ants had dog tags, this battlefield would sparkle with their deaths. Tiny pieces of Safe-T-Glass around their necks.

ICE

The brief pleasure of numbness to calm the tissue. To begin healing.

COMPRESSION

Clare and I, we compressed ourselves together and for a brief time healed each other or distracted each other or sweat and slid against each other as if we could live forever without effort. Without lessly.

Lost in the weeds. I like getting lost in the weeds, hidden in greenery. By greenery. Surrounded by it, off the main road, the uncultivated and wild sprawl. The drugs were hidden there. Lotz of bugz in those weeds too.

I’d put myself in the vice in the first place. Vice—all those definitions squeezed together.

*

BUGZ LIFE VS. ANTS

I wanted to carry that Z with me everywhere, the simple joy of my kids holding my hands in the dark, but that was just another illusion/ mirage/shadow puppet of God.

I know I am repeating myself. At least I’m not in the bathtub anymore. Am I at the funeral yet? Did anyone eat my store-bought pie?

The funeral—no, I’m skipping it. It never happened or didn’t happen yet or is happening as I speak. She didn’t want a funeral. Her parents were extremely helpful with the annulment, if you know what I mean, so I wasn’t looking forward to seeing them see me, that roughly erased patch in their dead girl’s life.

What am I saying? They’re not going to care about me paying my respects. They’d taken my respects a long, long time ago. To hell with respects, I’d be thinking if I was them. I was thinking it myself. It was hollowing out my chest, even if I was partly grieving for myself. Maybe that’s what Robin knew in that bathroom. I wasn’t heaving my chest like that and stuttering grief for lost love. And not to show off, exaggerate the grief like in that funeral home whose floor was electrified with it. No, it was for me.

*

Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. In a borrowed urn, they sit. It looks like Jesus was still hanging around until the end. I don’t know what kind of story she told him before she said her goodbyes. A crucifix—

*

The flies are crawling now, and the ants are flying. How did we end up here?

Once when Del and I were still married, we flew to France to renew our vows.

Don’t ever renew your vows. It’s almost as stupid as throwing a baggy full of speed in the car and driving to Las Vegas to get married.

Del and I did not get married by an Elvis Impersonator.

Once, a swarm of bees took up residence between the shutter and window in our garage. We called a beekeeper, who was glad to take them away so they could make honey for him. One person’s pest is another person’s…pest. Who can I call to take away the ant colony?

I keep thinking we should have found a way to live with the bees, who had no interest in us. I should have found a way.

*

Clare made a death play list, and it was not the sound of bees buzzing.

I might put bees on mine if I leave the world behind on my own terms like she did. I can’t say I won’t. But I want to say it.

I don’t know what’s on her playlist. Sam heard about it from her parents. They trust Sam.

*

Music has its limitations, though I have been a fan of Wishful Thinking. I have all their albums. I like the warped vinyl of my youth the best. I like when it skips, when it goes back, then forward again.

Sam and his current partner Jan made Coma Playlists, imagining what songs might bring them out of one. They are co-presidents of the Wishful Thinking fan club. Jan admits to sleeping with their lead singer back in her wild days.

*

In France, the designated driver is named Sam. Del and I had some good meals there before we came home and got divorced. Sam I Am until the end of my days.

*

Ants tremble in their death throes. Are there any other kind of throes?

I used to be able to catch flies in my hands. Also, a wasp stung me when I opened the empty mailbox when we got home from France. When you leave, there’s always someone else moving in. Nature abhors a vacuum, Aristotle supposedly said, and that was before the invention of vacuum cleaners. Before the abandonment of the word abhors.

*

I miss the beehive. The sweet dripping buzz.

Ant traps, roach motels, mosquito condos, pigeon high-rises of death. Human fireball death traps. Oh, to go out like a human fireball. Without the pain, I mean. Is life a beehive or ant trap? Do we “check in but never check out” like the commercials say?

I took the wrought iron chair. Clare took a poster of a cat saying Hang in There. The chairs come in pairs. I stole one and left the other one.

Don’t make a mountain out of a mole hill or a pile of beans out of an ant hill.

Everything stings.